Available fund balances at most North Carolina school districts are lower than they were in 2013, according to the most recent data from the Local Government Commission (LGC).

A combination of factors contributed to this trend, including: the lingering effects of the 2008 financial crisis, a decline in population and increase in students attending charter schools, rising costs of benefits, and less funding flexibility for school districts. Local variables particular to each district also likely contributed. All of these factors have played a role in declining fund balances and set up the perfect storm now that districts are facing the COVID-19 pandemic.

The LGC — a commission within the state treasurer’s office — annually collects fund balance data for all state school districts. The most recent data for 2019 shows that 87 school districts have lower available fund balances than they did in 2013. Only 26 have a higher available fund balance.

Here’s the data for 2009, 2013, and 2019. Take a look.

So what is an available fund balance? And why does it matter?

Fund balances

If you have $5,000 in your bank account, after you pay your current expenses, you don’t want that balance to drop to zero. Whatever money is leftover in your account after you’ve paid for everything is the available fund balance. That’s my description. The Local Government Commission described it as being “essentially the equity in the Local Current Expense Fund,” according to an email from a spokesperson there.

Think of it as a rainy day fund. In the email from the LGC, the group said that the available fund balance “is a savings account that schools can use” if unanticipated expenses or opportunities pop up.

The money in these fund balances is local money, money the districts get from their county commissioners. It is not the cash they get from the state or federal government. However, money districts get from the state or federal government can make an impact on how much of their fund balances districts end up spending or saving.

Philip Price, the former long-time Chief Financial Officer for the State Department of Public Instruction, said that good practice is to keep a minimum of 8% of yearly expenditures in a school district’s available fund balance. That’s about one month worth of expenses.

But the LGC said that’s not necessarily true. They said the 8% rule doesn’t apply when it comes to parts of the government that can’t levy taxes – like schools. Instead, the Local Government Commission recommends that districts have an agreement with their county about how much their fund balance should be.

This is because some counties might be more willing to give schools funds when they need it for emergencies. If that’s the case, the school district may not need as high of a fund balance. Alternatively, some counties are less willing, and in that case, districts would need a higher fund balance.

Ricky Lopes said that relying on the county can be a tricky proposition for school districts. He was chief financial officer at Cumberland County Schools for 26 years until he retired in 2015.

“If all 100 counties had a good relationship with their county commissioners … they could rely on them to provide the funds,” he said. “Unfortunately, that’s not the case in the real world.”

In 2019, there was a wide variation in what percent of yearly expenditures districts kept in their available fund balance. For example, Rockingham County Schools had 99.56% and Thomasville City Schools had -15.5%.

In total, 28 of the state’s 115 school districts had an available fund balance that was less than 8% of their yearly expenditures in 2019. In 2013, that number was 12.

What happened?

So, why are fund balances lower in 2019 than in 2013? Let’s start with one obvious possible culprit: the 2008 financial crisis.

Looking at data from 2009, we see that fund balances were even lower than they are now. Sixty-eight districts had a higher fund balance in 2019 than in 2009. Only 26 school districts have a higher fund balance now than in 2013.

But the rebound from 2009 to 2013 was thanks, in part, to funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) pouring into North Carolina from the federal government to deal with the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis, according to Lopes.

He said the money was coming in from the federal government in a roughly three-year cycle, which could explain why, by the time 2013 rolled around, a lot of fund balances were doing better, at least somewhat. Instead of spending their own money, districts could use federal funds for some items, Lopes said. So they were able to shore up their fund balances with those local dollars.

Price said there were a lot of ways districts could use the federal funds to increase their fund balance, including covering capital costs they would have originally paid for locally. Here is a document that covers the uses of the stabilization funds.

So the infusion helped for a time, but then the federal money stopped.

And the impacts of the financial crisis lingered. School districts faced a decline in resources. They expected that things would rebound and didn’t true up their budgets to face the new fiscal reality. When cuts weren’t restored, they had to dip into fund balances to make up the difference.

All of that could explain, in part, why from 2013 to 2019, the fund balances slowly dwindled.

“Most districts have not recovered from that yet,” Lopes said. “Because what they did lose, they haven’t gotten back yet.”

Another contributing factor is state funding. While overall state appropriations increased from $7,506,553,067 in 2012-13 to $9,546,315,927 in 2018-19, spending priorities changed.

