One North Carolina program is helping beginning teachers in the state’s public schools get the help and support they need to be successful in the classroom and persist in their new careers.

Working in the state’s high-priority schools, The North Carolina New Teacher Support Program assists teachers in the first three years of their career by pairing them with an instructional coach, an experienced teacher who acts as a mentor and partner, offering advice, guidance, and, frequently, a sympathetic ear.

Born out of North Carolina’s Race to the Top grant, the New Teacher Support Program was created to address high-rates of teacher turnover and low retention in the state’s high-need schools, institutions that typically have more new teachers, lateral-entry teachers, and teachers trained out-of-state.

Data shows that improving teacher quality and retention is key to reducing educational achievement gaps. The program notes on its website that students with high-quality teachers have the equivalent of an extra 100 days of instructional time. The program’s cost-sharing plan means participating schools and districts pay only $1,900 for each participating teacher. Teachers continue to receive coaching and support through the first three years of their career.

For many districts, it’s a small price to pay to retain quality teachers, offsetting the nearly $84 million dollars a year the state loses through teacher attrition.

In 2014, the program transitioned from Race to the Top funds to funding from a variety of sources, including the State of North Carolina, the University of North Carolina, GEAR UP NC, and various charitable foundations.

EdNC recently visited one of the schools where the program is actively involved. Rochelle Middle School in Kinston is a high-priority school, with 100 percent of its students on the free- and reduced-priced-lunch plan. It has a 96 percent minority enrollment and more than 80 percent of its nearly 500 students are considered economically disadvantaged. It has a 20 percent teacher turnover rate and 43 percent of the school’s teachers have only zero-to-three years of experience.

And it just received a letter grade of F in the most recent round of school report cards.

Rochelle Middle School Assistant Principal Andre Whitfield understands the many challenges facing his school and the teachers who work there, but he’s also very aware of the many difficulties his students face everyday outside the classroom.

“A lot of our students come from an area where there’s high crime rates and they are at risk of gang-infused neighborhoods,” said Whitfield. “They bring those challenges from the community into the schools. So a lot of time we are dealing with those types of situations.”

Watch the video below to hear more about Rochelle Middle School.

https://youtu.be/VgmQ9a8zhSQ

Many of the schools served by the New Teacher Support Program have similar stories to Rochelle’s. Communities where students must navigate the daily demands of school with the harsh realities of life outside the classroom walls. It is a demanding job for even the most experienced teachers. For new teachers, who are just starting out, it can end a career.

That’s where the coaches come in. For Morgan Dixon, a first-year teacher in the program and a seventh- and eighth-grade science teacher at Contentnea-Savannah K-8 School in Lenoir County, the advice and support provided by her coach, April Shackleford, has been critical in her first-year as a lateral entry teacher.

Watch the video below to hear Dixon talk about working with her instructional coach.

https://youtu.be/v3hXvTZkdFk

Though the instructional coaches are often life-lines to the new teachers, it’s clear when they speak that they themselves view the relationships more like a partnership, working in tandem with the new teacher to find the solutions and practices that best fit them and the students in their classrooms.

“They don’t give themselves enough credit,” said Shackleford, who is also the instructional coach for Nichole Hathaway, a sixth-grade science teacher who is also in her first year at Contentnea-Savannah K-8 School. “Even though they don’t have the traditional teacher training, they are able to sit at the table with me and tell me what they need and what they don’t need.”

“We have developed a relationship where they will say, ‘That is a beautiful idea, but I don’t think I’m ready for that right now,'” Shackleford continued. “And they don’t look for a prescription when I come in, they know that I am just going to put out fires. Like if I see a kid misbehaving, I am going to come in and sit with that kid, long enough for them to teach a 40-minute lesson.”

But Shackelford knows she and her fellow coaches can provide an experienced viewpoint to new teachers that they may not be able to get elsewhere. Specifically, she cites the increasing focus on analyzing student testing data to measure student performance and teacher effectiveness.

According to Shackleford, what the New Teacher Support Program provides is a resource for new teachers to think beyond the data and get feedback on how to improve outcomes for struggling students.

“The challenges I am seeing with our beginning teachers, most of the planning meetings they are having is dealing with data, not true curriculum and instructional strategies,” said Shackleford. “So they assess their kids over and over again, then they get the data back of what the kids performances are, but they aren’t always given the tools and the strategies to fix the problem.”

