What kind of student succeeds at early colleges? Why? Do early colleges really make a difference?

These are questions Julie Edmunds, program director for secondary school reform at SERVE Center at UNC-Greensboro, has been asking since early colleges began to pop up across North Carolina in the early 2000s. With multiple federal grants, Edmunds and her team have been researching the effectiveness of early colleges for over a decade, following a cohort of 4,000 students through their high school experiences and beyond. The SERVE Center has collaborated with researchers from RTI International and RAND Corporation from the beginning.

Their research has found early college students are more likely to attend class, complete courses that prepare them to enter into a UNC-system university, and graduate high school. They have fewer suspensions, earn more college credits while in high school, and are more likely to enroll in a postsecondary institution and attain a postsecondary credential.

The model’s positive impacts are especially important in a state and world where postsecondary attainment is increasingly crucial for success. The very word ‘postsecondary,’ proves, as Edmunds said, that people are used to college coming after high school.

“The early college really is a different model of schooling,” Edmunds said. “It really is high school and college happening at the same time.”

Early colleges create environments for students who might not otherwise go to college and provide rigor and support. They also speed up school, giving students the opportunity to earn two years of college credit or an associate degree for free while in high school. Edmunds said this changes that mindset.

“High school’s not the end,” she said. “And (regular) high school is starting to shift to this, and many high schools in more affluent areas already do this, but the idea is it’s not just about a high school diploma. It’s about what happens after that high school diploma. And early colleges I think, are very good at that, and they were designed from the beginning to assume that students are going to go on to college and to get all those students ready.”

In 2005, Edmunds said she noticed there were more students applying to early colleges than open spots. This was when the model was still brand new, following 2004 legislation establishing the model.

“You know what, here’s a chance to actually look rigorously at what’s going on,” she said.

With the “perfect storm” of interest on both the state and federal level, the research team started convincing early colleges to use lotteries to support her study design. Through three consecutive U.S. Department of Education grants, Edmunds and her team studied 4,000 students from 19 early colleges for 13 years. Findings on postsecondary attainment and success while in college are still coming in as students from the cohort get older. This year, the team was rewarded more funding to look at the model’s impact on employment and earnings.

‘The underserved middle’

The study is rigorously designed and looks specifically at students who are interested in early college. The control group is comprised of students who were accepted through an early college’s screening process but did not get in after a lottery. The experimental group is made of students who passed the screening process and were chosen through a lottery. “The difference is luck,” she said.

Edmunds said she wanted to take other factors that might influence student success out of the equation — to compare students with a similar motivation to try a new environment.

“That kind of design is really important to use when you have a model like the early college because students who choose to attend an early college are going to be different than students who choose not to attend and students who make a decision to go their regular high school,” she said. “And usually those students are going to be more motivated in some way. They’re going to be more interested in going to college, in the experience. So there’s going to be something about the regular high school that didn’t appeal to them, and they want this environment instead.”

The study also included students who got into early colleges but chose not to attend and students who left the early college. About a quarter of students who get in leave for various reasons, including to move, go to a different school, or drop out. Edmunds said this is around the same percentage of students who leave any high school. Students who got into the early college, returned to their regular high school, and then dropped out are still included in the study’s experimental group. This design method, called “intent to treat,” could create more conservative results than what are normally presented by schools, Edmunds said.

“The advantage to [the method] is that it keeps that random assignment intact, and so it makes sure that again there’s no difference except the opportunity to enroll in the early college versus not being able to enroll in the early college,” she said.

Edmunds is clear that she does not think the model is the right fit for everyone. Students who are “high-flyers” academically, have support at home, and fit in socially, she said, will probably do just as well during and after high school from attending a traditional public high school.

“I think of [early colleges] as perfect for that underserved middle, to a certain degree,” she said.

Along with collecting objective data, Edmunds has interviewed students throughout the years about their motivations for attending early college. She would often hear students describe themselves as misfits in middle school.

