The North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) has started offering law enforcement training on “impartial policing,” a first step in the system’s efforts to respond to recent protests of police use of force following the killing of George Floyd in May.

“With the recent conversations about social justice, social inequities, and concerns about policing and policing inequities, because we as a system train the majority of the police officers that are out in the workforce in North Carolina, we felt we had a real opportunity to come to the table and be part of that solution,” said Kim Gold, senior vice president and chief academic officer at NCCCS.

At their June 5 meeting, the State Board of Community Colleges approved up to $100,000 for additional training for police officers in de-escalation, relationship-based policing, and community interaction.

“[Police officers] need the best training and tools available to engage in de-escalation of tense situations and successfully interact with all members of their local communities,” North Carolina Community College System President Peter Hans said during the meeting.

The first of four regional trainings occurred last week at Wake Technical Community College’s Public Safety Education Campus, with the other three to be held in August at Craven Community College, Randolph Community College, and Western Piedmont Community College, according to a press release from the system office.

Responding to the current moment

Over the past two months, state agencies have reacted to the public outcry following the killing of George Floyd by law enforcement.

On June 9, Gov. Roy Cooper created the North Carolina Task Force for Racial Equity in Criminal Justice. Led by Attorney General Josh Stein and North Carolina Supreme Court Associate Justice Anita Earls, the task force will “recommend solutions to stop discriminatory law enforcement and criminal justice practices, and hold public safety officers accountable,” according to a press release. In an email, Laura Brewer, communications director at the North Carolina Department of Justice (NC DOJ), stated they expect law enforcement training to be one of the issues the task force reviews.

The North Carolina Sheriffs’ Education and Training Standards Commission and the Criminal Justice Education and Training Standards Commission also issued a press release detailing how they “provide high quality training and standards for law enforcement officers in North Carolina.” In the press release, they state that the Basic Law Enforcement Training (BLET) curriculum is undergoing regular revision (a process started prior to George Floyd’s killing), and topics being added include procedural justice, ethics, and police legitimacy. The press release also reviews mandatory continuing education for current officers and processes for dealing with police misconduct.

The community college system responded initially by allocating $100,000 for expanded law enforcement training. As EdNC’s Alex Granados reported, some State Board members questioned whether that was enough funding.

“It really doesn’t make sense to me to have just that little bit, when this needs to be expanded really big time,” State Board member Frank Johnson said during the June meeting.

Hans responded that the system had a limited amount of funding available currently. Board member William Holder, a Black man and retired police officer, said while $100,000 might not be enough, it was a “move towards a solution.”

How are police trained in North Carolina?

As Gold pointed out, North Carolina’s community colleges play an important role in training police and law enforcement, both new and active officers. Community colleges offer training for new officers’ BLET courses as well as ongoing continuing education for active police officers.

To become a police officer in North Carolina, you must meet certain minimum requirements determined by the NC DOJ. Those requirements include being a U.S. citizen, being at least 20 years old, holding a high school diploma or passing the GED, completing Basic Law Enforcement Training, and passing the BLET state exam, among others.

BLET programs at community colleges must follow a state-mandated 640 hour course curriculum. This curriculum is developed and revised by the North Carolina Justice Academy based on standards set by two commissions, the North Carolina Sheriffs’ Education and Training Standards Commission and the Criminal Justice Education and Training Standards Commission.

The BLET curriculum is broken into 36 topics, including subject control arrest techniques, ethics, communication skills, crowd management, firearms, motor vehicle laws, and more. The Justice Academy develops lesson plans for each topic, down to the videos shown throughout the course. According to Brewer, these lesson plans can be purchased from the Justice Academy or reviewed in-person at the Standards Division office.

While community colleges must follow the mandated curriculum, they can choose to require additional training beyond the 640 hours. Wake Tech’s BLET program, for example, offers over 100 hours of additional training on “officer survival, public speaking, close-quarter control, and related topics,” according to their website.

Expanded training uses train-the-trainer model for course on ‘impartial policing’

When the community college system began thinking about their role within the context of protests against police use of force, they turned to law enforcement partners to see what would be most helpful.

The system landed on offering continuing education for active officers on “impartial policing” based on curriculum developed by Mitch Javidi, founder of the International Academy of Public Safety, and used by Wake Tech already under the leadership of Jeffrey Robinson, dean of public safety education.

“Impartial policing, or how do you treat all the citizens in your community equitably, is a topic that’s on many people’s minds today,” Gold said when explaining why they picked this topic for additional training.

“What we know through some of the other workshops that we’ve offered and equity work that we’ve done is sometimes people don’t recognize their biases and their responses to people who are different from themselves,” she said. “So [we] really want to make sure that officers have that awareness and they’re able to think through their own biases and respond to people in a way that is impartial and treats members of the community similarly.”

