Child care centers remain in the challenging position of supporting North Carolina’s working parents with insufficient resources, center leaders and advocates say.

In the first phase of the state’s plan to reopen after the coronavirus shutdown, centers may now care for children of working parents rather than just children of essential workers. A new application to reopen, issued by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), requires centers to meet health and safety guidelines to protect children and staff from potential COVID-19 outbreaks.

Yet many centers are still reeling from the shutdown, which brought significant revenue loss, closures for almost half of centers, and risky work for the ones that stayed open to care for children of front-line workers. A third of North Carolina centers responding to a survey by the National Association for the Education of Young Children said they would not survive closing for more than two weeks unless they had public investment.

As some centers do reopen, they may not have the staff or resources to meet the necessary guidelines, said Michele Rivest, the NC Early Education Coalition’s policy director.

“Telling programs they have to meet these standards isn’t enough because some don’t have the capacity to meet these standards,” Rivest said.

DHHS has, in many ways, been a national leader in early announcements for industry supports, said Dan Wuori, director of early learning at The Hunt Institute. For April and May, the department is providing bonus payments for child care workers and staff, continued subsidy and NC Pre-K payments for open and closed centers, and a new emergency subsidy program to pay for care for essential workers’ children. An announcement last week said DHHS will also give operational grants to centers that have remained open.

Advocates are pushing for those supports to continue throughout future phases of reopening and recovery.

“It can’t just be a cliff at the end of the month or you’ll just see programs close that have tried to reopen,” Rivest said.

Kristen Idacavage, director of Kids R Kids Learning Academy in Charlotte, said she is more concerned about long-term help than short-term needs. Her center, which serves infants to 12-year-olds, has remained open and, over the last two weeks, has gone from serving about 75 children to about 100 — still less than half of its normal enrollment.

“What we need to think about is being able to sustain centers that are open and that open back up who may not feel ramifications financially until the fall, until early next year,” Idacavage said. “Is DHHS thinking about what centers are going to need not now but six months from now? … What if there’s a second wave of this that everybody says is coming?”

Marsha Basloe, president of Child Care Services Association, says she is hearing from centers in a variety of situations — some reopening as soon as possible, others waiting until there’s more need in their community. CCSA and the NC Partnership for Children have set up a COVID-19 Relief Fund, which will give out small grants to about 1,000 centers for cleaning and safety supplies.

She said the state’s efforts have acknowledged child care’s importance, but she echoed the need for more.

“It’s necessary but insufficient,” Basloe said of the current relief going to centers. She said she hopes the crisis will bring longer-term change for the early childhood workforce in the forms of higher compensation, health care coverage, and paid sick leave.

“If we could pay them more during COVID, aren’t they still worth it?” she said.

State relief package

The state’s first relief package determining how the state will spend federal funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act did not allocate the level of child care relief that advocates hoped. Advocacy organizations asked the General Assembly for $185 million for increased pay for workers, sanitation and health supplies, and to make up lost revenue for both open and closed centers.

“Overall, we as a state have not recognized how essential child care is and therefore have not yet dedicated the funding that that infrastructure is going to need to stay open and be ready when the economy opens again,” said Michelle Hughes, NC Child executive director.

Top concerns — especially for smaller centers in low-wealth counties — are centers’ struggles to pay operational and staff costs, their low capacity to navigate loans and financial solutions, and continued low enrollment as parents who have lost their jobs do not bring their children back.

“It’s not going to be easy for folks to reopen, I don’t think,” Hughes said.

Passed two weekends ago, the state relief bill put child care response into a broader $19 million line item that included funds for food banks, child protective services response, and homeless shelters. The bill is unclear how much of the $19 million would be used for child care centers.

Child care workers were also included in categories for protective gear and for antibody testing.

The bill also included $48 million to the Child Care Development Fund, which is money DHHS is already using for the emergency child care response, according to the NC Early Childhood Foundation.

The state still has about $1.9 billion in CARES Act funding to allocate, and will return to session May 18.

