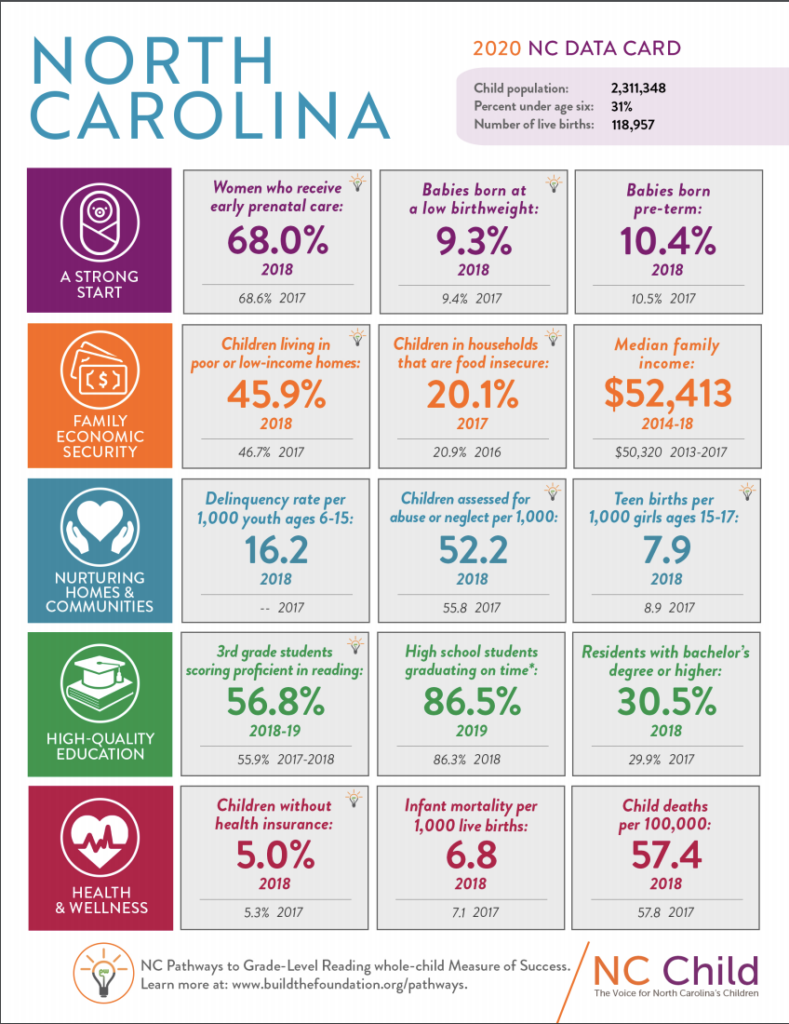

NC Child, a nonprofit organization that focuses on issues that affect young children, has released its 2020 County Data Cards — snapshots of how children and families are faring in each North Carolina county.

Statewide, indicators of health, wealth, hunger, and education held steady overall from previous reported years — yet disparities persisted by geography and race, and nearly every indicator is expected to worsen as families weather the coronavirus pandemic.