“Kids who might otherwise struggle to fit in at a regular high school, but who are interested and who are capable of doing the work, but maybe nobody expected them to do it or that kind of a thing. That’s what I see as the population for whom the model can really make a difference.”

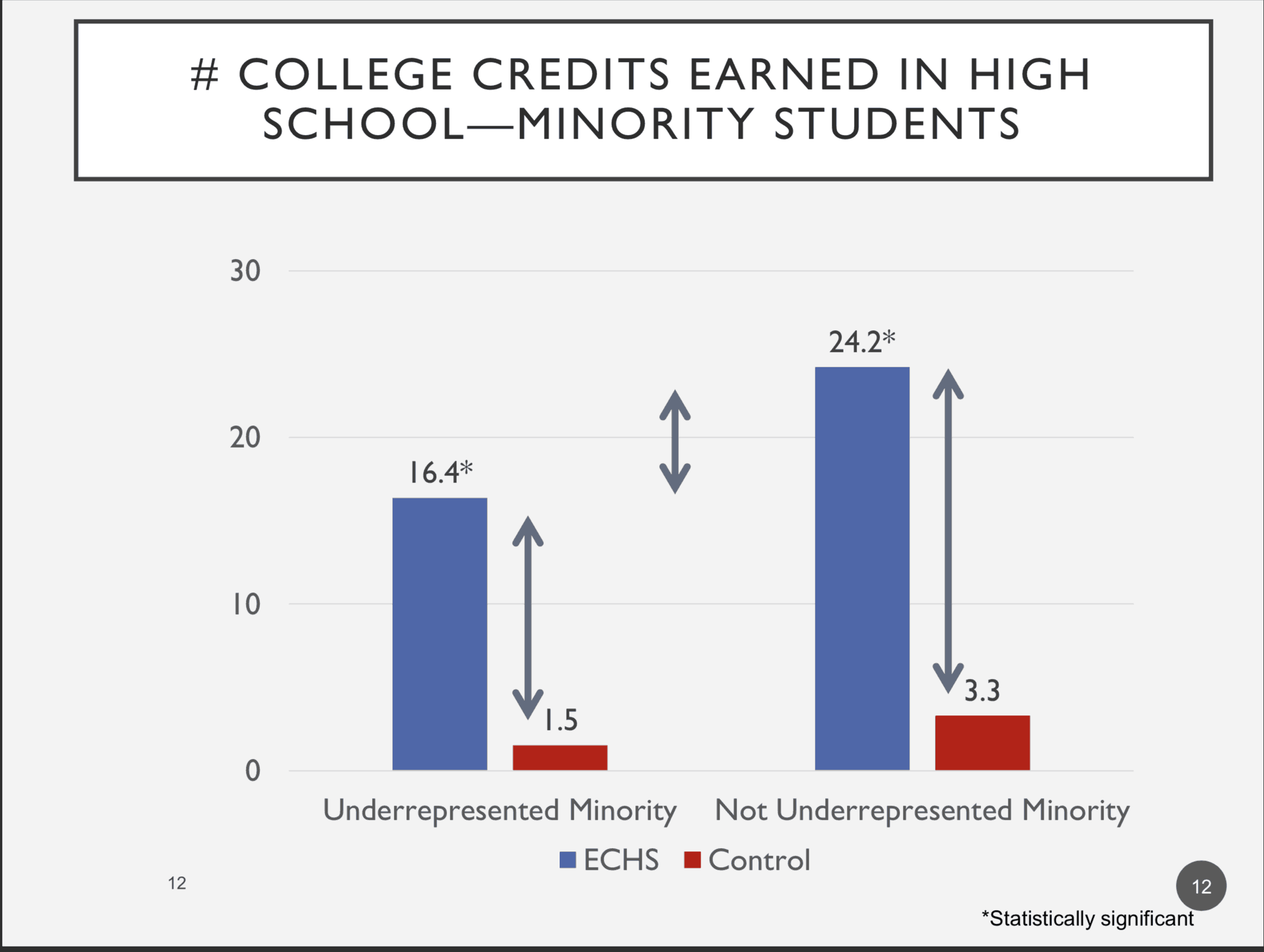

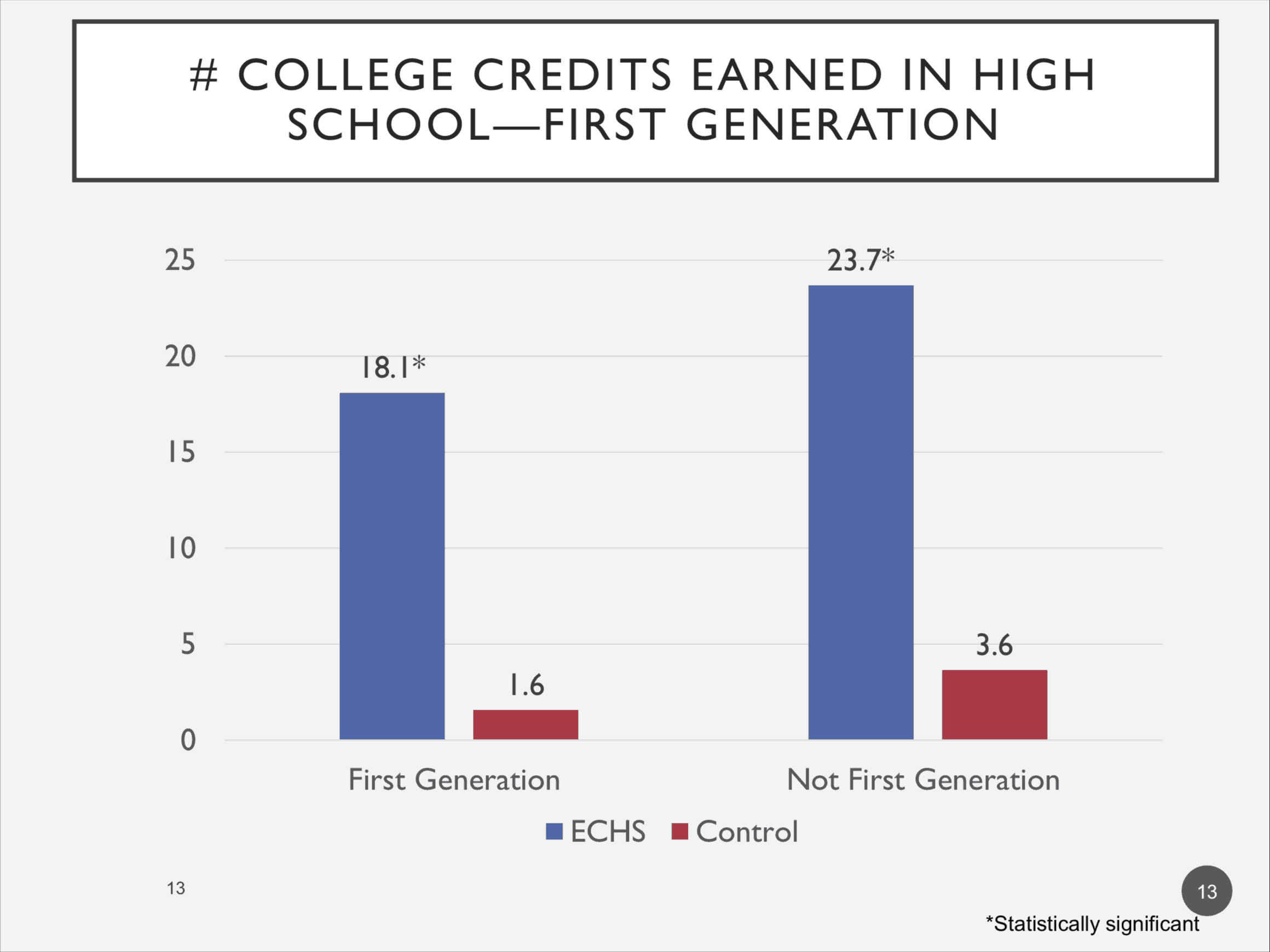

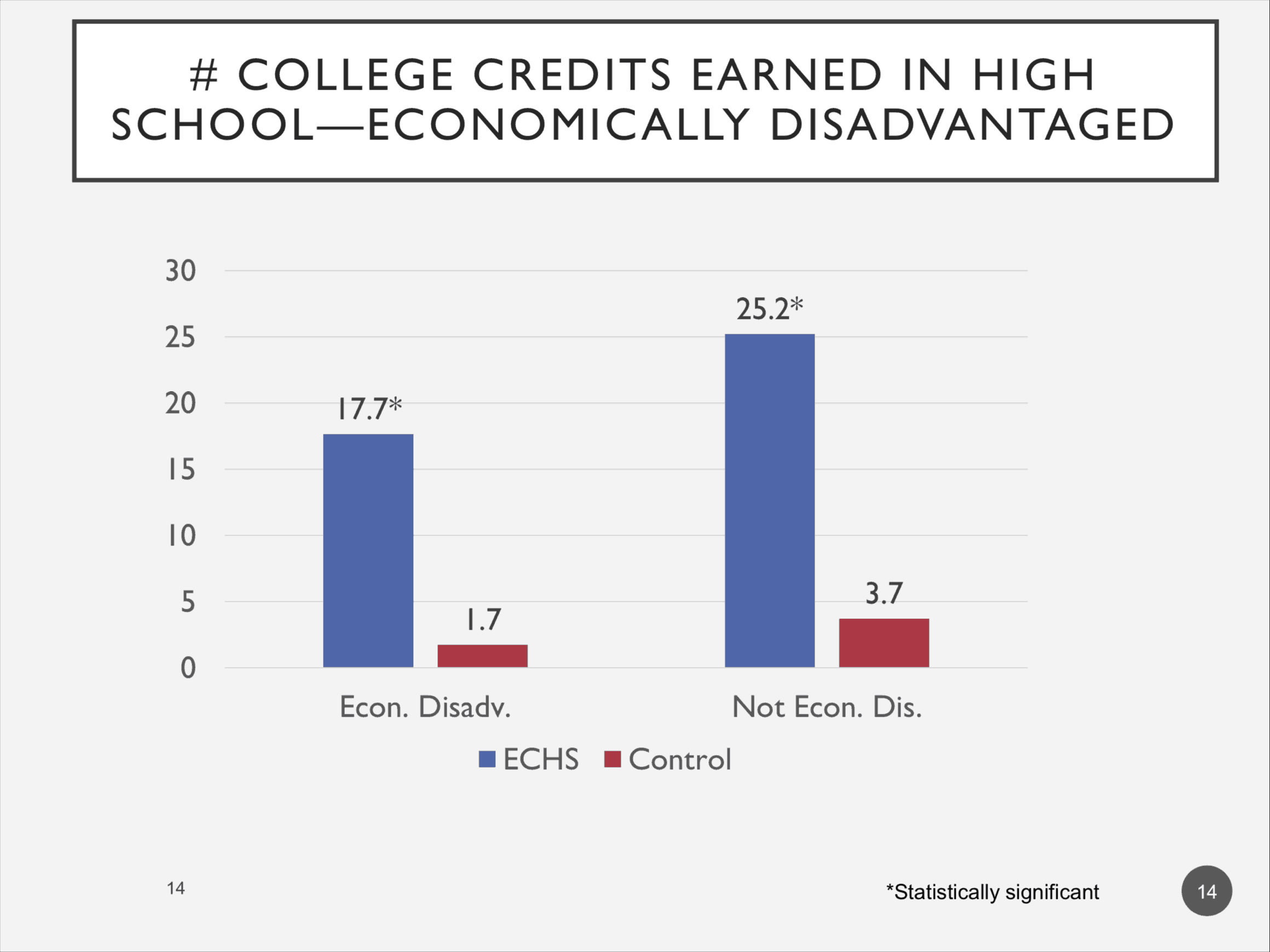

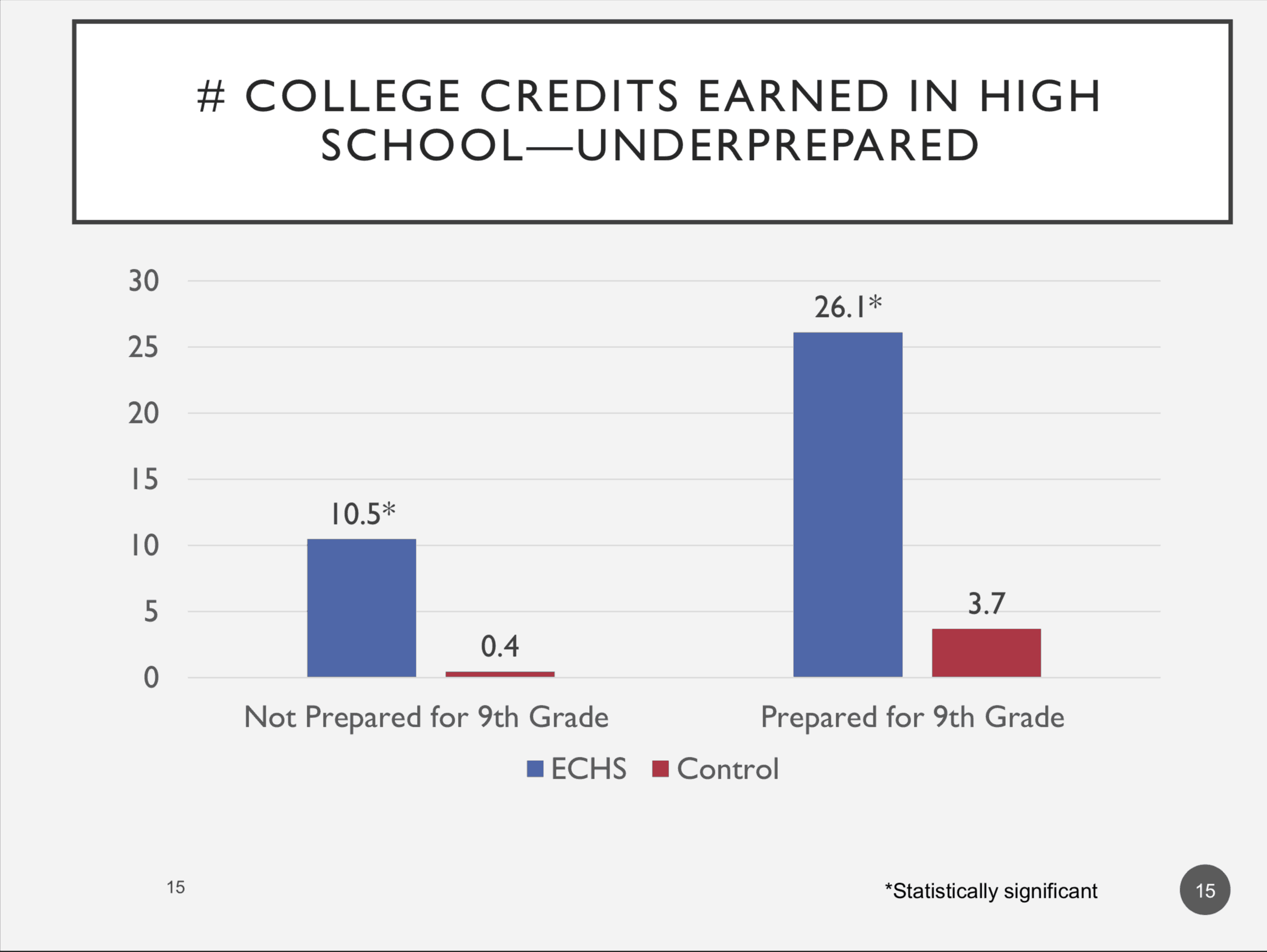

