It has been almost two months since Gov. Roy Cooper first closed all K-12 North Carolina public schools due to COVID-19. Since then, one topic has stayed front-of-mind for many — broadband internet.

As North Carolina’s 1.5 million public school students navigate remote learning, households without broadband internet are left behind. A presentation to a House working group in the General Assembly by Jeff Sural, director of the state’s Broadband Infrastructure Office, recently estimated the state’s homework gap — or the number of households with a student living in them but without internet access — at 197,139.

On Monday, May 4, UNC-TV and ncIMPACT hosted a virtual town hall on the digital divide. Anita Brown-Graham, director of ncIMPACT, moderated a discussion about how COVID-19 affects broadband challenges and solutions in North Carolina communities — for students learning at home, adults working remotely, individuals receiving health care via telemedicine, and small businesses and employees applying for benefits to support them through this crisis. Watch the full event below.

Guests on the town hall included Sonja Gantt, executive director of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools Foundation; Bruce Clark, executive director of Digital Charlotte; and Patrick Woodie, president of the NC Rural Center.

Gantt said the COVID-19 pandemic shifted internet access for students from nice-to-have to a necessity. While Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS) provides devices for every student in grades four through 12, many don’t have internet access in their home. Those students may have previously relied on community centers and libraries to get their homework done — facilities that are now also closed.

“It really put a new emphasis on, we’ve got to do something about it if we want our children to take advantage of the learning that’s being offered online,” Gantt said.

According to Gantt, E2D, a nonprofit focused on digital inclusion, helped CMS find a deal for mobile hot spots. Then, the CMS Foundation and other donors stepped forward to provide 6,000 hot spots to CMS students who didn’t have connectivity at home.

While mobile hot spots and Wi-Fi on school buses are providing short-term solutions to connectivity during COVID-19, the panelists acknowledged that a long-term solution is needed. When asked to predict how long it will take for every North Carolina student to have home internet access, Clark said three to five years.

“It’s at the will of the leadership and businesses in our state to make the decisions to ensure that everyone has access in their home,” said Clark. “And not just any access — but access to broadband, high-speed internet — so they can take advantage and participate in our modern society, economy, and democracy, and educational system.”

For Woodie, bridging the digital divide requires a focus on three A’s — access, affordability, and adoption. Many rural areas lack the infrastructure that provides broadband access. But in areas where broadband access is available, that doesn’t make it affordable — Woodie said many families can’t foot a $60 or $70 bill every month for broadband. And then there’s the issue of adoption — making sure individuals understand the usefulness of connecting to and utilizing the internet.

Brown asked about families who live within a mile of known broadband access yet aren’t eligible to subscribe. Woodie said this is a problem he hears about often, and that it illustrates the importance of having competition among multiple providers in any given area.

Through a combination of support from U.S. Department of Agriculture ReConnect grants and state support from the Broadband Infrastructure Office’s GREAT grants, Woodie said there was more construction of last-mile broadband in North Carolina before the pandemic began than at any other time in the state’s history.

“The reality for rural communities is they are low density — that makes the business models for making a service that will pay for itself a greater challenge,” said Woodie. “We have to subsidize the construction of this infrastructure in order for it to be in place. And what we have are the tools that are making it work at the federal and state level.”

Woodie was clear that every corner of North Carolina needs the infrastructure for broadband internet access, but he said we also “have to be agnostic about the technology,” and that last-mile fiber to every home or business in the state wouldn’t be possible or affordable. That means a mix of technologies will be needed, including high-speed fixed wireless solutions. Woodie said there are a lot of small companies willing to step up and offer these types of mixed solutions, and that those approaches should be encouraged.

As an example of addressing home internet access in rural communities, Woodie pointed to Rutherfordton, a town in western North Carolina with a strong tourism economy. He said that the town decided it wanted to install a Wi-Fi network to serve the downtown area as a benefit to visitors. Officials sat down and mapped out homes where students at the local elementary school lived to ensure that every one of those houses was also covered by the free network.

“Speed may be an issue, but we need to be creative in thinking about the variety of ways that we can make access available, affordable, and sometimes free,” said Woodie.

While there is no shortage of challenges to consider when it comes to offering broadband internet to every household in the state, Woodie remains optimistic because of the bipartisan support this issue receives.

“I think it’s a sign of progress and a sign of the possibilities that lie ahead of us,” he said.