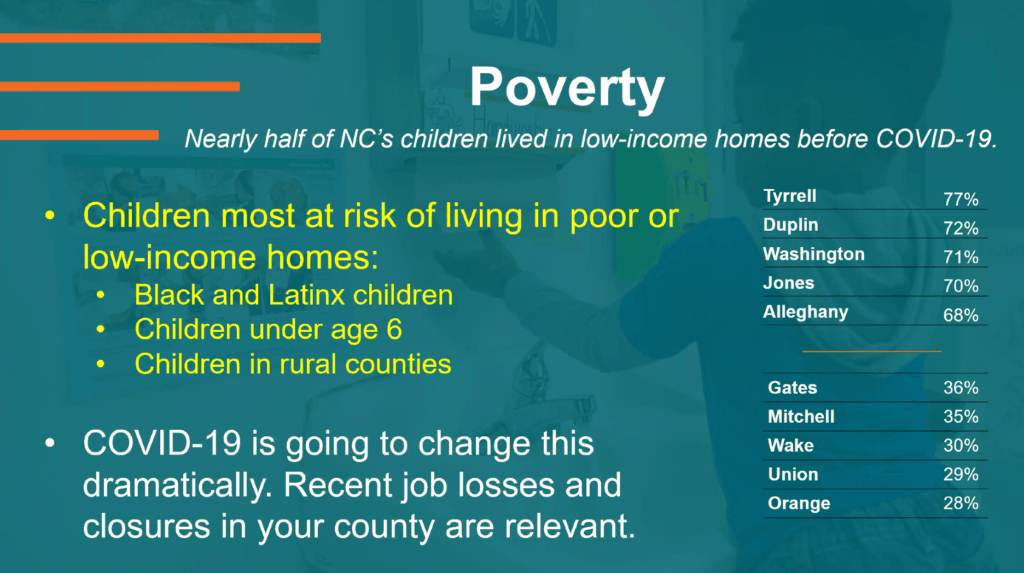

“Before the pandemic struck, nearly half of children in North Carolina lived in a family that was struggling with poverty,” Michelle Hughes, NC Child executive director, said in a news release. “Widespread job losses have meant that many more families are now sliding into dangerous territory. That’s concerning because of the cascade of other traumatic events for kids that can come along with poverty, from losing your home, to a parent struggling with depression.”

Whitney Tucker, lead author of the cards and NC Child’s acting policy director, said the cards’ indicators should be tracked going forward and should ground decisions on funding and policy. She said she hopes the cards will be used on local levels to push policies that address groups of people whom the cards show to be disparately worse off: people of color and people in rural areas.

“Think about whether state and local decision-makers are doing what’s needed to protect the families of young children,” Tucker said. “If we’re talking about poverty, are there approaches that could be better targeted to black and Latinx communities? Will rural counties receive what they need to recover at the same rate as urban counties? Rather than talking generally about whether or not there are approaches that are meant to decrease poverty overall, because a lot of the time, we just don’t see that trickle down to the groups that are most negatively impacted.”

Tucker encouraged users to disaggregate the data by county and by race.

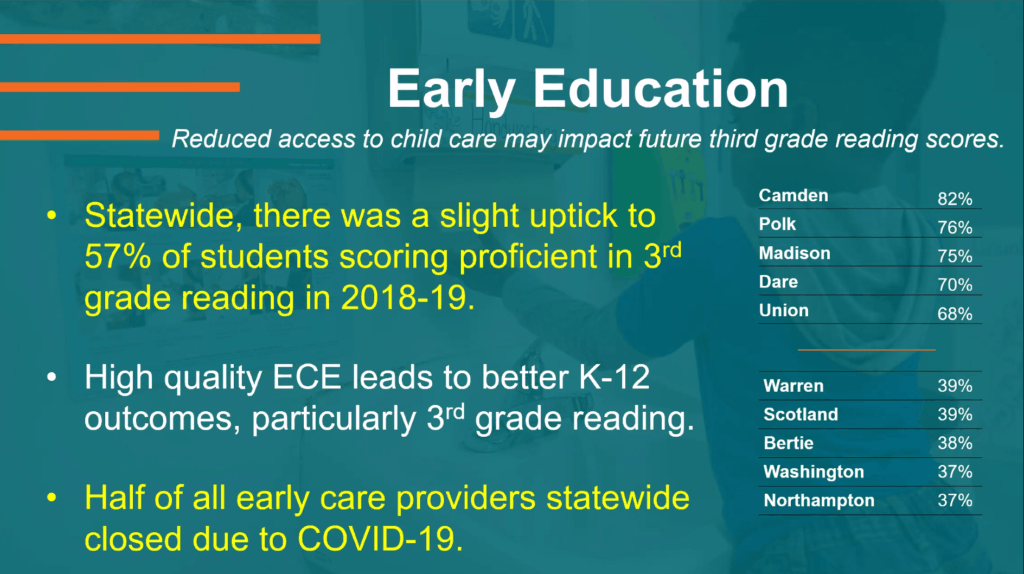

Take third-grade reading scores, which the cards use as an indicator for access to early education. Tucker, speaking on a webinar Wednesday, highlighted a small uptick in the overall proficiency rate from the previous year. In 2018-19, 57% of third-graders scored as proficient readers on end-of-grade tests — up one percentage point from the previous school year.

But a look into the counties with the highest and lowest proficiency rates (shown on the slide below) showed very different realities: from 82% in Camden County to 37% in Northampton County.

