|

|

In this special report, EdNC looks at how the pandemic impacted education and what that means for the future. Read the rest of the series here.

When the pandemic forced community colleges and four-year colleges and universities to close their campuses and shift to remote instruction in spring 2020, many thought four-year colleges would see huge enrollment declines while community colleges would see an influx of students.

Instead, community colleges both across the country and in North Carolina saw fewer students show up this year as students dealt with job losses, child and family care responsibilities, broadband challenges, and more.

Below, we explore the impact of the pandemic on different parts of postsecondary education in North Carolina, including community college enrollment, the state’s myFutureNC attainment goal, information technology (IT) infrastructure, FAFSA completion, early colleges, and short-term workforce training.

Share your thoughts with us by tweeting with the hashtag #PandemicSchoolYearNC.

Community college enrollment declines

By Emily Thomas and Robert Kinlaw

Enrollment at community colleges in North Carolina fell 11% in fall 2020 compared to fall 2019, a stark contrast to the 4.4% increase they saw one year prior.

The declines were largest among workforce training and basic skills courses: Workforce training dropped 22% from the previous fall and basic skills dropped 51%. Curriculum programs saw a 6% decline from fall 2019.

Community college leaders said the declines were mostly the result of the pandemic. Students struggled to complete online classes, stay enrolled, and balance the added responsibilities pandemic life threw at them.

“Students are balancing teaching at home, having to change hours because of either being laid off or their job responsibilities changed. There are just so many variables in their life that changed, and they couldn’t manage school anymore,” said Jason Hurst, president of Cleveland Community College.

There was also fear of the virus, and access to broadband was a challenge for some students, said John Gossett, president of Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College.

“[Students] don’t have access to high speed internet — either they can’t afford it, they can’t get it because of their location, or they don’t have a device at home to access their classes,” Gossett said.

The sharp drop in enrollment could spell trouble for the state’s attainment goal, which is to ensure 2 million North Carolinians have a high-quality credential or postsecondary degree by 2030.

“We know that delays in enrollment or the need for individuals to halt their higher education pursuits can decrease the odds that a student will earn a degree or credential,” said Cecilia Holden, CEO and president of myFutureNC.

Not all colleges experienced enrollment declines, however. Of the 58 community colleges, four avoided enrollment declines during the pandemic.

In interviews with leaders from three of these colleges, they credited several strategies as key to their success: returning to in-person learning as quickly as possible, aggressive marketing to students who dropped out or were on the verge of dropping out, and moving student services online in the wake of campus closures.

For example, several colleges used hybrid classes to offer the option of returning in person or remaining online depending on each student’s individual comfort level. That was especially important for technical programs that rely on hands-on learning, colleges said.

Community colleges are known for offering extensive wraparound services — from food pantries to clothing closets — and robust financial aid that, in some cases, offers free tuition to residents in their service areas. During the pandemic, advising appointments and other support systems had to be brought online in a way that replicated the in-person experience as closely as possible.

Similarly, it was critical to meet students wherever they were with informational updates on the pandemic. That meant sending emails, postcards, social media posts, website updates, and more. The hope was that if a student missed information on one platform, they would see it on another.

As colleges look to the coming year, many are hoping to regain enrollment they lost by returning to fully in-person learning while still providing online learning options for those who choose.

Progress towards the state’s attainment goal

By Emily Thomas

For years, North Carolina was one of a handful of states that did not have a statewide goal for educational attainment. That changed in February 2019, when the myFutureNC Commission announced a postsecondary attainment goal for North Carolina: 2 million North Carolinians ages 25 to 44 with a high-quality credential or postsecondary degree by 2030.

Over the following year, the commission became a nonprofit organization with the goal of closing the educational attainment gap in North Carolina. In November 2019, Cecilia Holden was tapped as the first president and CEO of myFutureNC.

One year after the announcement of the goal, hundreds of business, workforce, and education stakeholders convened to discuss how to increase postsecondary attainment at the local level. One month after that, COVID-19 hit and threw everyone’s plans out the window.

“We had our big kickoff in February — and then immediately came to what some people will characterize as a screeching halt,” said Cris Charbonneau, director of advocacy and engagement at myFutureNC.

Despite the pandemic slowdown, myFutureNC has launched several statewide efforts over the past year, and Charbonneau said there have been some silver linings.

“COVID has allowed us to accelerate in ways that people found relevant and meaningful,” she said. “It’s really given us an opportunity to meet in ways that might have taken months to really convene folks together.”

