As North Carolina’s public schools navigate another week of remote learning, questions around ensuring digital equity for all students are still front-of-mind for many.

How can a district equip all students with the devices necessary to engage in digital remote learning? And then, what does it take to ensure that every student has the internet access needed to use that device?

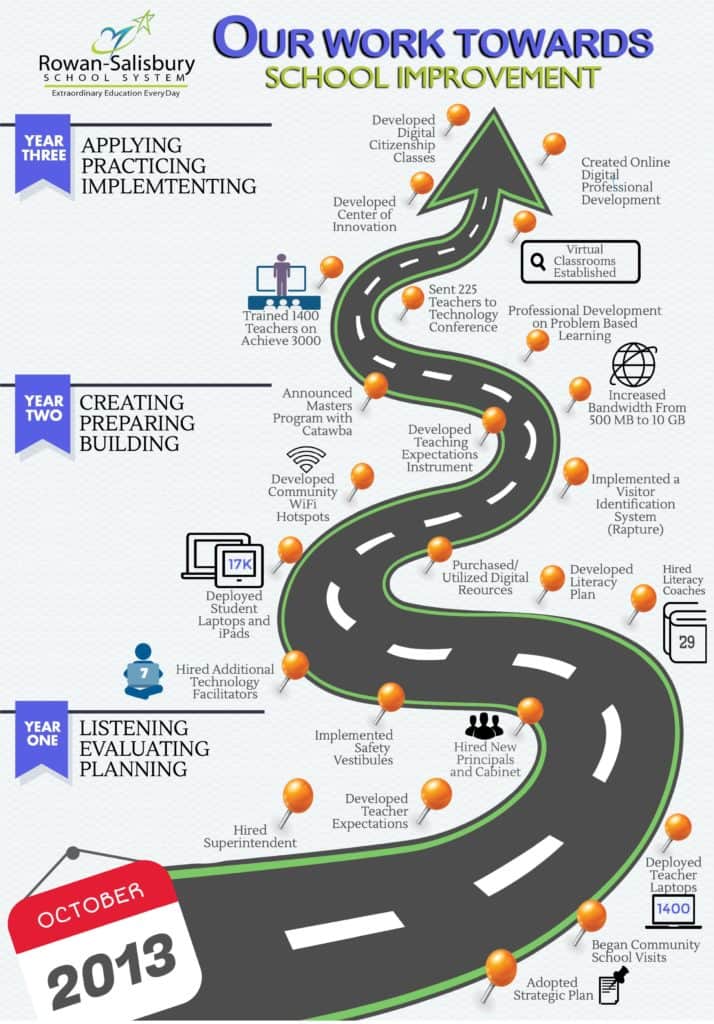

Rowan-Salisbury School System, a district located about an hour north of Charlotte with 34 schools and about 20,000 students, offers one example of how to tackle the digital divide.

Rowan County, North Carolina

– Broadband subscription rate (households with a DSL, cable or fiber-optic subscription): 62.94%

– Households with no internet access: 22.5%

– Households with no computer devices: 16.46%

Data source: NC Department of Information Technology Broadband Indices, which pulls from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2013-2017 American Community Survey.

