Share this story

- The short session starts Wednesday, and lawmakers are sitting on billions of unanticipated revenue dollars. How might they spend it? What does the governor want to see in a budget? And what else might happen in the short session? #ncpol #nced

- During the short session, the legislature has the option to revive bills that didn’t pass last year and make changes to the budget. Here’s what you need to know. #ncpol #nced

Like clockwork, a long session of the General Assembly is followed by the short, but what does that even mean? And, most importantly, what is North Carolina going to spend its money on in 2022-23?

We’re here with your short session preview of all things K-12, early childhood, and community college. We’ll get into it, but first, where did we leave off?

Background

What happened during the long session?

Any context for the short session budget requires some understanding of what happened with the long session budget. An agreement on that budget was reached in November 2021 — five months after the end of the fiscal year, when the state actually wants to have a new budget in place.

Cooper vetoed the previous budget in 2019, and Republican General Assembly leaders didn’t have the votes to overturn him. So, the budget passed in November 2021 was the first in several years. Also, going into the long session, the state had a surplus of $4 billion, which grew to more than $9 billion in unreserved funds by October 2021.

Because there had been no budget in several years, Republican leaders agreed to negotiate with Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper over what was to be in the budget. That may sound like a reasonable state of affairs, but in North Carolina it’s anything but. In recent years, the governor has generally been shut out of budget negotiations, and that’s even more true since Cooper took office after the tenure of Republican Gov. Pat McCrory.

Ultimately, negotiations between Cooper and legislative leaders fell apart last year, but had advanced far enough that Cooper got enough of what he wanted and ultimately signed the budget. Here are some of the highlights:

- Average 5% increase in teacher pay

- 5% across-the-board pay raises for both principals and community college personnel

- Bonuses for state employees and teachers

- $100 million in funds to provide local supplements to teachers

- Hold harmless provision that prevented districts from losing funding if their student population dropped

- $360 million in COVID-19 federal aid allocations

- $30 million in new funding for the Opportunity Scholarship Program

Check out our overview of the long session budget here.

What’s eligible during the short session?

The short session is different from the long session in that there are limits to what lawmakers can consider. This document lays out what those limits are, but let’s go through some of them.

Bills related to or affecting the budget can be taken up. Basically, the biennium budget included funding that covers two fiscal years: 2021-22 and 2022-23. During the short session, revisions can be made to that second fiscal year because the state has a better handle on revenues and how much money is actually available.

Beyond the budget, a big thing to consider is that any bill that passed at least one chamber during the long session is open for consideration, as are any bills that were vetoed by Cooper.

Wait, so that means…

That’s right. That means we could see another appearance of the bill that would have forced schools and districts to make available to the public information on what instructional materials and activities are being used in classrooms. It passed the House but wasn’t really ever taken up in the Senate.

Also possibly up for consideration is controversial legislation that many took to calling a “critical race theory” bill, even though nothing in the bill explicitly addressed critical race theory or called it that. The bill that ultimately passed the legislature included various concepts that teachers weren’t allowed to “promote.” Cooper vetoed the bill, but the legislature never tried to overturn his veto.

How does the budget roll out?

And that brings us, finally, to second year revisions to the biennium budget. But first, consider the process: The governor releases his proposed budget first and then the Senate and the House take turns presenting their proposals depending on the year.

In the long session, the Senate went first, so this year, the House will kick things off.

Earlier this month, Cooper released his priorities. Next, we can expect the House to present its plan and then the Senate. The Senate and House will haggle over differences and arrive at a final budget proposal, which will likely pass the legislature and go to Cooper for consideration.

But what can we expect to be in this budget? We’re almost there, but first we need to know…

How much money do we have?

A lot.

A consensus revenue forecast dropped recently, and according to it the state will have a roughly $4 billion surplus for the current fiscal year and almost $2 billion for the next one. That’s one-time money, which can’t really be used for recurring expenses, but it does give lawmakers and the governor some wiggle room.

Lawmakers have indicated their plan when it comes to these dollars.

“It is crucial that we continue on this track of responsible and disciplined spending in light of the potential for a recession as we begin the short session budget process,” said House Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, and Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, in a statement.

