A remedial plan filed this week by parties in a long-running education lawsuit called Leandro recommends that North Carolina take several actions to strengthen early learning opportunities for young children, including fully funding its NC Pre-K program.

The state’s current allocation covers about 60% of the program’s cost. That makes it challenging to sustain quality and reach eligible children, according to multiple reports and EdNC interviews with local pre-K administrators and educators.

In recent years, counties have declined pre-K expansion funds from the General Assembly because of barriers in the funding structure. Those barriers include a stagnant reimbursement rate as operating costs rise, and a lack of startup funds for new classrooms.

In recent EdNC visits to three pre-K programs in rural eastern North Carolina — in Clinton City Schools, Perquimans County Schools, and a Pitt County child care center — local leaders brought up obstacles to meeting children’s needs that the Leandro plan’s recommendations address: space, transportation, high-quality teacher retainment, and overall funding issues. Greene County Schools administrators talked about a similar struggle: The fixed funding the district receives doesn’t account for teacher experience.

“Every year, we go in the hole for NC Pre-K,” said Melissa Fields, the NC Pre-K program coordinator in Perquimans County, where there are two pre-K classrooms. “Frankly, it’s just not enough to pay our bills.”

A group of business leaders has been pushing for investment in NC Pre-K in recent years and commissioned the 2019 National Institute of Early Education (NIEER) report, which studied the reasons that counties declined expansion dollars. The current funding model requires providers to make up what the state doesn’t cover with a mix of other funding streams and grants.

“That’s very difficult for many counties, and with COVID impacting revenues, has likely become even more difficult,” said Trey Rabon, president of AT&T of NC, in an early childhood legislative caucus meeting Thursday.

Rabon said he is part of a group of 25 CEOs who are advocating for legislators in this session to, “at minimum,” maintain funding for the program, and, if possible, provide more for expansion.

Secondly, Rabon said, the group wants changes in the funding model: adjusting the funding for inflation; reconsidering the 60-40 cost-sharing ratio — especially in the most economically disadvantaged areas; and helping four-and-five-star child care centers become NC Pre-K eligible — “an incremental cost that would quickly expand access across our great state,” he said.

The plan’s 2030 goals

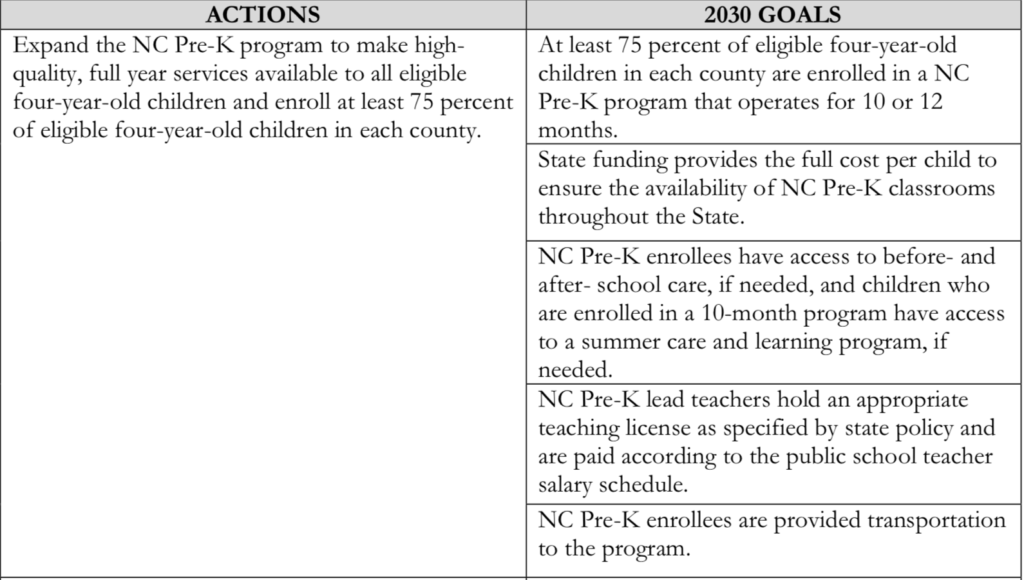

The first early childhood action item in the proposed eight-year Leandro plan is aimed at enhancing NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds. Originally called More at Four and established in 2001, the program has been studied extensively by researchers at The Frank Porter Graham Institute at UNC-Chapel Hill and at Duke University, which have found lasting academic and developmental gains for children.