Robinson said that impartial policing is incorporated in the BLET curriculum, but this additional training draws it out and makes it personal for officers.

“I think that [impartial policing and implicit bias] are in some ways embedded in the courses,” Robinson said. “However, I think the difference today is you are now extracting it out of that curriculum and dealing with it even more — it becomes personal now. We’re saying, hey, what are the biases that I as Jeff Robinson bring to the table?”

The system decided that, given that there are many community colleges and limited funds, they would use a “train-the-trainer” model. Through four regional trainings, they hope to train instructors at all 58 community colleges, who will then go back and train officers in their communities at no cost to the officers. In addition to the regional training, the system added an impartial policing continuing education course to their course catalog.

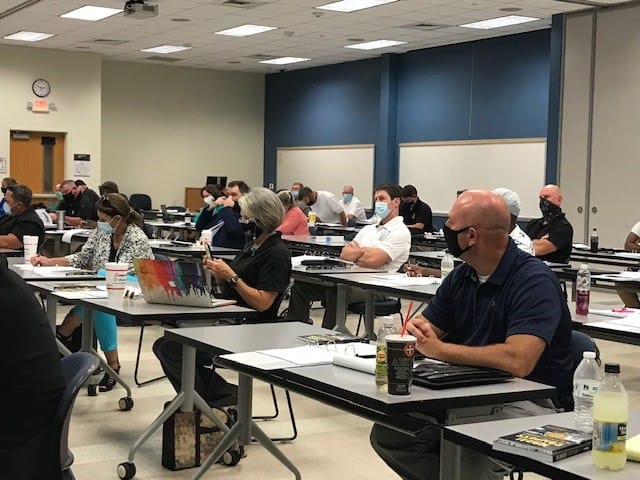

Forty-five law enforcement instructors from 21 community colleges participated in the first training at Wake Tech on July 14 and 15, according to a system office press release. Robinson, who attended the training, said it was one of the best trainings he’s been to on implicit bias and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Javidi, who led the training, walked participants through an exploration of their implicit and explicit biases as well as examining how those show up when someone is under stress.

Robinson said Javidi did a good job of presenting data and information without judgment. “I’ve been in those classes where it turns into a white male bashing, and then people shut down,” he said.

Javidi utilized small breakout groups to encourage participants to get to know one another and talk through their own experiences and personal biases in a small group setting.

“He made sure that the space was safe,” Robinson said. “That’s hard to do sometimes. The people have to be very much receptive to that. We had some very candid conversations and that happened every day.”

What’s next?

The community college system hopes this is the first of multiple trainings and is discussing other actions moving forward. They are looking at offering additional trainings on de-escalation and other topics using a similar model. They are also working with the commissions as they revise the BLET curriculum.

“If done correctly, I think [these trainings] will be life-altering,” Robinson said. “It causes an officer to at least think,” he said, adding that not many officers he knew had been through this type of training that introduced “the challenge of thinking it through or at least being more aware that you have biases.”

“Hopefully as we can start to see success and people can start to see that impact, we can look for other funding to continue to support this effort and make sure that this is the start of a conversation and that the conversations are ongoing because there’s a lot of work to be done,” Gold said.

On a larger scale, Hans recently appointed Thomas Walker, president of Wayne Community College, and Don Tomas, president of Southwestern Community College, as co-leaders of a new System Advisory Council Initiative on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. In a memo announcing the initiative, Hans wrote:

“The initiative will focus on identifying institutional or policy-related inequities limiting opportunities for students, faculty, and staff, and making recommendations to address them. I’d specifically like you to review the State Board Code and sample college policies for elements that may negatively impact students of color. Finally, you will develop guidelines for colleges to use to examine their own policies.”

Last year, the system released their first equity report that looks at access and student outcomes by race and ethnicity. You can read the full report here, and read about Latinx student achievement at North Carolina’s community colleges here.

Scott Ralls, president of Wake Tech and former system president, highlighted the importance of community colleges in providing access to education for underserved students.

“One of the places that we know where we have had significant challenges as a society is in educational differentiation based on geography. It starts when you’re young, based on your zip code, which clearly determines the resources of the school that you’ll go to,” Ralls said. Open door institutions like community colleges are a big part of changing that narrative, he said, but they often receive too few resources.

“It is about law enforcement education, but I think when we start to talk about issues of institutional racism and systemic issues, we have to look at parts of education that have not been given the attention they deserve given the roles they play,” he added.

For Ralls, the past few months have caused him to reflect on how community colleges can better serve their mission, from reaching students to thinking about how they train their own police officers.

“What our society needs is not us changing our mission, but we have to be embracing it and doing more as part of our mission than ever before. So that means both our communities and society paying attention to community colleges … but also then we have to look in the mirror and say what more can we do,” Ralls said.