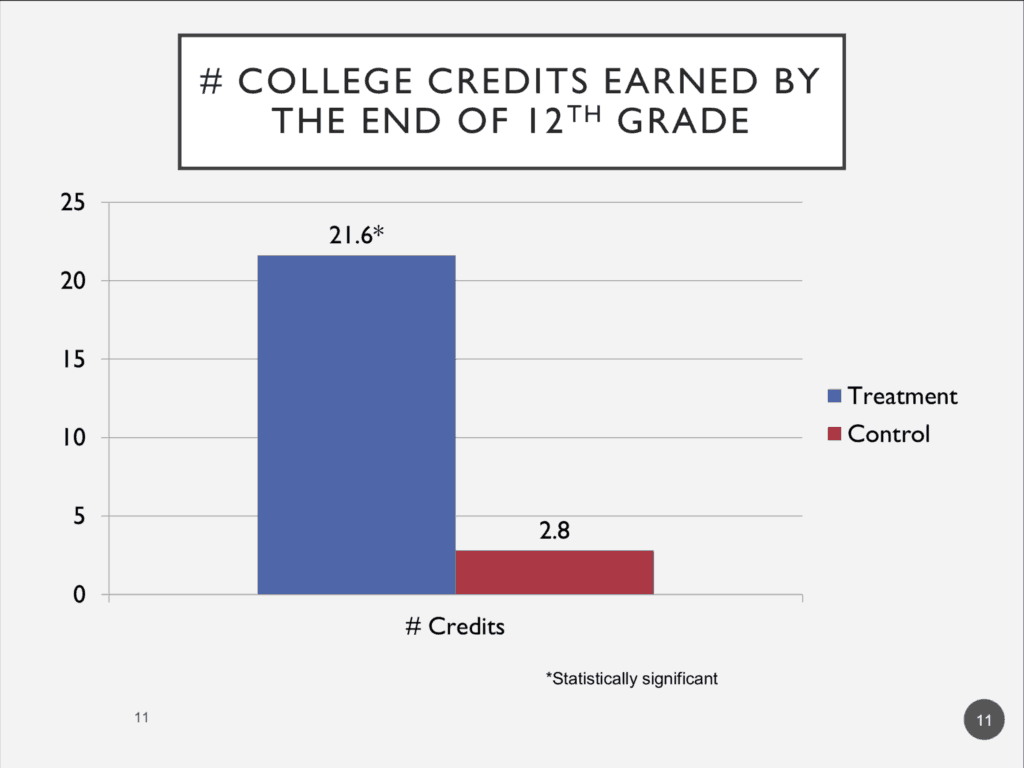

Results

When looking at the number of college credits earned in high school, early college students had more. For the control group of students attending regular high school, this took into account courses earned through dual enrollment and AP (advanced placement) courses, which give students college credit upon passing a final exam. Specific subgroups of early college students also earned more college credits than their counterparts at traditional public high schools, including minorities, first-generation college-goers, economically disadvantaged students, and students who were underprepared in ninth grade.

