Share this story

As an educator and veteran high school English teacher, I am passionate about literacy. In fact, that passion is why I chose education as my life’s work.

As educators and as parents, we know first-hand how vital the first few years of a child’s education are, and that learning to read is essential to academic progress and success. We instinctively know that learning to read is an important milestone in a child’s life, and that development of a habit of reading can transform a person’s entire life. It is the foundation of an education, which in turn can enable a child who begins in the most modest circumstances to climb the ladders of prosperity in their social, economic, and spiritual spheres.

Formal research has confirmed these claims. Teaching a child how to read prior to third grade is the number one indicator of success throughout the rest of that child’s life. A study by the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that students who were not proficient in reading by the end of third grade were four times more likely to drop out of high school than proficient readers.

Unfortunately, throughout North Carolina and the entire United States, too many of our children enter high school unable to read proficiently, ultimately jeopardizing their chances of postsecondary success. Even before the pandemic, only 43 percent of third graders in our state demonstrated grade-level reading proficiency. Despite a heroic army of teachers and administrators, our institutions were failing in their most important task.

My primary objective since taking office on January 1, 2021, has been to raise the quality of education in our state for all learners. From day one, my team identified early literacy as a critical strategy to achieving this objective.

Many readers of this article may be surprised to learn that the generation before or after was taught reading in a fundamentally different manner. Until the 1930s, the prevailing method of teaching reading throughout the United States was based on an approach generally described as “phonics”– the sounding out of letters. Encouraged by certain prominent and well-meaning schools of education as well as state education boards, phonics’ grasp was chipped away at the district and state levels for several decades by a rival technique known as “whole language instruction.” By the mid-1980s, whole language instruction (WLI) had become the dominant method of reading instruction. For example, California adopted a statewide WLI mandate in 1987. Within seven years, California reading proficiency scores dropped to second-to-last in the United States — behind only one state, Mississippi.

In North Carolina, decisions on the technique to use to teach reading have traditionally been made at the county, school, and sometimes even the classroom level.

In the spring of 2021, I joined education leaders, thought partners, and policymakers in leveraging the results of ample scientific research to guide a better approach to teaching reading in our schools. Our agency worked closely with the North Carolina Senate to help develop legislation to provide foundational professional development to educators in evidence-based methods of literacy instruction.

This effort culminated in the passage of Senate Bill 387, the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021. The act passed the North Carolina Senate unanimously (48-0) and the House (113-5) and was signed into law by the Governor a week later.