A device in every student’s hands

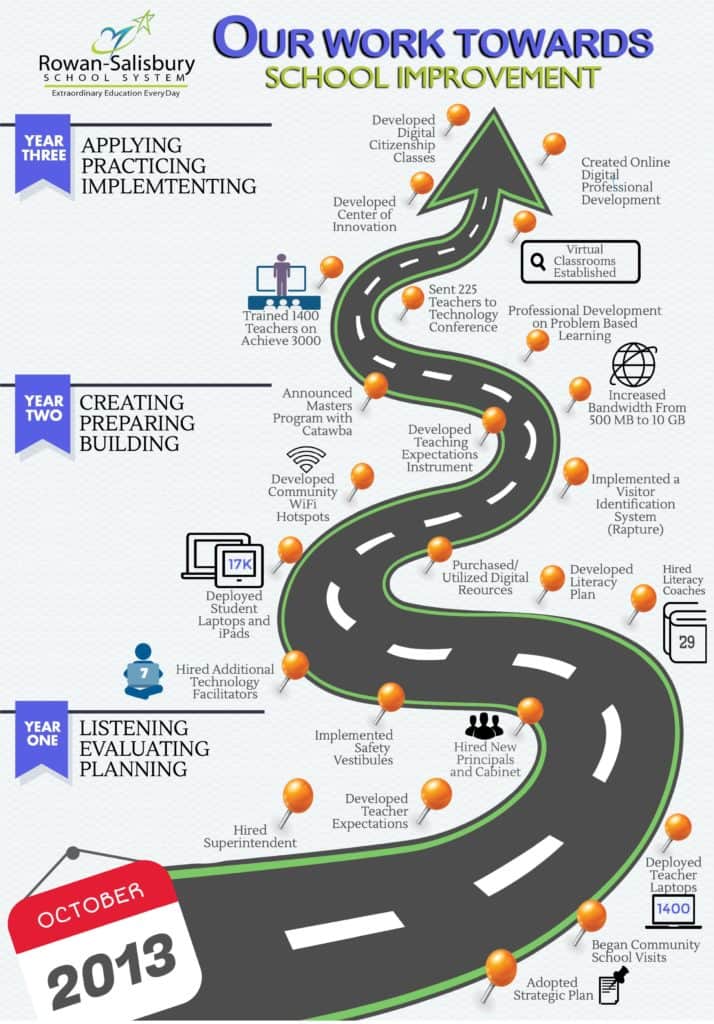

In the fall of 2013, Superintendent Lynn Moody arrived at Rowan-Salisbury Schools after a tenure as superintendent of a district in South Carolina.

Andrew Smith, the district’s chief strategy officer, recalls that it was “immediately known that she was a woman of innovation.” Moody was known for her work in South Carolina around one-to-one – or providing a device for every student – and she brought a similar mindset toward the value of technology with her to North Carolina.

In April of 2014, Moody took a team of district staff and principals to visit Apple’s Executive Briefing Center in Reston, Virginia. Smith said this trip quickly made it clear what the potential impact of a one-to-one program could be on education.

“By the time we got home from Virginia, we had a plan drawn out,” Smith said. “And we began the process of talking to our various stakeholders – to parents, the teachers, to principals, and students as well, about what it might look like to go one-to-one.”

From there, things moved quickly. By June of the same year, the district’s technology lease with Apple was approved. The lease structure allows for incremental payments over three years to make the devices more affordable, and the district also participates in a buyback process to ensure they have up-to-date technology.

But the effort wasn’t without pushback. According to Smith, the notion of putting technology in the hands of every student made some in the community anxious – and the district had to convince people that the price tag on the initiative, to the tune of $14 million, would have value.

“It was a challenge. We had to convince our board members. We had to convince our county commissioners because of the way the lease structure was developed,” Smith said.

After the lease was executed, teachers received devices within a month or so, and students received devices when they returned to school in the fall of 2014.

Addressing the connectivity issue

Devices are often only as good as the internet connections to which students have access. As students in grades 3-12 began bringing their devices home every day, the need to address internet access became immediately clear.

“We realized about as soon as we began the one-to-one lease process that we were going to have to try to mitigate who had internet and who didn’t,” Smith said.

Around the same time that the district was shifting to one-to-one, something else happened – Salisbury, the county seat, earned the title of the “city with the fastest Internet in the U.S.” According to WFAE, Salisbury used $33 million in bonds to commission the creation of its own fiber network.

But just 10 miles down the road, in a rural corner of the county, you would find internet deserts.

“It wasn’t that the people couldn’t afford it. It was that internet did not exist in that space,” Smith said. “What do you do when you have a divide where you have the fastest internet in America and no internet? And that question mark really drove, alongside the notion of socioeconomic status, how we were going to help kids.”

Moody decided to launch a campaign around two issues – literacy and connectivity – and the district started a series of annual literacy summits. From the first of those summits, held in September 2014, came a challenge to establish 100 community Wi-Fi access points.