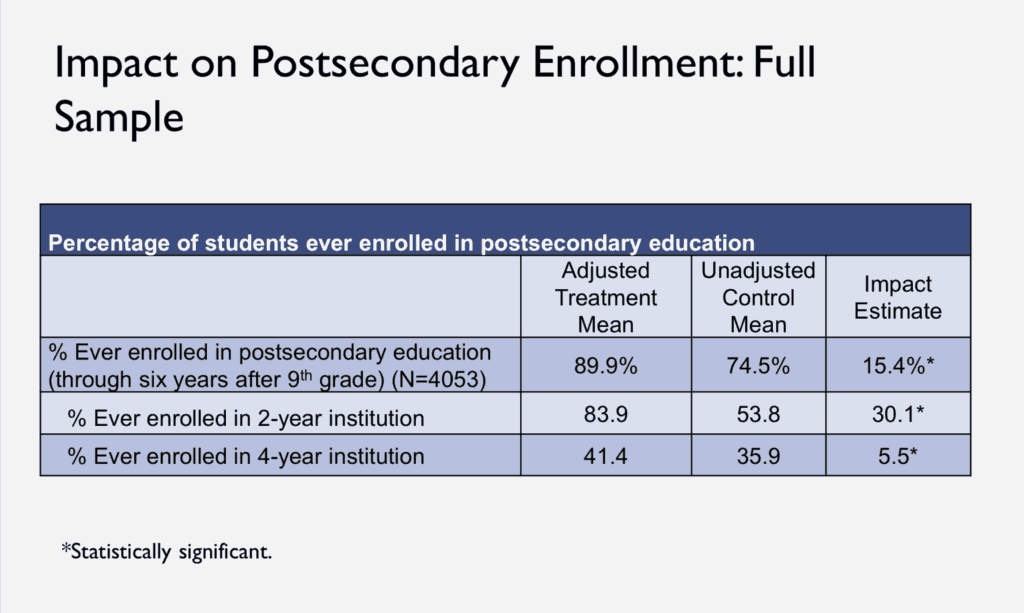

Edmunds and her team also found early college makes a difference when it comes to enrollment in postsecondary education. Though this might seem obvious — early college students must at least enroll in a two-year university — the study waited two years after high school graduation to give students from regular high schools a chance to enroll.

“They don’t entirely catch up,” Edmunds said. Looking at enrollment in a four-year institution after college, early college students are still more likely to enroll than students at traditional public high schools.

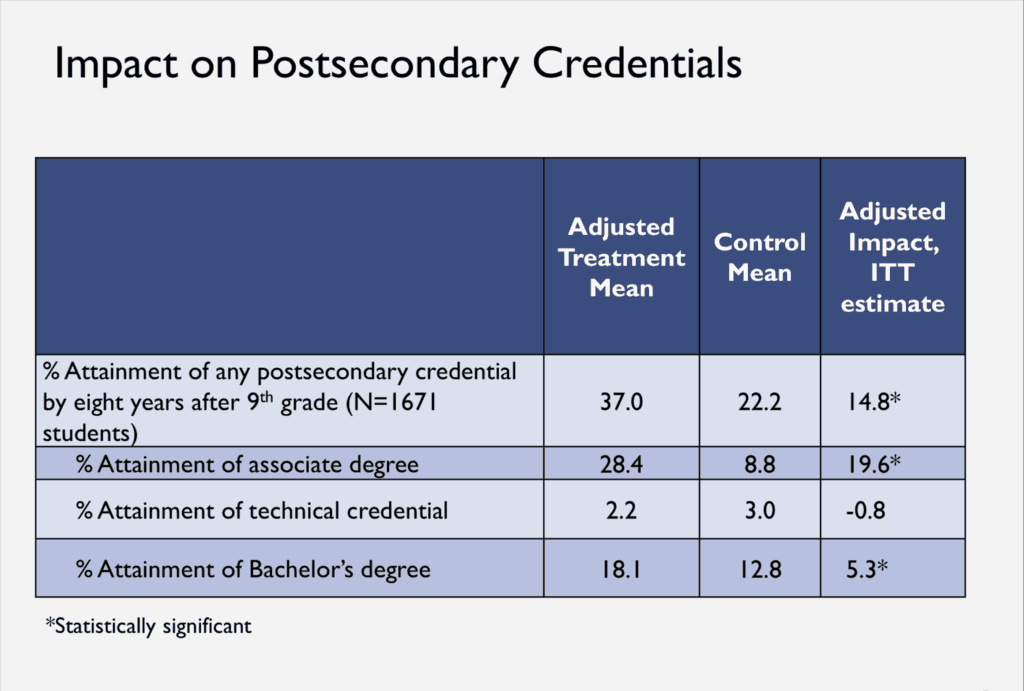

The same positive impact is true for attainment of a postsecondary credential, either while in high school or afterwards. Early college students were found less likely to attain technical credentials than those in regular public high schools, although the result is not statistically significant.