Cooper himself doesn’t seem to be taking the forecast as an opportunity to go on a spending spree — his budget recommendations include about $1.5 billion in unallocated money for 2022-23.

What to expect for K-12

DPI and State Board budget requests

We’ll get into Cooper’s recommendations, but first let’s discuss priorities of two powerful groups: The State Board of Education and Department of Public Instruction (DPI).

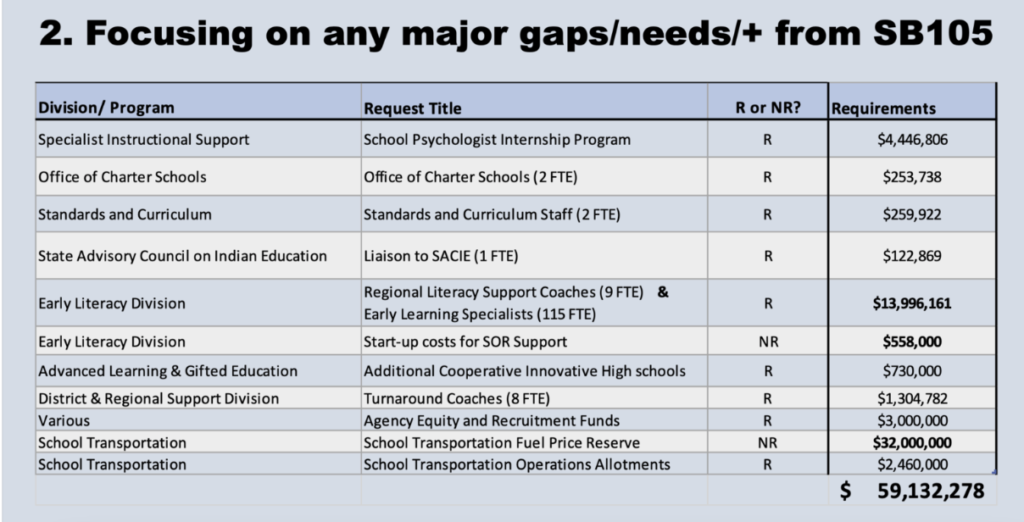

The State Board voted on joint budget priorities between itself and DPI at its most recent meeting. These include nearly $14 million for literacy coaches and 115 early learning specialists, as well as additional funding to cope with rising fuel costs.

Generally speaking, DPI and the State Board are also together in wanting pay increases for teachers, particularly given rising inflation.

But the State Board is separately asking for a couple of items of its own, including advocating for $15 million to fund 115 social workers for school districts and $18 million for 51 positions for DPI’s efforts in turning around low-performing schools.

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt advocated against those options at the recent meeting, arguing that now wasn’t the time to ask for them, particularly given the amount of federal COVID-19 money left over and accessible to districts. She also said the DPI group responsible for turning around low-performing schools isn’t ready to expand its operation.

How did the governor respond?

Cooper’s budget proposal reflects the joint budget ask from DPI and the State Board, giving them the money for the literacy positions and increased funding to deal with fuel costs, among other priorities.

While the governor’s budget doesn’t explicitly grant funding for the 115 social workers the State Board is asking for, it does include $70 million for 850 instructional support positions, which could include social workers, but also school counselors, nurses, and psychologists.

What is the governor hoping to do for students with disabilities?

The governor’s budget also asks for $57 million and $20 million for students with disabilities and English Language Learners, respectively. These items are aimed at removing the cap on funding for these students and providing additional funding. Currently, the state caps funding as a percentage of total students in the district at 13% for students with disabilities and 10.6% for English Learners.

In 2016, the General Assembly’s Program Evaluation Division conducted an evaluation of K-12 funding and found (among 10 other things) that:

- “The allotment for children with disabilities fails to observe student population differences and contains policies — intended to limit overidentification — that direct disproportionately fewer resources to LEAs with more students to serve (the allotment at that time was capped at 12.5%); and

- “The allotment for students with limited English proficiency lacks rationale and fails to observe economies of scale, resulting in illogical and uneven funding.”