“We went out to businesses and to local municipalities and basically said, ‘We’d love for you to partner with us. All these kids have devices. Can we find a way for you to offer internet?'” Smith said.

The district also turned to another anchor institution – local churches – to establish homework hot spots that students could access after school. The district’s technology department assisted the initiative by helping churches think through specific network infrastructure needs.

At the peak of the initiative, Smith said there were roughly 75 Wi-Fi access points spread across the county. Participating businesses hung window clings denoting that they partnered with the district and provided free Wi-Fi for students.

The district was also able to provide hundreds of mobile hot spots directly to students through funding from Communities in Schools.

While these partnerships were unique, Smith acknowledged they didn’t solve all the connectivity problems.

“I describe our process as really kind of a patchwork. Because unless you give every kid 5G connectivity to the device, even then, satellites don’t go everywhere. So it’s challenging,” he said.

Shifting strategies amid COVID-19

As soon as school buildings closed due to COVID-19, Rowan-Salisbury School System worked to gather data from students on what their internet situation looked like at home. Was their connection high-speed? Were they only able to access the internet using data on their cell phone? The results of the survey helped the district identify the biggest gaps.

Through a partnership with the 1Million Project Foundation, Rowan Salisbury Schools System has access to hot spots that can be distributed to high school students. The district decided to identify which high school students lived in households with younger siblings who could also benefit from the hot spots and distributed them to those households first.

Then, due to the nature of having multiple telecommunications providers across the county, the district began purchasing hot spots from different providers and sending technicans out in the field to determine which worked best in what areas.

“It does no good to send a hot spot off to a student if there is no service,” said David Blattner, the district’s chief technology officer.

And it’s not just students – some teachers in the district live in areas with few or no internet service providers, making it difficult or impossible to provide remote instruction. The district worked quickly to get every teacher a hot spot with robust enough connectivity to support full days of remote teaching.

Advice for other districts

Robust professional development

“Looking back, all this wasn’t really possible without a really robust professional development plan,” Smith said.

The district spent a lot of resources to ensure every school had an instructional technology facilitator to guide the work around using devices in education. Professional development around things like developing high-quality lessons using technology was crucial – especially since the pace of change was so rapid.

Reflecting on the switch to remote learning now during COVID-19, Smith said: “We are able to go to remote learning so quickly because we’ve been doing it for so long, and that was a product of lots of professional development over the years.”

The pace of change

“Because of the political nature of a one-to-one lease, you really have to strike when the iron is hot,” Smith said. “I think if we could have done it over again, we would have probably tried to slow down some the roll out.”

Smith said the district might have been one of the fastest to ever go from “nothing to everything” when it comes to one-to-one – it took about six weeks for them to pull it off. That meant that teachers had to learn really fast. In retrospect, if political strings hadn’t been at play, Smith thinks the district would have tried a more phased approach that eased people into it.

“Just the sheer change management processes that have to go into moving an organization like that takes time,” Smith said.

Communicate your ‘why’

“During some of the really challenging times of the one-to-one, we had to remind ourselves why we were doing it. We had to remind our community of our ‘why,'” Smith said. “You can’t spend enough time telling people that.”

There was some opposition to the initiative when it began, but Smith said when people hear the reasons behind why the district is doing it – to help bridge the digital divide and ensure all students have access to current, relevant information – they understand that.

And after a while, Smith said that it’s easy to become complacent and forget to continue communicating that “why” to community members.

“So staying grounded in that and making sure to get it out there and keeping the community educated is something to not lose as you’re going along,” he said.

And all the other dos and don’ts

At a conference in 2015, Smith gave a presentation titled “Do THIS, not THAT,” and it’s filled with insight into how the Rowan-Salisbury team navigated decisions and processes throughout their one-to-one journey.

The do list includes: start with research, secure buy-in from the top down, start with “Why?,” create a digital conversion team, change your learning spaces, involve parents, and more.

And the don’t list includes: forget the community ecosystem, forget to build partnerships with vendors, confuse wireless coverage with wireless density, underestimate location, overlook the details, forget to change Board of Education policy, and more.

Read the full presentation below.