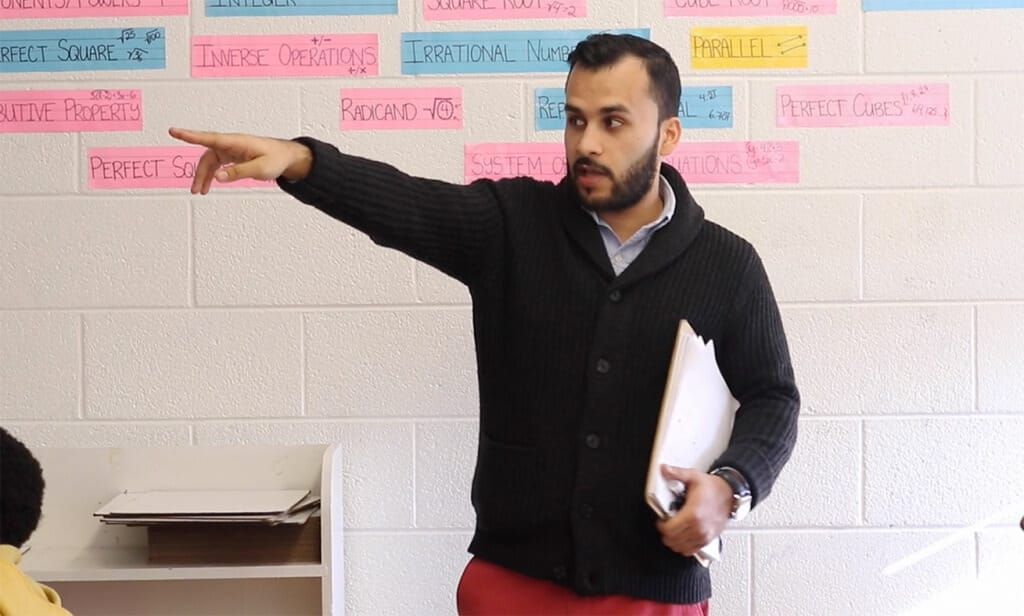

For second-year teacher Dorian Edwards, a seventh-grade math teacher at Rochelle Middle School, the New Teacher Support Program has helped ease his transition as a lateral-entry teacher. Edwards never intended to go into teaching, but a summer experience working at a nearby camp made him realize his passion for working with youth. It also brought him back to his hometown of Kinston and to the very middle school he attended as a child.

Watch the video below to hear more about Dorian’s story.

https://youtu.be/w27PZ4t2HCA

For Edwards, the support of Instructional Coach Felita Gilliam has helped him find his own voice as a teacher.

“They look at you. They come into your classroom. They see how you operate and give you support based on how you are in your classroom,” said Edwards. “So it’s not necessarily changing what you do but more so enhancing it. Not reinventing the wheel, just making it a little bit more fuel efficient.”

https://youtu.be/LrE-grQ1TKE

For first-year English teacher Darice Harris having an experienced educator like Gilliam at hand as a coach has made the transition into her second career at Rochelle Middle School much smoother.

“Having her here has been fantastic,” said Harris, a sixth-grade English teacher. “We were talking yesterday, and I mentioned I was excited about the possibility of using interactive notebooks and that I wanted to start something like that after the holiday break. And because we were discussing it, and because she had resources for me, she emailed stuff right then and there. And then she offered to help me create it [the curriculum] in different ways so it isn’t completely thrown at the students all brand new.”

Lateral-entry teachers like Harris comprise a significant portion of the teachers working in North Carolina’s high-priority schools. Across the state, those teachers accounted for 20 percent of all first-year teachers between the school years 2005-06 and 2011-12. Those second-career teachers are critical for providing high-quality educators in the state’s rural communities

“Eastern North Carolina feels the true impact of the teacher shortage, especially in rural areas,” said Ann Bullock, a chairperson and associate professor in the Department of Elementary Education and Middle Grades Education at East Carolina University and a regional director in the New Teacher Support Program. “While all schools would like to hire traditionally-prepared teachers, lateral-entry teachers fill a huge void in teacher recruitment and retention in the region. Without the state policies that allow districts to hire teachers via the lateral-entry route, there would be many classrooms without a teacher in eastern North Carolina.”

Watch the video below to hear lateral-entry teacher Nichole Hathaway reflect on her first year of teaching.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zvb7hJIg-dM

First-year teachers like Dixon and Hathaway face unique challenges transitioning into the classroom from other professions, especially into the high-priority schools typically served by the New Teacher Support Program. But the unique situation of teacher and student both learning in real time often results in shared moments that are reminders of why they entered the profession in the first place.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WsdRET569qU

As a veteran teacher and administrator, Rochelle Middle School Assistant Principal Andre Whitfield understands the need to connect new teachers with veteran colleagues. Whitfield himself entered the teaching profession through lateral entry after he left the Navy. The transition from a structured military environment to a chaotic classroom managing distracted young adults almost proved too much for Whitfield in the beginning, but through the support of his veteran colleagues, he persisted and now is trying to provide the same support for the new teachers at Rochelle.

https://youtu.be/PdfSdBH1lTo

Despite the many challenges of being a first-year teacher in a high-priority school, most of the new educators still feel strongly about their decision to embark on their new careers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oeNuZNnNCJs

Recommended reading