Since that report, Cooper has proposed removing the caps twice without success. His current ask is included among other Leandro compliance line items. Don’t worry, we’ll get to Leandro in a bit, but first…

What about teacher pay? And school buildings?

Of course, the biggest ticket item in any budget is salary increases.

The long session budget guaranteed teachers an average 5% pay increase over two years — 2.5% in both years. So, with an additional 2.5% average in the second year, that increase goes up to 5% in 2022-23 under Cooper’s plan.

The governor also wanted more bonuses, including roughly $3,000 more for teachers and some other personnel. Basically, every state employee would get a $1,500 bonus under Cooper’s plan. An additional $500 would go to any state employee making less than $75,000. And then teachers, instructional support staff, and administrators would get another $1,000.

And don’t worry, part-timers — you would get a prorated amount for bonuses you are eligible for based on how much you work.

In addition, Cooper is proposing $500 million for public school construction and $75 million — on top of a previously budgeted $100 million — to fund local teacher supplements.

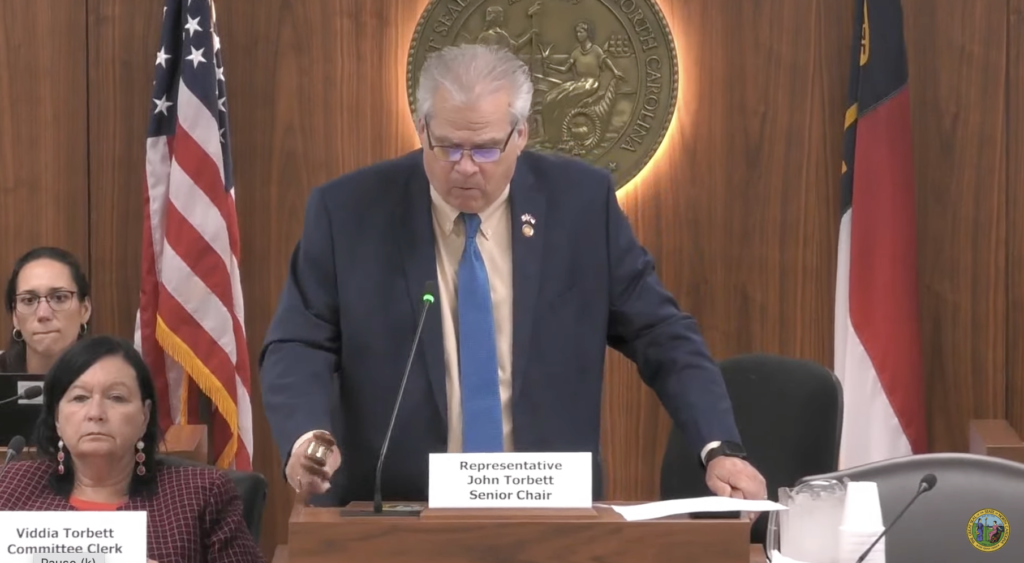

While we don’t know yet what legislators will do on teacher pay or bonuses, we do have a clue about how at least one powerful legislator feels. Rep. John Torbett, R-Gaston, chair of both House education appropriations and education committees, made his feelings on teacher pay clear recently.

“We shouldn’t thump our chest on a 5% pay increase to teachers when you have inflation at eight and a half percent, you have fuel costs over a 100% increase, you have rental charges going up 20%, you have health care going up 14%, and the list goes on,” he said while presiding over a House committee on the future of the state’s education system. “So the 5% pay increase is really a negative by the time everything else comes out.”

You can read more about the governor’s budget here and more about the State Board and DPI budget priorities here.

What about our youngest learners?

Strengthening the state’s network of early childhood care and education was the focus of a recent report from the cross-sector Hunt-Lee Commission, which included state legislators from both sides of the aisle.

The report, released from the Hunt-Lee Commission in April, recommends the General Assembly try some new strategies to address longstanding problems of access, affordability, and low teacher compensation. It suggests funding pilot programs to incentivize more child care for infants and toddlers and to bolster the early childhood profession.

But it will likely not be until next year’s long session that we see legislative action around many of those recommendations, said commission members Rep. Ashton Clemmons, D-Guilford, and Sen. Michael Lee, R-New Hanover, in interviews with EdNC.