Last summer, myFutureNC published a state-level attainment dashboard that outlines the state’s progress toward the attainment goal, using such key indicators as FAFSA completion, ACT performance, and labor market alignment. They also published county-by-county data profiles using the same key indicators.

The hope is that the data can be used across sectors to better coordinate efforts in pursuit of the goal.

myFutureNC also worked with a group of nonprofits to launch NC First in FAFSA, an initiative to get more students to fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). In 2020, North Carolina students left an estimated $107 million on the table by not filling out the application, and FAFSA completion rates have been down this past year compared to previous years due to the pandemic.

“Because of this pandemic, the students in Class of 2020 and 2021 are facing challenges no other students have had to deal with before. But we want to make sure they still have the opportunity to continue their education and accomplish their dreams,” said state Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt in a press release announcing the initiative. “Completing the FAFSA is a pivotal first step in helping them do that.”

Moving forward, myFutureNC sees educational attainment as a critical part of the state’s pandemic recovery.

“When we think about COVID and those that have had job loss or their focus might have changed, we need to reskill and upskill. Learning does not just stop because you’ve earned your high school diploma,” said Charbonneau.

The pandemic also shed light on communities that are disproportionately affected and highlighted the importance of additional support for students coming from low-income backgrounds, communities of color, and those who are the first generation to go to college, Charbonneau said.

“Educational attainment is the short-term recovery strategy and the long-term resiliency plan for our state’s economy,” said Cecilia Holden, president and CEO of myFutureNC. “A better educated North Carolina is the gateway to economic prosperity and upward mobility for all citizens.”

Outdated IT and cybersecurity systems

By Emily Thomas

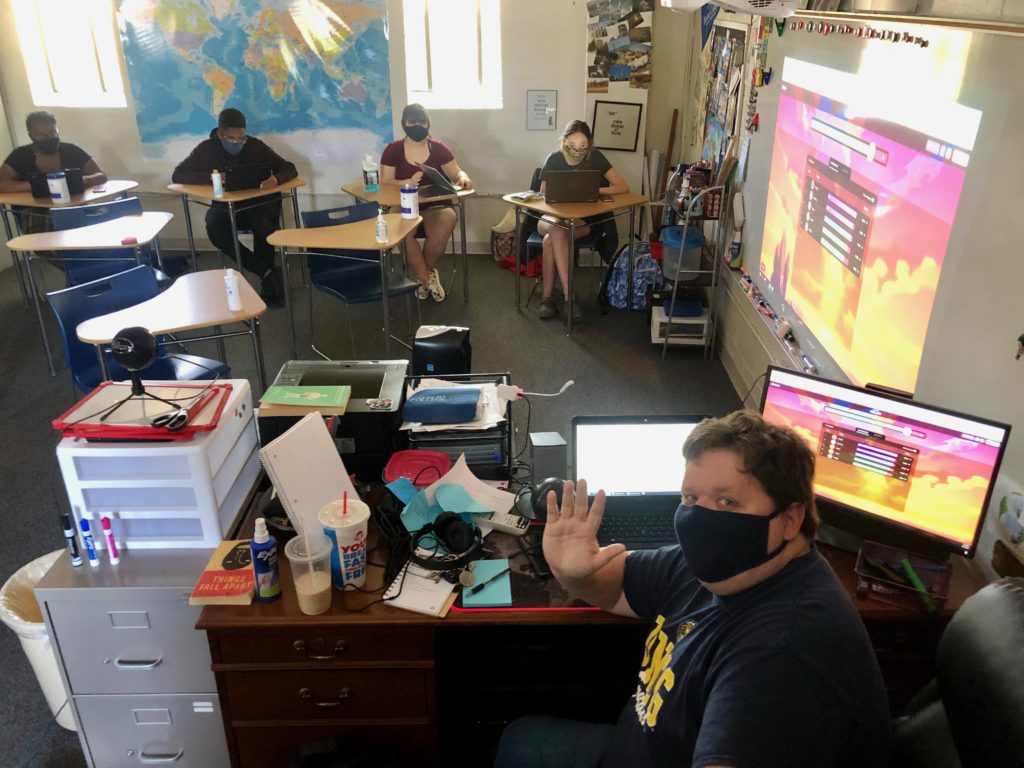

In March 2020, community colleges across the state had to shift almost every class online.