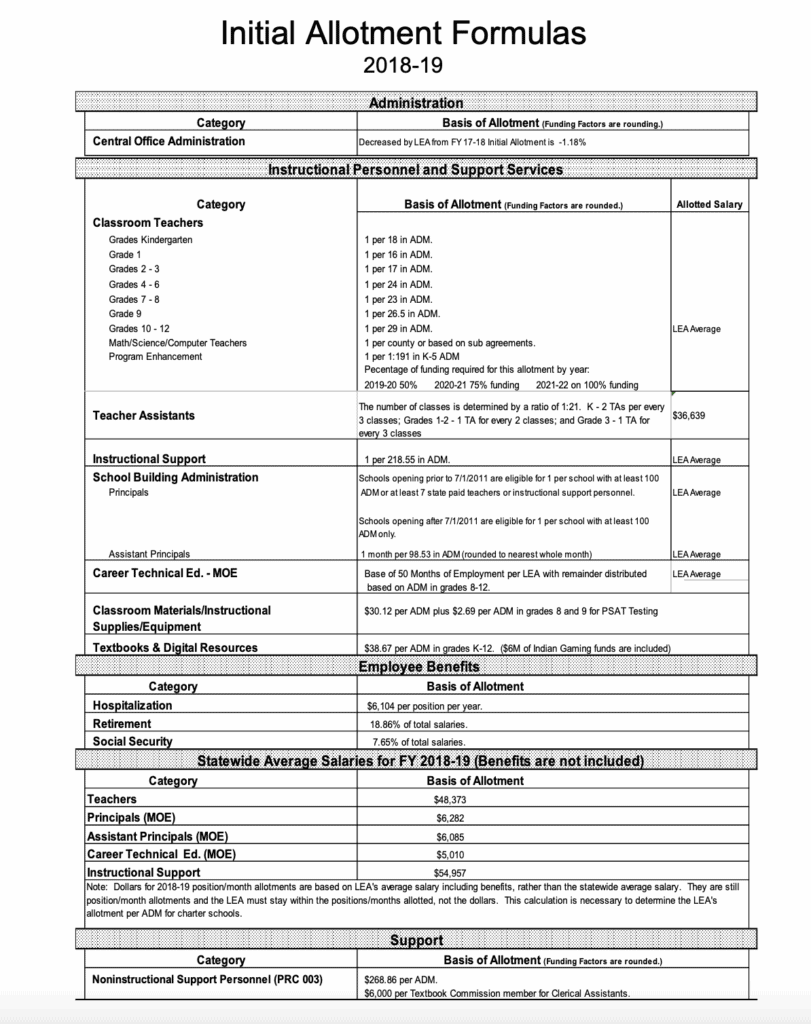

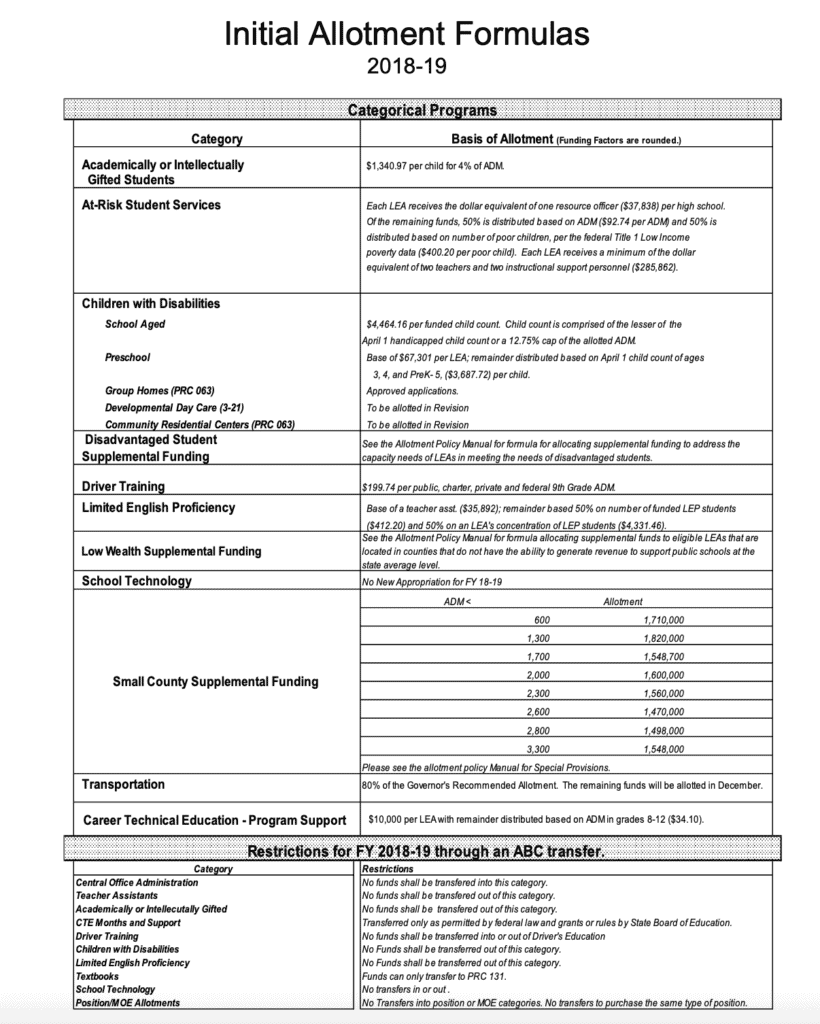

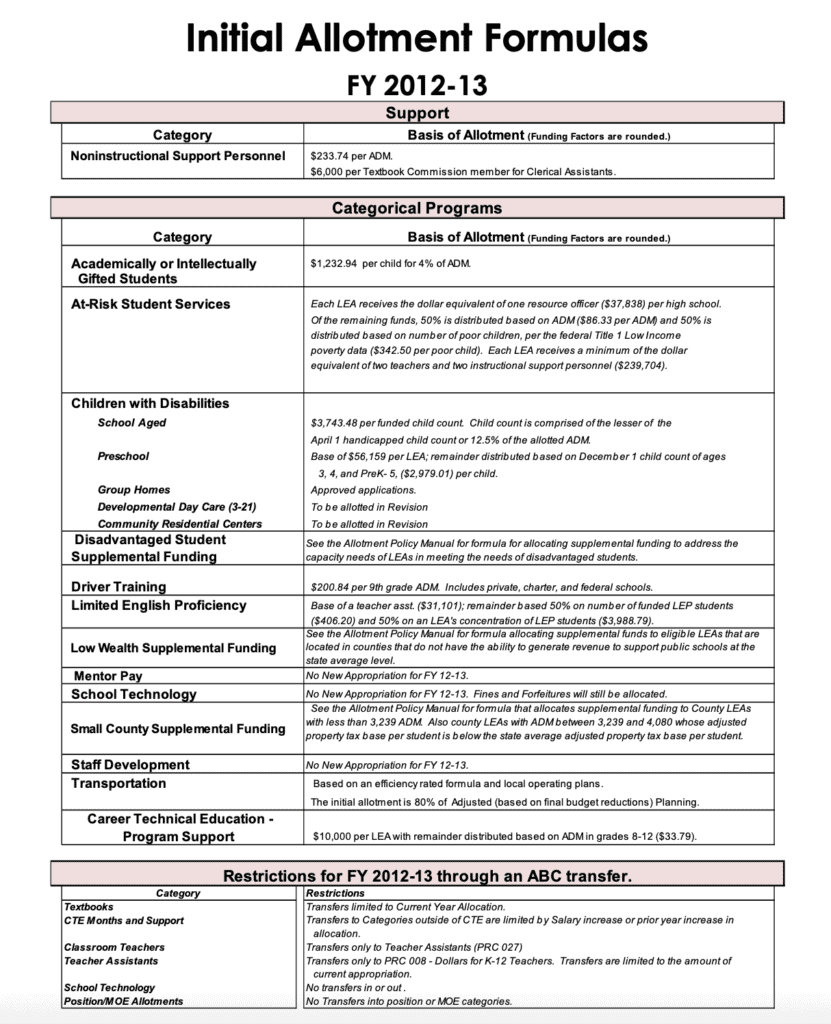

Here is the data on funding formulas for various items from the 2019 highlights of the North Carolina public school budget on the state Department of Public Instruction’s website. These are the formulas used to determine how much money school districts get from the state for different items.