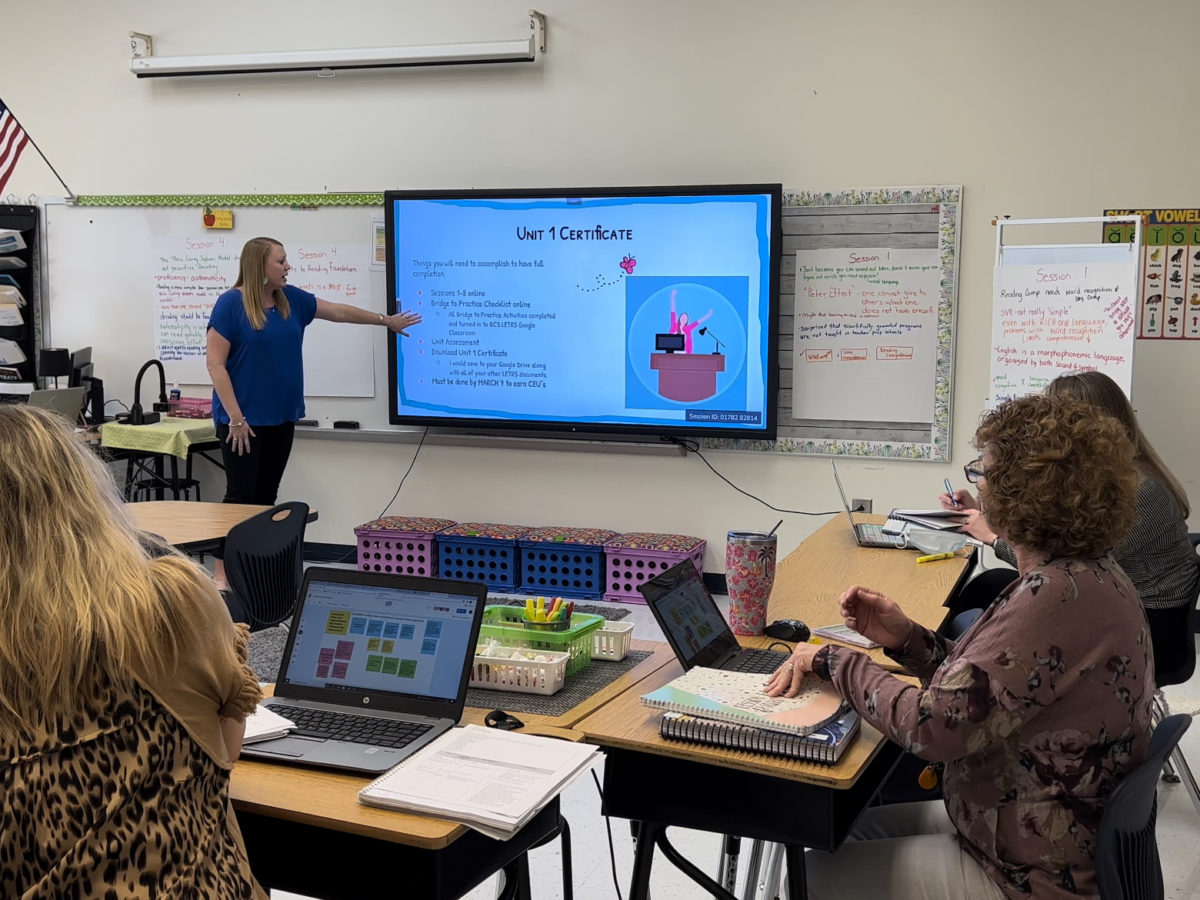

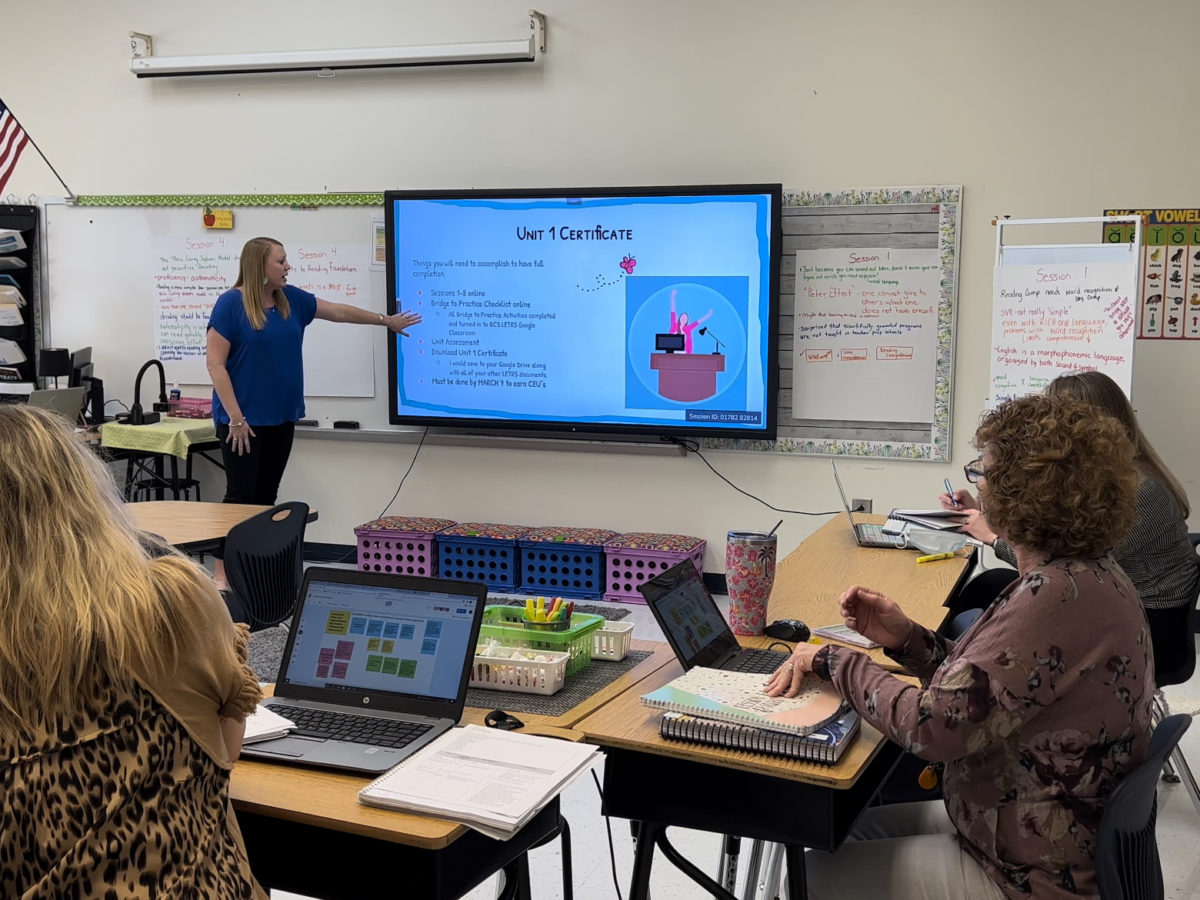

Specifically, the act named a specific vendor, LETRS (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling), as the professional development provider for every pre-K through 5th grade teacher in our state, including one administrator per elementary school. Securing this professional development for all elementary teachers, including teachers for Exceptional Children (EC) and Multilingual Learners (MLs), meant that all teachers would receive the same high-quality training and hands-on support regardless of zip code. LETRS was selected due to its success in revolutionizing literacy instruction in, you guessed it, Mississippi — which witnessed substantial gains after implementation of the program in 2014. The professional development requires a substantial time commitment by participants.

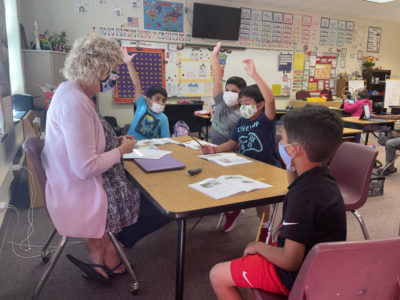

With an established program and funding from both the state and federal COVID relief dollars, our agency kicked off this transformational journey last fall when North Carolina’s 115 school districts were placed into LETRS cohorts with staggered start dates. But while we were incredibly excited to get this work off the ground, we had to remind ourselves that teachers were already exhausted from the pandemic and its litany of collateral effects. Teachers were unlikely to be excited by the prospect of adding to their existing workload an intense professional development course spanning two years. In response, the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) set up a process to receive honest feedback from the field. And while there was pushback from some at the outset, as time went on, we began to see a change of heart.

“At the beginning of implementation, I thought that LETRS was a lot of work but now I see that it is a lot of meaningful work,” said a participant from Bladen County Schools. A similar sentiment was echoed by Northampton County Schools, stating that “Teachers used to think this was just another thing to have to do but now they are saying they see how the training has impacted student learning and now they see the alignment to what we’re doing.”