The Leandro plan, which awaits a ruling by Judge David Lee, calls for full funding for NC Pre-K; extending it to last the whole day and year for families who need it; providing funding for transportation; paying lead teachers on the public school salary schedule; and reaching 75% of eligible children.

The program’s eligibility is based on income and other characteristics, including special needs and limited English proficiency. The NIEER report estimated that in 2017, Pitt and Sampson counties weren’t reaching 25% to 50% of eligible children, and Perquimans wasn’t reaching 52% to 75%.

The General Assembly passed legislation in 2019 requiring the state Department of Health and Human Services to study expansion barriers. Their report, released in February 2020, reiterated challenges with the funding structure.

The program’s dynamics vary across the state. NC Pre-K can exist in both public and private settings and is administered by different agencies in each county, either public school districts or Smart Start partnerships.

Clinton City Schools’ program is administered by the Sampson County Partnership for Children, while the Perquimans and Pitt programs are administered by the local school districts. In Sampson County, there are NC Pre-K classrooms in elementary schools and Head Start agencies. In Perquimans, all NC Pre-K classrooms are in the public elementary school. And in Pitt County, there are NC Pre-K classrooms in public schools and in private child care centers.

‘Stretched very thin — very, very thin’

Administrators in all three counties said they would like to reach more children but have limitations based on space, not knowing exactly how many children they aren’t reaching, and inability to meet families’ needs with current funding.

“We are a self-sustaining program,” said Tanya Turner, Perquimans County Schools superintendent. During a recent visit, Turner told EdNC that the district uses local school budget funds to pay teachers and provide transportation and funds from Title 1 (a federal grant that supports low-wealth schools) to buy other supplies.

The district’s school for pre-K through second grade is full, and smaller K-3 class size requirements mean even less space for pre-K classrooms, Turner and Fields said.

In Clinton, the city schools system has prioritized pre-K on a long list of financial needs, said Kelly Batts, assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction. The district pulls from a combination of funding from an Exceptional Children’s grant, Title 1, and local dollars to reach more children.

“I could see why other districts, if you have an aging roof, or if you have more at-risk kids in high school, whatever it is, that you have to supplement with local dollars, at some point you’ve got to make a decision about, is it worth it?” Batts said. “And in this district, I think we’ve said, it is.”

Batts said the district uses local funds to transport pre-K students on school buses.

“It’s something that we struggle with every year: Are we going to continue to transport pre-K students? Batts said. “So far, our feeling has been, if we don’t, then they won’t come because they can’t get here.”

Both districts said some families use child care in the area before and after school, as well as during pandemic-related remote days.

In Pitt, Catina Moore-Lakhram, the county schools’ NC Pre-K coordinator, said having NC Pre-K classrooms in private child care centers allows the district to reach more children and accommodate parents’ work schedules.

Yet operating NC Pre-K within a private center has its own challenges. Tenisha McGhee, who bought East Carolina Kiddie College with her husband three years ago, said they have to charge some parents of NC Pre-K students for care outside of the NC Pre-K school day to help make ends meet. Child care centers, many of which have barely hung on through pandemic, often operate on razor-thin profit margins. McGhee said she did not pay herself in the first year she owned the center.

“We don’t have a franchise, we don’t have Mom and Pop that can give us money, it’s just us, it’s just me and my husband,” she said. “… With the NC Pre-K funds they do give us, it gets stretched very thin — very, very thin.”

Losing teachers

McGhee said more NC Pre-K funding — as well as more subsidy funding — would allow her to pay her teachers more and cover other expenses. She said she can’t compete with the compensation and benefits a public school district offers and recently lost “an excellent teacher” to an NC Pre-K classroom in the public school district.

“There’s only so much we can offer,” she said.

Even within public school districts, administrators said, keeping experienced teachers in pre-K classrooms does not make financial sense. The state provides $473 per child to public settings, regardless of teacher certifications. In private settings, different rates are provided depending on teacher education levels.

“My previous superintendent moved every pre-K teacher that had greater than five years of experience to kindergarten, because he couldn’t afford it,” said Wesley Johnson, Clinton City Schools superintendent.

“We’re being forced to move veteran, fantastic pre-K teachers because of the way it’s funded, because we don’t get the state allotment for the teacher position, we just get dollars. It puts us in those difficult dilemmas. … It creates us having to fill in these constant voids in pre-K and filling them with beginning teachers.”