The North Carolina Farm Bureau brought its Ag in the Classroom program to Kenansville Elementary School in Duplin County last month, hosting a professional development workshop for elementary- and middle-school teachers on how to incorporate agricultural-themed projects into their classrooms and daily curriculum.

The 30-year-old Ag in the Classroom program is structured to enhance classroom teaching, providing students and teachers with exposure to agriculture and increasing student awareness about the state’s top industry and how the food they eat gets to their plate.

“This is a vehicle that you can incorporate into your objectives, lesson plans, everything you have to teach, whether it’s language arts, math, science, or whatever,” said Michele Reedy, the North Carolina Farm Bureau’s director of Ag in the Classroom.

“If you are in third grade and you have to teach life cycle, why not teach the life cycle of a sweet potato or the life cycle of a chicken?,” Reedy asked the group of Duplin County teachers. “Those are two top-ten commodities in this state, and in this county. So why not teach that to your children? Something they see everyday.”

Agriculture is “an industry that touches everybody,” said Reedy.

Erica Edwards, a teacher at Kenansville Elementary and the organizer of the workshop, had past experience with the Ag in the Classroom program. The experience led her to pursue a doctorate in education, focusing on the integration of agriculture into the classroom curriculum and helping connect more students to their food source.

“Our kids are so far disconnected from the farm,” said Edwards. “Most of our generation today is three or four generations removed [from the farm], and they are not aware of the importance of agriculture.”

History of Ag in the Classroom

A national program, Ag in the Classroom is supported in this state by the Farm Bureau. Launched here in 1985, the program was initially a set curriculum that was distributed to every classroom in North Carolina, according to Reedy. Then in 1990, the program hosted its first professional development event for teachers.

Since then, the program has expanded to include such things as a “Going Local” grant, a Book of the Month program, Ag Science Nights, Going Local Teacher Workshops (which are held at local farms), and ongoing professional development.

“The curriculum is researched based and includes the state Common Core and Essential Standards,” said Reedy. “Each lesson plan is written to be ready-made for teachers to use in the classroom. We strive to provide curricula that is not an addition but one that includes the objectives and standards mandated by the Department of Public Instruction.”

Educators educating the educators

At Kenansville Elementary, Reedy was joined by four specialists, teachers from around the state who had been using Ag in the Classroom in their own schools.

According to Reedy, having teachers guide the workshops and lead the participants through the experiments was crucial. It lends credibility to the message, and the teachers hear firsthand from fellow practitioners on what has worked in their own classroom.

Each group was sorted by grade level and assigned to one of the Ag in the Classroom Curriculum Specialists.

JoJo Nichols, a teacher and language arts specialist from Gates County, worked with the K-1 teachers in attendance, leading them through projects based around corn, including experiments that involved using model corn stalks to teach measurements and an experiment with corn kernels involving vinegar, baking soda, and water.

The solution causes kernels to bob up and down in the jar, like popcorn popping, and helps teach concepts of measurement and proportions to young learners.

Darlene Petranick, a teacher in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools and a former national Ag in the Classroom Teacher of the Year, showed the 2nd-grade teachers exercises to teach students about life cycles and genetics based on the science of poultry farming.

The 3rd-grade teachers learned about the science of soil samples and the life of a vegetable from seedling to harvest with Frances Baker, a teacher and AIG specialist from Nash County. Baker presented the study of seeds and soil as a jumping off point to spark class discussions and student reflections in the subject areas of math and language arts.

“The more you can get the kids to interact with each other, and talk to each other about the text … the better they are about going back and finding the answers and listening to each other,” said Baker.

“A lot of time we [teachers] get hung up asking questions and we don’t give the students time to ask questions.”