While now might not be the time for lawmakers to come up with new programs, we may see legislators debate more funding for the programs we already have. Programs like…

NC Pre-K

Last year’s budget increased the rate child care centers receive for NC Pre-K by 2% for each fiscal year. The program, which serves 4-year-olds from low-income families, has classrooms in both public schools and private child care centers. The bump in the rate is aimed at closing disparities in teacher pay between settings. Centers have long struggled to retain teachers and the pandemic has exacerbated the issue.

This year, Cooper and advocates like the NC Early Education Coalition want to see larger increases in NC Pre-K funding — which is also a component of the Leandro plan. Cooper’s budget includes $41.9 million for the program, including increasing reimbursement rates by 19%. It would also raise how much local agencies can use for administrative purposes from 6% to 10%.

Cooper’s budget also includes $10.25 million in recurring funds to expand early intervention services and an additional $10 million annually for Smart Start, the statewide network of local early childhood organizations. This would add to a recurring $10 million boost from last year’s budget.

Early childhood teacher support

Last year, the House’s budget included funding to expand the WAGE$ program to all 100 counties, which gives education-based pay supplements to early childhood teachers. But the funding did not make it to the final budget.

DPI and the State Board didn’t specify what kind of increases they were looking for. Meanwhile, Cooper’s proposal included an additional 2.5% pay increase for teachers.

Cooper’s budget proposal for the short session gives $26 million in recurring funds for that purpose. A group of 18 early childhood organizations is requesting an annual $36 million, as seen in the document below.

The average starting wage for child care lead teachers is about $10.50 an hour, according to a November 2020 report from the Child Care Services Association.

Many child care teachers are receiving temporary increases in pay through stabilization grants distributed by the state from federal pandemic relief funds — but those funds will run out in 2023.

Cooper’s budget proposal also includes $10 million in nonrecurring funding to explore opportunities to open new early childhood programs at community colleges, which provide professional development for teachers and child care for parents who are earning degrees. He also wants $1.25 million to scale strategies from the Educator Workforce Program, which is aiming to “advance pathways to higher education and employment in early education for 1,000 new early educators in the first two years.”

Subsidy floor

Advocates rallied behind House Bill 574 last year, which would change how the state funds and distributes funding for the child care subsidy program. Subsidies help parents afford child care, but thousands of children are on waitlists across the state.

Subsidies also do not reflect the actual cost of high-quality care and vary greatly from county to county. The state is already studying a better way to model the program, but funding would be needed to reach more families and pay providers more.

The bill would have spent $31.5 million in recurring funds to increase the rates child care centers receive and $94.5 million to establish a subsidy floor (meaning providers would at least receive the state’s average rate).

This session, the same consortium of advocates wants $73 million annually to ensure programs across the state have “adequate and equitable rates that incorporate the true cost of care.” The group says this amount will allow the state to increase the rates to 2018 market rates and establish a statewide minimum rate so lower-income counties are not receiving less to provide the same care.

Cooper’s budget proposal includes $18.5 million in recurring funds “to provide a statewide rate floor in the childcare subsidy program for childcare centers and family childcare homes in lower wealth counties.”

And then there’s Leandro

The Leandro case has been going since the 1990s. In recent years, Judge David Lee started working with plaintiffs and defendants in the case to order a multi-year comprehensive plan that would attempt to bring the state in alignment with its constitutional duty on education.

The case has been to the state Supreme Court twice over the years, with the court finding that the state’s children have a fundamental right to the “opportunity to receive a sound basic education” and that the state had not lived up to that constitutional requirement.

Ultimately, Lee ordered the state to turn over about $1.7 billion from the state’s General Fund to fund years two and three of the comprehensive plan during the biennium.

While the defendants in the case — the ones that supported the comprehensive plan — are called the State of North Carolina, they don’t exactly represent the interests of the Republican-led General Assembly. So, Berger and Moore intervened in the case separately.

You can read the latest here, but a new judge — Michael Robinson — determined most recently that the biennium budget passed last year didn’t fund about $785 million of years two and three of the comprehensive plan.