Edmunds also found early college has a slightly positive but not statistically significant impact on students’ GPA while in college. Edmunds writes in a paper submitted for publication in the Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis that this disproves rumors that students may miss core skills through the sped-up process of going to college and high school at once.

“… the acceleration that they received was not counter-balanced by a negative impact on their preparation,” she wrote. Edmunds goes on to write that while early college does not have a statistically significant impact on GPA, it does on postsecondary attainment, including four-year degrees.

“There was also a positive impact, however, on attainment of four-year degrees, which occurred after students left the early college. This suggests that the early college might be providing students with other benefits—beyond increased academic skills—that are influencing students’ likelihood of getting a degree. One possible explanation is that the number of college credits a student receives serves as a form of momentum to accomplish their degree. Another possibility is that early college students have learned more about how to navigate the college system and this is increasing the likelihood that they will attain a postsecondary credential.”

How are early colleges achieving these results?

Edmunds and the SERVE Center team use the phrase ‘mandated engagement’ in a separate research paper published in the Teachers College Record in July 2013 on what parts of the early college model — instruction, structure, relationship — could lead to success. From student anecdotes and surveys, there are a few themes that stand out.

“While some may argue that the schools are not truly ‘mandating’ anything, we make the case that the early colleges are supporting facilitators of engagement at a level that makes it very hard for students not to engage in school. Students in these schools “can’t hide.” Perhaps engagement cannot be legislated, but it is clearly possible to create schools that demand much higher levels of engagement from their students.”

The researchers looked at “indicators of engagement,” like attendance, challenge, work perseverance, and schoolwork engagement. They also studied “facilitators of engagement” like the rigor and relevance of instruction, relationships and expectations between staff and students, and supports like tutoring.

From their analysis, the early college model made a difference on almost every indicator of engagement besides students’ work perseverance. And early college students said they experienced more rigorous instruction, better relationships with teachers, higher expectations from teachers, and more supports.

“When the quantitative results are merged with the interview data, a picture emerges of schools that utilize these facilitators of engagement to create an environment that requires students to be engaged or involved on different levels.”

The researchers aligned these facilitators of engagement with goals early colleges across the state have: preparing students for college (high expectations), powerful teaching and learning (rigorous and relevant instructional practice), and personalization (student supports and strong staff-student relationships).

The examination of the early college model gets at a bigger question of how to open postsecondary opportunities for more students, particularly those who have barriers in their way.

“For me, it becomes an equity issue,” Edmunds said. “Because at this point, the students who are able to go to college are those who already have the advantages. They have parents who already have gone to college in the past. They have incomes that can support them … They have all the sort of cultural capital, social capital, and monetary capital that enable them to take it on. And if the postsecondary education becomes this new default that we expect for everybody, and the only people that are really able to take advantage of that are people that already have advantages, well then what does that mean? That means that our gap continues to widen.”

Edmunds said the model also allows for somewhat of a clean slate. Traditional public high schools have had layers of strategies and programs put on them for ages, with different aims as society has shifted priorities. Early colleges were able to be intentional about their goals and align every part of their schools around those goals from the beginning.

To have a plan for every student starting in ninth grade and earlier is necessary, Edmunds said. All high schools, she said, should be shaping a student’s experience with some sort of postsecondary attainment in mind, whether it’s a workforce-applicable credential, an associate degree, or earning general education requirements for a four-year institution by graduation.

“If this is our new default, we need to think about schooling in a way that addresses that and makes it the new default for everybody in some way.”

Editor’s Note: This article was updated to include that researchers at RTI International and RAND Corporation collaborated with UNC-Greensboro’s SERVE Center to study North Carolina’s early college model.