“It was a furious pace for an entire week,” said Christina Toy, coordinator and instructor of oral and written communications at Caldwell Community College and Technical Institute (CCC&TI). “Training like I’ve never seen in my life. We were literally taking all of our classes in every format and transitioning them to an online format.”

Even though every instructor at CCC&TI had a Moodle site (Learning Management System), not every instructor had experience teaching online.

“We have some very talented, innovative online instructors,” Toy said. “But we also had a group of faculty who had never taught online before.”

Colleges had at most two weeks to make the shift online, and then most employees left campus.

“When we packed up on our last day to go home, I remember standing in the doorway of my office looking at it and thinking, ‘I wonder how long we’ll be gone,’” Toy said.

North Carolina community colleges spent the next year trying to mitigate challenges surrounding online learning, IT infrastructure, broadband access, remote working, and a host of other issues brought on by the pandemic.

Prior to COVID-19, Piedmont Community College (PCC) analyzed their data to ensure that students who were taking classes online had an equivalent experience to those who were taking classes face-to-face. They found the gap was small.

“What we forgot is there’s a difference of who raises their hand and says I want to have a completely online experience versus those who choose face-to-face,” said Pamela Senegal, president of PCC. “COVID shifted that paradigm and put people in a situation to have instruction in a manner that they don’t believe is best for them.”

But it wasn’t just preference of class format that caused problems. Many students did not have an adequate device for online classes or had trouble connecting to the internet.

Senegal pointed out that 43 of the 58 community colleges in North Carolina are considered rural.

“We already knew McDonald’s was the place students were going to do their homework pre-COVID,” Senegal said. “They were sitting inside McDonald’s using their Wi-Fi.”

When the dining rooms closed, PCC asked businesses to make their signal available so that people could sit in their cars and do their homework.

And while many colleges extended their Wi-Fi and handed out devices and hot spots, it wasn’t a fix for everyone.

“I would take work any way I could get it,” said Toy. “I accepted photos of handwritten work. I accepted work through email. I even accepted speeches through FaceTime.”

Faculty and staff struggled with internet connectivity, too.

“Like many colleges, we had to deal with faculty who may not have adequate internet access,” said Susan Wooten, vice president of technology and instructional support services at CCC&TI.

Even for Senegal, internet connection is a problem.

“When both my son and I are on, my internet connection becomes unstable,” Senegal said. “If Ireland in one generation can get their entire island wired, then why can’t we?”

IT challenges aren’t limited to devices and broadband. Colleges had to be innovative and revamp entire IT systems — systems that are decades old.

“When you look at the Community College Information Technology system, it’s basically a 20-, 25-year-old system,” Surry Community College President David Shockley told lawmakers back in March 2019.

CCC&TI had to think about remote access for workers and make sure it was secure.

“It’s not something we’ve ever done on this level with this many employees,” Wooten said.

Many colleges used federal relief funding to purchase new software and programs. But those funds won’t be available long-term. And decisions will need to be made to determine what they keep and what they pull back on.

“Now we have to go back and think, ‘how do we sustain all of this?’” Wooten said.

The pandemic, along with recent cyberattacks, continues to reveal the need for IT personnel.

Community colleges hire IT personnel with little experience, said Senegal. They’ll invest in them, helping them gain credentials along the way so that they can manage systems locally. Inevitably, those same personnel realize they can go somewhere else with those credentials and make twice as much money, said Senegal.

“This is an issue across the state,” Senegal said, “the lack of a deep bench of IT expertise within our colleges.”

Wooten agreed.

“If I need a data miner or a programmer, I can’t afford them,” said Wooten. “We grow them ourselves here, but we can’t afford them.”

To deal with these challenges, the community college system has been asking the state for funding to upgrade their IT systems. This legislative session, the system is seeking $3.5 million in recurring and $28.5 million non-recurring to upgrade the IT system serving its colleges.

“We need to think of ourselves as the third largest system in the country,” said Central Piedmont Community College president Kandi Deitemeyer. “And if you want to be the best at delivery, if you want to be the best service model for your students and for workforce development, we have to have beyond what I would consider a modernized system.”

Fewer students seeking financial aid

By Analisa Sorrells

The Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) is a form that’s used to determine students’ eligibility for federal financial aid in pursuing postsecondary education — and at times also determines state, institutional, and private aid.

Since the pandemic began in March 2020, almost 1.5 million North Carolinians have applied for unemployment benefits. That means even more families could need aid now, making the FAFSA even more important.