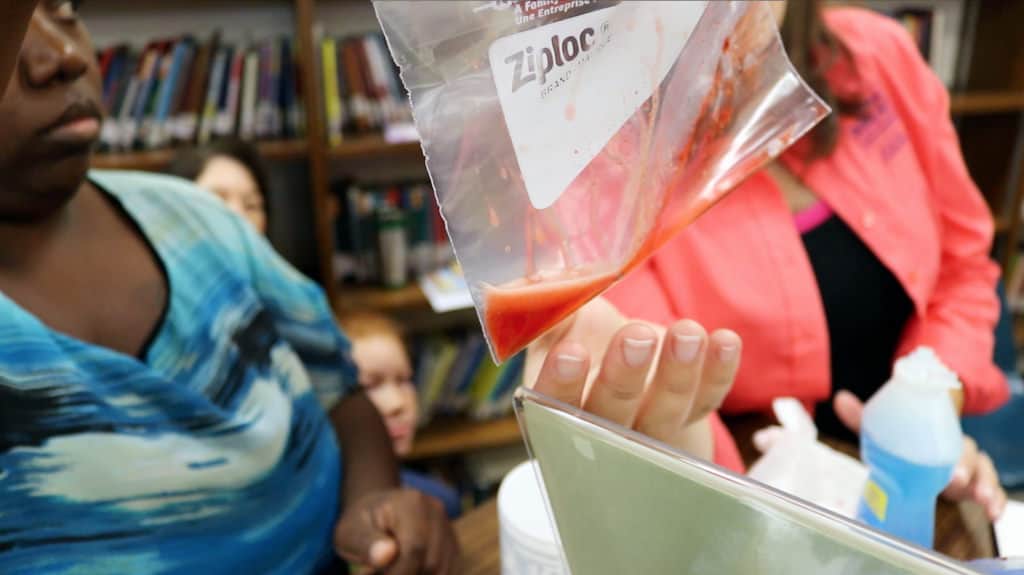

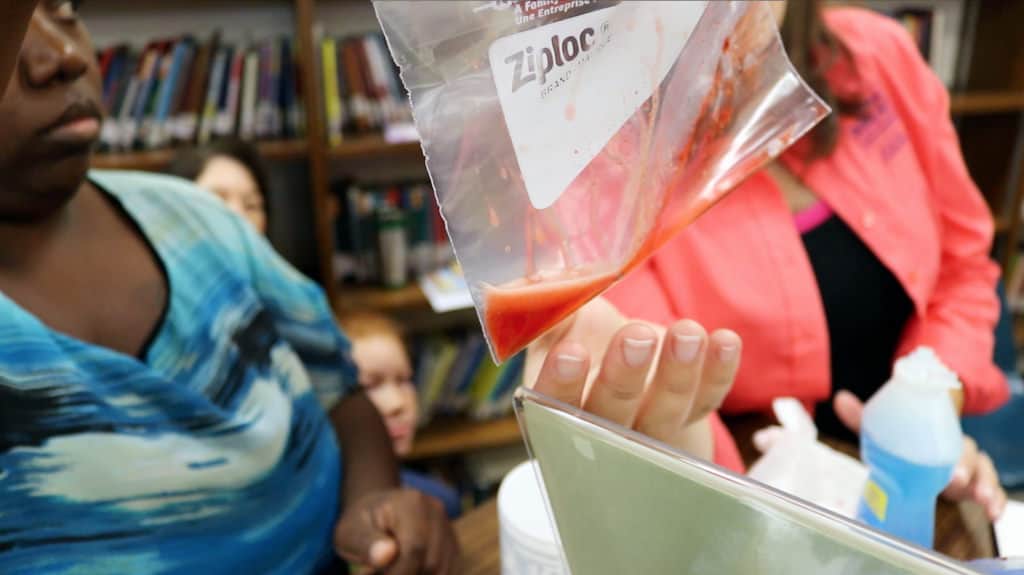

Kenan Fellow Natosha Newton, a teacher in the Iredell-Statesville Schools, guided the 4th- through 8th-grade teachers in an experiment extracting DNA from strawberries.

Newton also gave a presentation on how social media platforms and technology could be incorporated into ag-related projects in their classrooms, using the Ag in the Classroom Book of the Month Esperanza Rising, a novel about a young girl’s life as part of a family of migrant farm workers. Newton showed the group how teachers can meet Common Core text complexity standards by incorporating an ag-related text and promoting discussion and reflection using blogs.

Watch some clips from the experiment and hear from Newton about incorporating technology into the classroom in the video below.

Connecting agricluture and STEM

Whether it was extracting strawberry DNA or incorporating poultry farming into a study of genetics, the overall theme of the day was showing teachers ways to promote STEM in their classrooms using agriculture, helping their students make the mental connection between what they need to learn for the next generation of jobs and how it relates to what is growing in the field next door.

Agriculture incorporates aspects of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) to produce food, fiber, and forestry products. For teachers, it’s a way to connect with students on an issue directly affecting their daily lives while also incorporating real-world applications of STEM concepts.

Natosha Newton relayed the story of an initially skeptical colleague, who after seeing the improvement in the test scores of Newton’s students, asked if she could participate in the program so she could start to incorporate the concepts into her own math class.

“All we are doing [with Ag in the Classroom] is engaging kids in STEM activities, like you saw today,” said Newton. “It changes the game.”

Reedy said STEM fields lend themselves to “teaching by product-design,” empowering students to “take charge of their own learning.”

“Students enjoy learning in an environment where they are given ownership for producing a product such as growing lettuce in an aquatic-based environment,” said Reedy. “They have control of their learning by applying their knowledge to the application process. Their hands work in unison with their ideas and creations through the use of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics to improve the industry of growing their own food. The end result becomes STEAM rather than STEM.”

Duplin County Schools Superintendent Dr. Austin Obasohan was on hand to observe the breakout sessions. Obasohan said programs like Ag in the Classroom were critical for exposing STEM concepts to students in rural counties rich in agriculture, like Duplin.

“The positions that are going to be available in the next 10-15 years are going to be in the STEM field,” said Obasohan. “And agriculture is one of the biggest ones.”

“We want to be ahead of every other school system, every other state, in terms of actually giving our students the first hand knowledge of the STEM fields and how they can better themselves … and have a life career,” said Obasohan.

Hear more of Dr. Obasohan’s comments about the Ag in the Classroom program.

Though programs like Ag in the Classroom are important for introducing students to STEM concepts, they also prepare the next generation to tackle the critical environmental issues facing our planet.

How do you feed more people with less and less arable land?

“As our world is expanding in population and sprawl is taking up more and more rural land, the problem becomes one of sustainability,” said Reedy. “How will our future grow more food, produce more fiber, and grow more trees if our land availability is decreasing? There is a need and a necessity to solve this problem and agriculture is the industry that is readily called upon to find a solution.”