“There are areas of the state where kids are getting a vastly different level of education and access that is affecting these third-grade reading scores,” Tucker said. “We know that every child, when given the right conditions and opportunity, can thrive. … We need to look into that more to figure out what’s working and if it’s replicable.”

With half of child care centers closed due to COVID-19, Tucker said relief is needed to ensure equitable access to early education.

“We know that the reduced access to child care that’s going on currently is really likely to impact future third-grade reading scores,” she said.

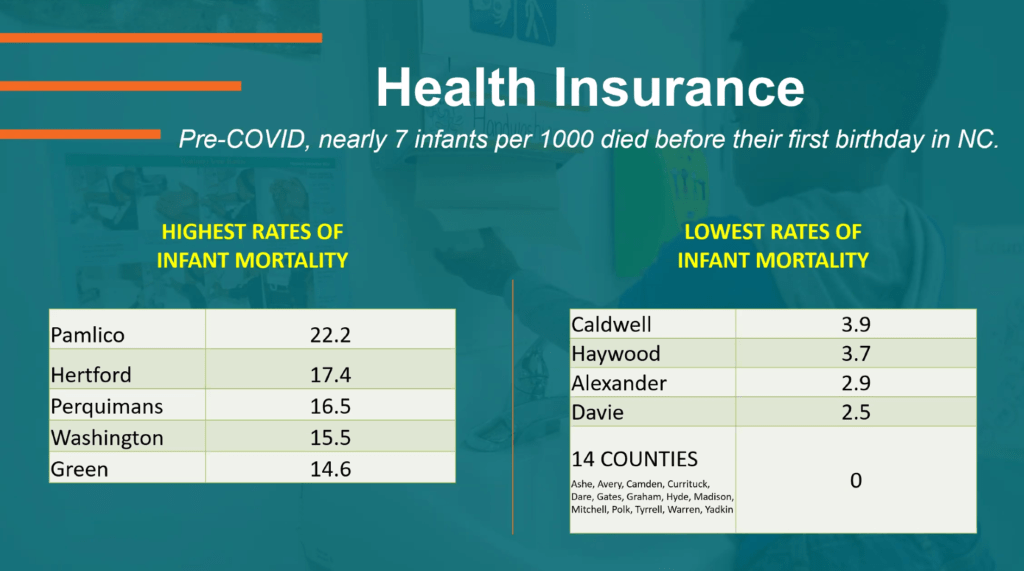

Tucker lifted up infant mortality rates as another example of inequitable outcomes. The state’s overall ratio of deaths per 1,000 births fell to an all-time low in 2018 at 6.8. Yet the disparity between white and black infant deaths remains: the white rate is 5.5, while the black rate is 12.2.

“There is something different that is happening in the way that we are treating black mothers and black infants that is leading to higher death rates across the state,” Tucker said.

Reducing this racial disparity is a statewide goal in the NC Early Childhood Action Plan and has been discussed by state policy leaders over the past year.

Tucker also broke down this data by county, listing the highest and lowest rates (shown on the slide below), which range from 22.2 in Pamlico County to 2.5 in Davie County to 0 in 14 counties. Some of this variation has to do with counties’ population sizes, Tucker said. Most of the time, she said, racial disparities were driving high rates at the local level.

“A lot of times the overall infant death rate was pretty high mostly because there was a really significant racial disparity,” she said.