As the third and final cohort of teachers began their LETRS experience this summer, our agency started work on a robust and statewide coaching model critical to sustaining this work long-term. The support model is comprehensive and thorough. It includes attaching a literacy facilitator to each of the eight education regions who will ensure LETRS training continues for teachers new to North Carolina. It also provides one early literacy specialist who serves as a collaborative partner between NCDPI and each district, providing district and school level coaching, support, and feedback.

Encouraging statewide adoption of a phonics-based literacy model constitutes a monumental commitment of time, budgetary resources, and bandwidth. Nearly 26,000 educators participated in LETRS training in 2021-22, and this fall we’ll have 57 districts joining to bring the total to 44,035 educators participating in LETRS professional development. Having studied the research prior to embarking on this project, I am supremely confident that these investments will pay rich dividends to our ultimate constituents — our schoolchildren.

According to data provided by Amplify, this year’s first graders began school with a 38% reading proficiency rate, but by the end of the school year they had reached an incredible 63% proficiency rate. In fact, preliminary data from North Carolina kindergarten through second grade students’ end-of-year reading assessment show that our students are growing faster than the rest of the nation. While we are only one year into this work, I know there are more promising outcomes on the horizon.

As I reflect on this first year anniversary of professional development implemented in the field, I continue to be amazed and inspired by our elementary school teachers. I applaud their tenacity in learning new skills and mastering old ones, and I can’t wait to see how their work continues to benefit North Carolina’s students for decades to come.