“FAFSA is the first part of financial accessibility,” said Scott Ralls, president of Wake Technical Community College. “We hope and we strive that nobody will decide not to go to Wake Tech because of finances. But the first step is always filling out the FAFSA.”

According to a 2020 report by Education Strategy Group (ESG), students who complete the FAFSA are more likely to enroll in higher education – 90% of those who complete the FAFSA attend college directly after high school, compared with 55% of students who don’t complete it. And those who complete the FAFSA are more likely to persist in their coursework and obtain a degree. However, fewer than two-thirds of graduates nationally complete the FAFSA each year, leaving an estimated $3.4 billion in aid on the table annually.

Numerous barriers exist to completing the FAFSA — including form complexity, a lack of awareness, and parental mistrust of providing personal information. And with many North Carolina high schools operating under remote or hybrid instruction due to COVID-19, this school year’s FAFSA cycle has looked different than previous ones.

“Too often, we know that students and their parents sometimes aren’t aware and they don’t know the importance of it,” Ralls said of the FAFSA. “They think that college is too difficult to reach or may not be for them because they think they can’t afford it, not knowing all the resources that are there.”

Before the pandemic, many schools relied on in-person events to encourage FAFSA completion and assist students and families with filling out the form. Throughout the pandemic, counselors and college advisors have found new ways to offer support, from virtual advising sessions to drive-in events with masks and social distancing.

On a Saturday morning in April, Wake Tech held FAFSA advising events on two campuses as part of a statewide partnership between myFutureNC, the College Foundation of North Carolina, and GEAR UP. After checking in, students were paired with a financial aid specialist from the college who walked them step-by-step through filling out the FAFSA.

“So many students have just been disconnected from help and support in the pandemic,” said Brian Gann, vice president of enrollment and student services for Wake Tech. “With it (FAFSA) already being hard, then add in all the challenges everybody has faced during the last year, it just becomes that much more important that we keep the door open as best we can for people to get through this process.”

As of April 30, nationwide FAFSA completion rates were down 5.8% from the previous year. North Carolina’s FAFSA completion rate was 48.2% as of April 30, with 51,094 students having completed the form. That’s according to the FAFSA tracker by Carolina Demography and NC First in FAFSA, a collaborative effort by myFutureNC that focuses on increasing the number of high school seniors who complete the FAFSA. The tracker includes detailed FAFSA completion data for individual high schools and districts.

Looking at what the future may hold for boosting FAFSA completion rates, Cris Charbonneau, director of advocacy and engagement for myFutureNC, highlighted two key areas: strengthening an emphasis on early career planning and expanding access to additional advisors and mentors. Charbonneau said that additional advising resources can build off of the guidance that school counselors provide by giving families another credible source of support outside of the school building.

“Being able to say ‘Hey, here’s an additional mentor or guidance group or counselor that also understands the cultural perspective that you’re coming from and perhaps maybe some of those language barriers’ — it redirects them and also helps to better navigate a system that maybe some of those families just are unfamiliar with,” Charbonneau said.

Early college as a model to accelerate learning

By Liz Bell

Strong relationships — between students and staff and between peers — have always been at the heart of Edgecombe Early College High School, principal Matt Bristow-Smith said. Yet he said he never could have imagined the role those relationships would play throughout a school year of pandemic learning.

They “gave us a really strong running start into the pandemic,” Bristow-Smith said.

“All early colleges, I think — either implicitly or explicitly — have an equity commitment, that every child in their school is seen, is known, is affirmed, is lifted up, is treated as an individual,” he said.

Across the state, about 100 early colleges make differences in children’s success in high school and beyond, differences that research has found to be statistically significant. The students take both high school and college courses and often earn credentials or degrees by the end of high school.