Cooper didn’t really wade into that battle at all in his budget proposal, except to say that his budget funds year three of the plan.

It isn’t likely that the Republican-led General Assembly would fully fund year three, given lawmakers didn’t choose to do so last year, though it is possible that some of the line items of the plan could get funded. But, as comprehensive plan advocates regularly argue, it is not a menu of options but rather a holistic strategy for achieving a goal.

The community college system

The state has 58 community colleges, and they are considered by many to be one of the chief drivers of the state’s workforce. The system serves nearly 700,000 students enrolled in academic, workforce continuing education, and literacy courses, and in 2019-20, more than 48,000 students graduated with a certificate, credential, or associate degree. So, how did the state’s community colleges fare in the biennium budget last year?

Overall, the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) got more than $1.3 billion in each year of the biennium.

Highlights from that $1 billion investment included a 5% salary increase over two years for community college personnel, minimum wage increases, nearly $80 million in budget stabilization funds, and more than $20 million to recruit and retain faculty.

In addition, the state budget allocated $400 million for capital improvement projects and repairs at the 58 community colleges over four years, and nearly $50 million for equipment and furniture purchases.

According to a press release from the community college system, that budget was the largest the system had received in the last decade. But while leaders were pleased with the budget, some funding priorities remained — including increased funding for faculty and students.

The State Board of Community Colleges approved its 2022-2025 legislative priorities at its meeting in January. That document requests an additional 1% employee salary increase and a 4% increase for student funding in the budget during the 2022-23 short session.

Community colleges receive funding according to their full-time student equivalent (FTE), a measure based on the number of accumulated student hours.

NCCCS students are currently funded at 53% of UNC System first-year and sophomore students in comparable classes, the Board’s three-year request document says, “despite smaller average class sizes and faculty credentials that meet or exceed those in the UNC System.”

“This request, when combined with the salary increase, moves our recurring student FTE value over three years to 66% of equivalent UNC courses that earn the same academic credit for students,” the document says. “This increase will bring North Carolina to the average percentage State funding per FTE student of our four surrounding states.”

What did Cooper want to give community colleges?

Cooper’s budget plan includes an additional 2.5% raise for state employees, which would include community college personnel. That would be on top of the 2.5% raise they were already set to get this year.

His plan also includes those same one-time bonuses for state employees — $1,500 for all, and $500 extra for those making less than $75,000. And again, part-time state employees still get bonuses — just a prorated amount.

Cooper is also proposing about $25.5 million to help “address retention and other labor market needs” at community colleges, and $422,000 at the system office. The budget document states that “agencies may use these funds to address turnover, equity, and compression and to adjust salaries to better compete for and retain talent.”

Other items of note in Cooper’s community college budget proposal

- $50 million to “create additional capacity” at all of the state’s community colleges. The funding is meant to help expand courses, create new programs, and more.

- $10 million in nonrecurring money for grants for an early childhood development center (CDCs) pilot program. The funds will expand already existing CDCs on community college campuses and create additional centers “to increase professional development opportunities for the childcare workforce while also providing additional childcare options to support students completing their degree programs.”

- $15 million of recurring and nonrecurring dollars to increase the number of health care workers trained at community colleges.

- $2 million to expand adult learner pilot programs to additional community colleges, building on the approaches taken in the NC Reconnect Program and other programs focusing on adult learners. EdNC reported on the adult learner initiative in September.

- $2 million recurring to employ eight program assistants in Small Business Centers in each region across the state to coordinate counseling efforts and meet demand for services.

- $10 million nonrecurring funds and one position for the Department of Environmental Quality to establish a grant program for K-12 districts and community colleges to implement energy efficiency, clean energy, and clean transportation projects.

- $500,000 to increase the system office’s capacity to gather and analyze student outcome data.

You can read the governor’s full budget plan here.

Ok, one more thing. We need to address the real question on everybody’s minds…

How long is this going to last?

Last year’s long session was the longest since 1965 at least. Also, it technically didn’t even end last year — the session finally closed in March. But, Moore has said that the plan is for the short session to be, well, short. Maybe lawmakers can follow up their record long session with a record short session?