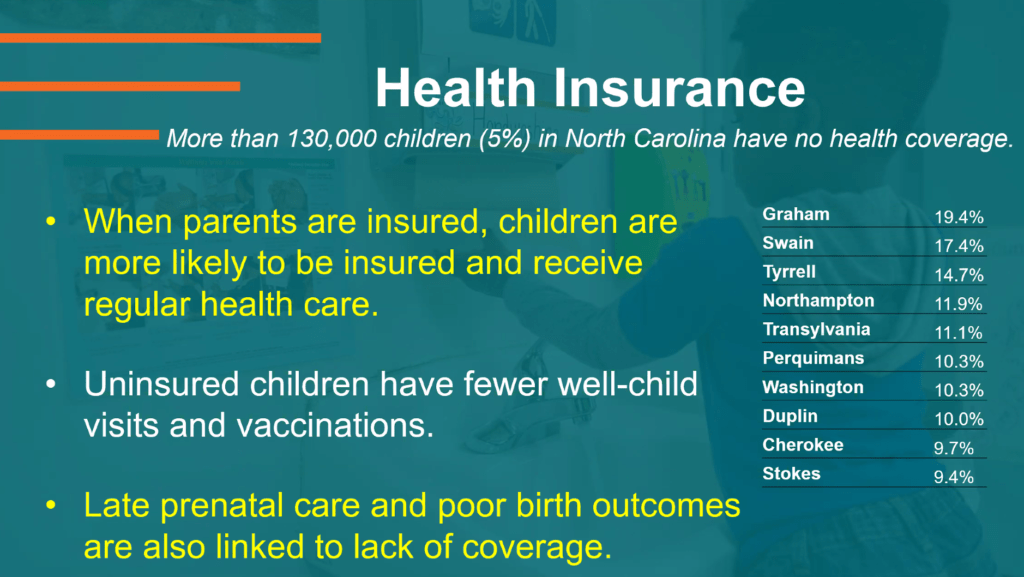

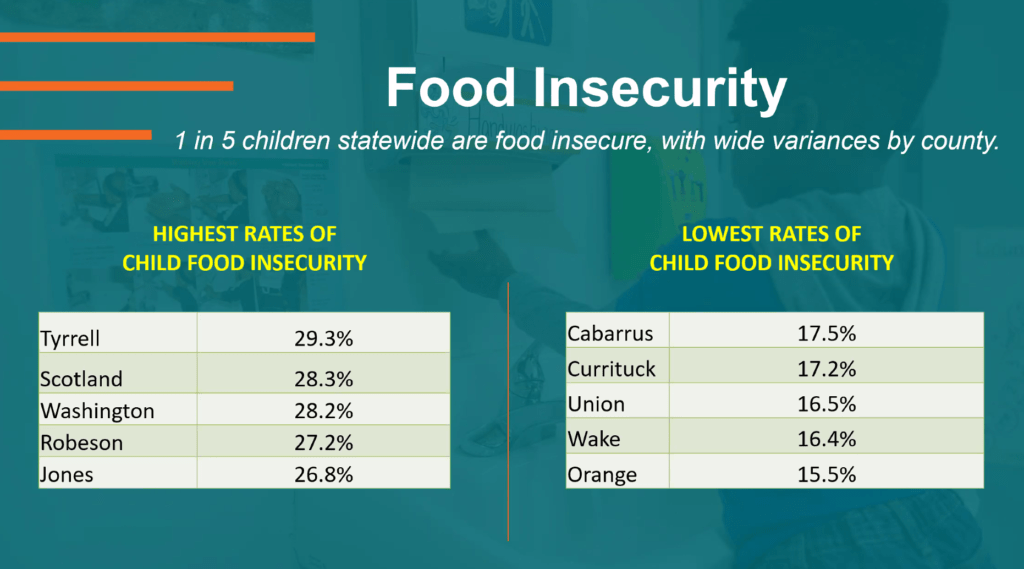

Issues like poverty, hunger, and health coverage showed similar patterns: wide variation depending on where children grow up and their race. And in each of these areas, Tucker said, the pandemic adds a distressing layer.

Pre-pandemic, nearly half of children were living in poverty, and both black and Latinx children were more likely to be living in poor or low-income households. Find the highest and lowest poverty rates in the slide below — which range from 77% in Tyrrell County to 28% in Orange County.

Five percent of children across the state did not have health coverage in 2018, which Tucker said is linked to the disparate birth outcomes, such as infant mortality. That figure was as high as 19% in Graham County and 17% in Swain County.

Twenty percent of children were food-insecure in 2017, with the highest rates of hunger in eastern North Carolina counties.

Tucker also presented policy solutions to address some of these needs, including the expansion of Medicaid, food assistance programs like SNAP, WIC, and TANF, and investments in early education.

Tucker said investment is needed throughout families’ and child care centers’ recovery from the fallout of the pandemic.

“We want to make sure that even after the emergency period has ended, and families aren’t at this immediate risk of COVID exposure, that while there is still this economic uncertainty and a lot of people are still unemployed and unable to afford food, that they’re able to keep access to these programs to get them food and also cash assistance that they need to keep a lifeline…. to keep kids in stable environments,” she said.