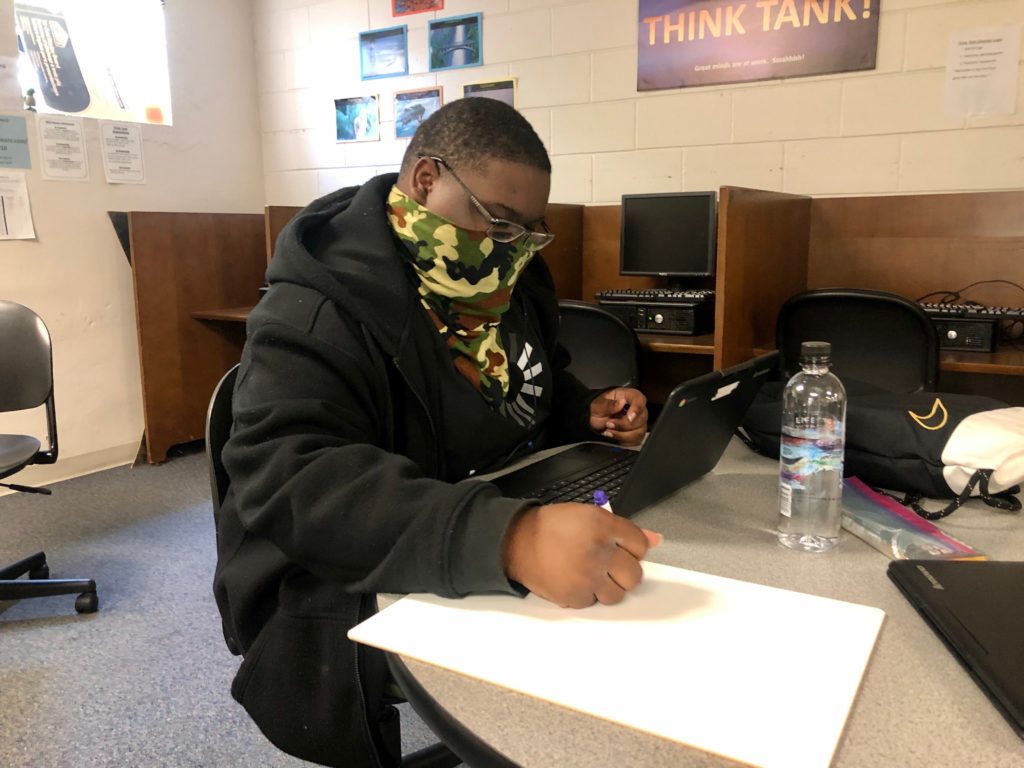

This year, early college students added a pandemic into their already difficult balancing acts. That showed up in different ways throughout the year as courses went completely remote and then phased back into some in-person instruction.

At Rutherford Early College High School in Spindale, college liaison Andrew Bradshaw saw many students drop off in engagement during remote learning. He started offering one-on-one support. One of his standard questions, he said, is “How many hours are you working?”

The answers surprised him and also made sense of students’ drops in academic performance.

“We found out that students were working a lot more hours than they can reasonably juggle with high school courses, college courses, trying to have some kind of social life, plus working 30 hours in a grocery store or wherever,” Bradshaw said. “When you’re trying to manage all that, sometimes it’s easy for academics to become kind of lower on your priority list.”

Bradshaw and high school staff were able to have conversations with students, sometimes bringing in parents as well. The high school started offering a program called “I See You,” which scheduled in-person weekly or biweekly meetings where students could get help on coursework from high school teachers. Even a small in-person connection went a long way, Bradshaw said.

“It improved nearly every student who took advantage of that — I mean huge improvements in college and high school, and not just academically,” Bradshaw said.

Bristow-Smith said he heard similar stories from his students, some of whom were taking on breadwinning responsibilities in their families due to job loss or financial hardship from the pandemic.

“What it came down to is, if we didn’t do something different, we would lose these kids,” he said.

Erin Swanson, director of innovation for Edgecombe County Schools, pushed school leaders to create “hub and spoke” models to solve varying challenges their students were facing. The school was the hub, Bristow-Smith explained, and the spokes were reaching out into communities.

For six seniors, that meant reimagining their senior projects. Bristow-Smith helped one student who was working full-time at Pizza Inn design her project around her work experience. The school put the student’s manager on contract to be her mentor and to place the student on a track to become a manager by the end of the semester.

“What was essential is that we sat down and we talked with them,” he said. “That’s what human-centered design is really all about — bringing scholars into their learning design process.”

For another student who was taking care of her young nephew, Bristow-Smith connected her with an early elementary teacher and built early childhood education credentials into her project.

“In some ways I feel like this pandemic has been a stress test of the early college model, and our ability to not only withstand the trials that we’ve dealt with, but to thrive,” Bristow-Smith said, “to thrive in an environment that demands innovation. It demands equity to meet the moment, and our schools are uniquely positioned to do that.”

As students and families recover from the pandemic, the early college model could offer lessons for increasing postsecondary access and attainment.