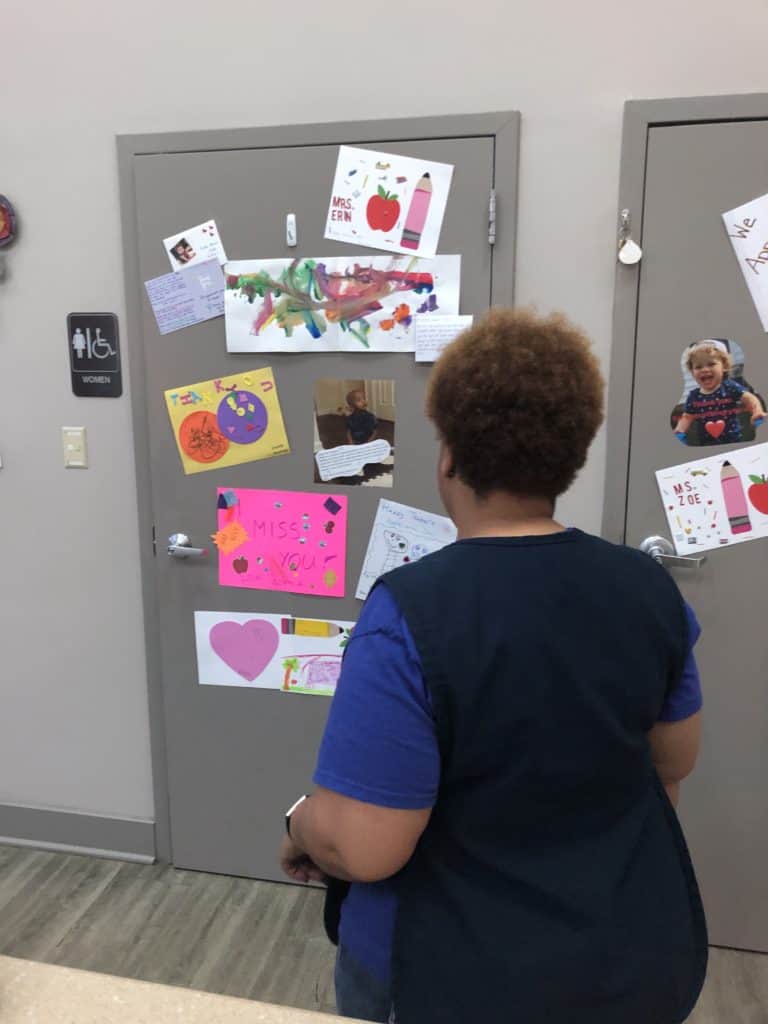

Teachers at Kids R Kids Learning Academy in Charlotte are surprised with posters from students and parents during Teacher Appreciation Week.

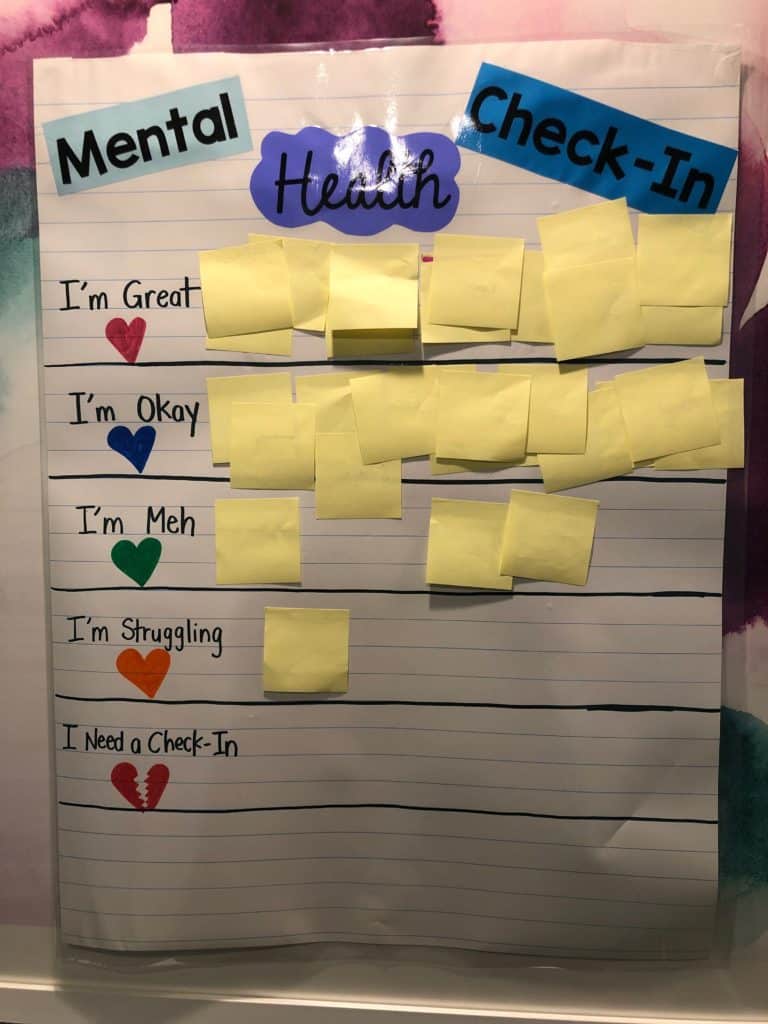

“We’re trying to provide more direct opportunities for them to share,” said Idacavage about her staff’s well-being throughout COVID-19.

Federal money directly to DHHS

Separate from the state’s relief allocations, the federal government sent $118 million in Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG) funds from the CARES Act directly to DHHS. DHHS Communications Manager Kelly Haight Connor said the department is using this money for the emergency child care subsidy program, bonus payments for child care workers, subsidy payments, and parent copayments in April and May.

“NCDHHS is actively exploring additional ways to financially support child care providers with the remaining CARES Act funding,” Haight Connor said in an email last week.

Across the country, this funding stream is being used to support child care programs in different ways, which The Hunt Institute has been tracking. Wuori said most states that have released spending plans for CCDBG funds are providing sustainability grants to centers to ease their revenue loss.

“The purpose really is to make sure centers are still able to pay rent, pay payroll, with the hope that when we come back out of this, this crisis hasn’t put child care providers out of business.”

States, similarly to North Carolina, are also using the funds to cover essential workers’ child care, with varying income caps on those programs. Wuori said only one other state, New Mexico, has provided child care workers with bonus pay. The state’s recognition of the workforce has been greatly needed, he said.

“They’re being asked and being treated in a lot of ways like first responders and being acknowledged as first responders, but in the grand scheme, they’re treated very differently from a lot of other first responders,” Wuori said.

“They don’t have the same kinds of compensation and benefits that we would typically associate with those first responders. So that North Carolina recognized that and really took on a national leadership role in its acknowledgment of that workforce, and … frankly the potential danger of the work they were doing during that time, really makes the state stand out as special in that regard.”

DHHS is hosting webinars for more information on reopening centers, meeting safety guidelines, and operational grants today and Friday.