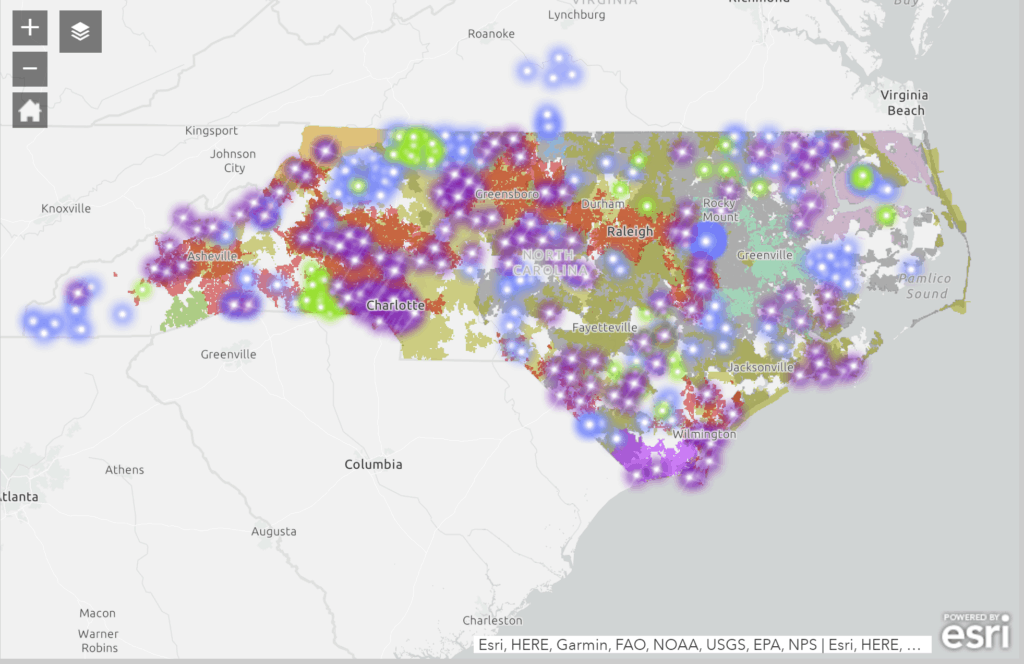

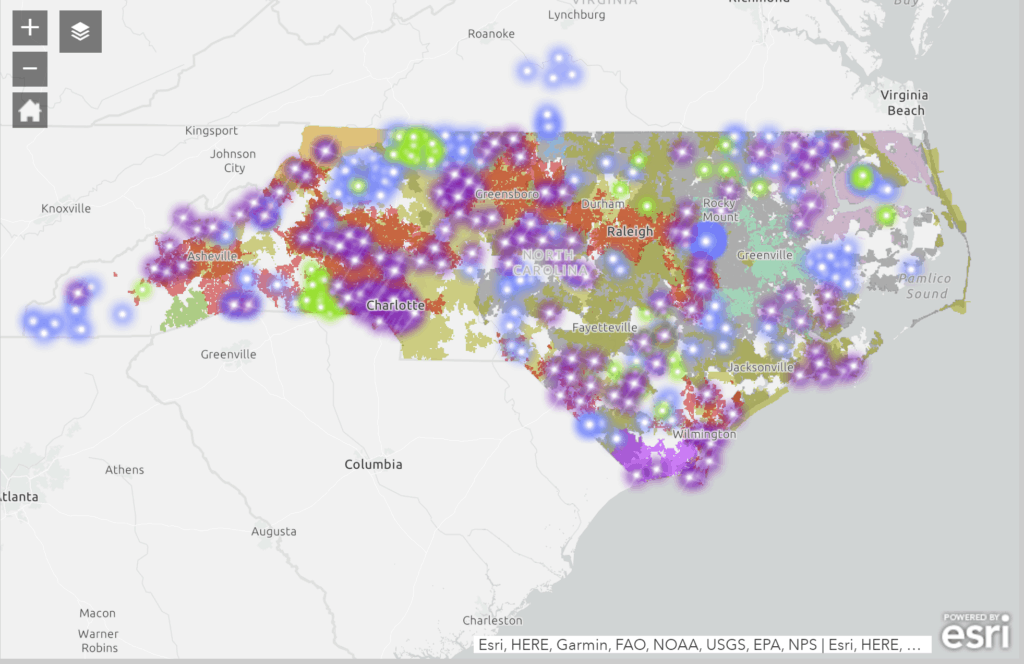

Look up the broadband subscription rate for your county

The following data lookup tool is populated with data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2013-2017 American Community Survey (ACS). Type in the name of any North Carolina county to see its broadband subscription rate, which is the percentage of households with a DSL, cable, or fiber-optic subscription.