“The early college model really can force us to think differently about how we organize educational systems,” said Julie Edmunds, program director for secondary school reform at UNC-Greensboro’s SERVE Center. Edmunds has been researching the model since the early 2000s and says early college graduates’ postsecondary outcomes can provide a window into increasing attainment for all students.

The model takes care of not only financial barriers, Edmunds said, but cultural ones.

“They might be nervous about talking to their professors,” she said. “They might not manage their time. They might not know how to function independently as a learner.”

When they get one-on-one supports and are introduced to community college campus life, professors, and courses, students feel more prepared and more comfortable.

“When you combine these systems in some way, like the early college does, you’re really minimizing and getting rid of a lot of those barriers,” Edmunds said.

Short-term workforce training key to pandemic recovery

By Molly Osborne

In fall 2019, community college enrollment grew for the first time since the Great Recession. One of the drivers of that growth was an increase in students seeking short-term workforce training.

Short-term workforce training courses are non-degree courses that often lead to an industry-recognized credential or certification. Examples include electrical lineman training, welding, and truck driver training.

For many years, short-term workforce training programs received the short end of the stick when it came to funding. Until 2018, North Carolina community colleges received less state funding per class hour in short-term workforce courses than in curriculum courses. In addition, students cannot use federal Pell grants to cover the cost of these courses.

In October 2019, just as enrollment in short-term workforce classes was taking off, the legislature passed a bill funding them at the same level as curriculum courses — a big win for the community college system and evidence that state leaders recognized the value of short-term workforce training.

Then came the pandemic.

Over the past year, community college enrollment has dropped across the country and in North Carolina. The biggest declines have come in short-term workforce training and adult basic skills courses.

Many of the short-term training courses require hands-on instruction, so they were disproportionately affected when colleges had to move everything online last March. Even when colleges were able to return to in-person learning, they had to reduce the number of students in courses due to social distancing requirements, said Scott Ralls, president of Wake Technical Community College.

The pandemic also disproportionately affected older, nontraditional students who work and have children, whom Ralls said are more likely to be those short-term workforce training students.

Yet national, state, and community college leaders see short-term workforce training as key to pandemic recovery and longer-term economic growth.

“People are thinking about how we can be leveraging short-term training programs for recovery from the pandemic,” said Jeni Corn, director of strategic initiatives at myFutureNC.

Emily Passias, director at Education Strategy Group, says they are seeing this across the country.

“We’re seeing a lot of states and communities thinking about how to best use those stimulus funds that they have coming in and to target towards the sectors where there’s highest employment need and where there’s a reasonable capacity to get the credential quickly [and] get into the workforce,” she said.

Not everyone agrees that focusing on short-term workforce training is going to help people rebound from the pandemic, however.

“A lot of colleges are being driven to short-term programs to help people get a foothold,” said Josh Wyner, co-founder and executive director of Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program. “I worry about that. The data on short-term credentials, outside of healthcare and IT, those short-term credentials by and large don’t confer good wages.”

One effort to help students and colleges identify those short-term credentials that do provide good wages is under way in North Carolina. NC Workforce Credentials, a partnership between the North Carolina Community College System, the Department of Commerce, the NCWorks Commission, the Department of Public Instruction, myFutureNC, and the governor’s office, is working to identify credentials in all sectors that are in demand and lead to family-sustaining wages.

Using labor market data and input from employers, this collaborative working group is creating a list of these credentials to “advise students so that they can make informed decisions, but also equally important as a tool for colleges and education and training providers to be able to make sense of where they should be investing instructional resources,” said Nate Humphrey, associate vice president for workforce continuing education at the North Carolina Community College System.

Within the next year, Corn said, the group hopes to publish the initial list of credentials along with policy and budget recommendations for how to incentivize both colleges and students to invest in these credentials.

“If we had a list of [credentials] we could all say collectively, these are important for the state of North Carolina, then we can start using a combination of federal and state funds … to say we should be pushing people in the short-term training programs for these specific credentials,” Corn said.

Both Passias and Ralls emphasized that in addition to getting people these credentials, states and colleges need to be thinking about how they can create pathways for those same people to further their education.

“It might be sometimes we have to get folks that very first credential, but that absolutely should not be their last credential. Let’s make sure that the wraparound support and the pathways are in place to help folks continue to advance beyond these first short-term credentials that folks are being encouraged to get right now,” said Passias.