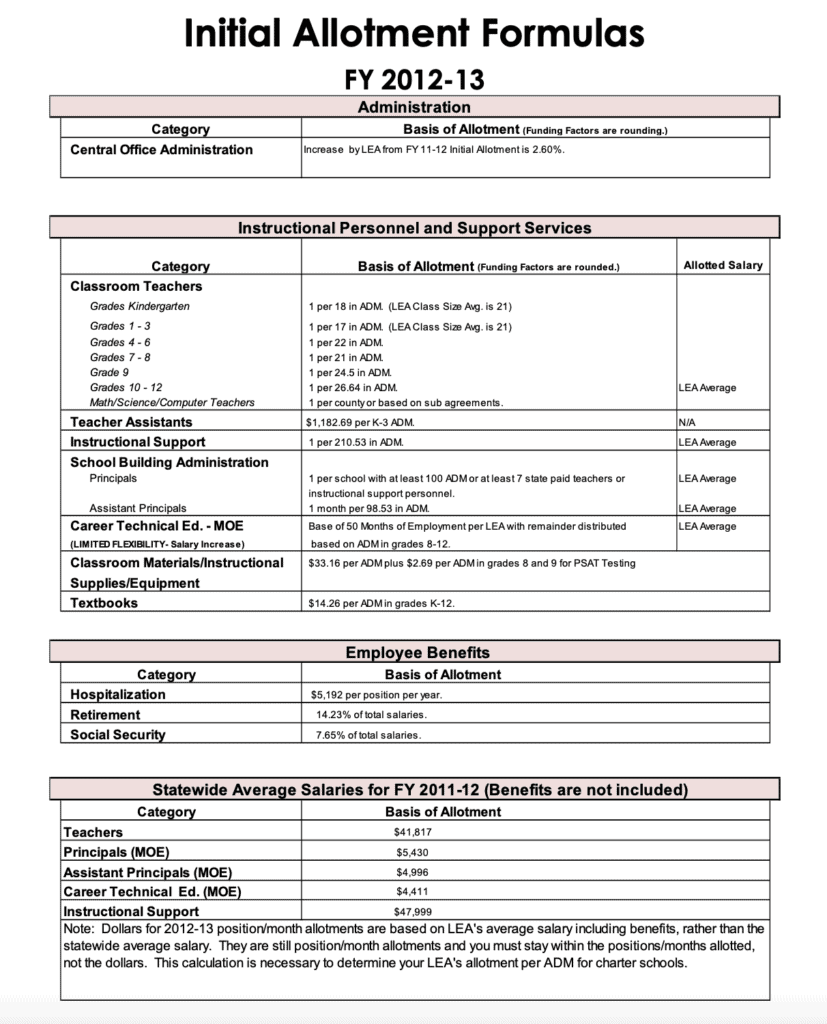

And here it is from 2013.

“You wouldn’t believe how many school districts got into trouble because they never reduced staff,” Price said, referencing teacher assistants in particular. “They thought the state was going to restore the funding.”

You can compare the documents above to see various line items where the formulas have changed, leading to decreased resources for schools.

There were increases, too. For instance, average salaries are higher now than in 2013, as is the funding for academically and gifted students, students with disabilities, and at-risk students.

The formula for textbooks and digital resources appears to have gone up since 2013. But if you go back a little further, you see a different story. In 2019, the formula for textbooks was $38.67 per average daily membership in grades K-12. That is definitely up from 2013 when it was $14.26. But both of those numbers are dwarfed by what the formula was pre-recession in 2007. Back then, just for textbooks, schools got $65.43 per average daily membership. And in 2019, the line item is for textbooks and digital resources – not just textbooks as it was in 2013 and 2007.

With decreases in some line items, districts may have had to dip into their fund balances to maintain resources where they thought they needed to be.

Something else that has gone up is the price of retirement and health benefits, and districts are responsible for covering that for locally-employed staffers.

In 2019, retirement was 18.86% of total salary and health benefits were $6,104 per position per year.

Back in 2013, retirement was 14.23% and health benefits were $5,192 per position.

But if you go back to pre-recession times – 2007 – the numbers are even starker. Back then, retirement was 7.14% of total salary and health benefits were $3,854 per position.

Small school districts are particularly hard hit, Lopes said.

“Even though they don’t have as many local employees, the ones they do have, they have to pick up the higher percentage,” he said.

And there may be an even bigger culprit for lower available fund balances: declining population.

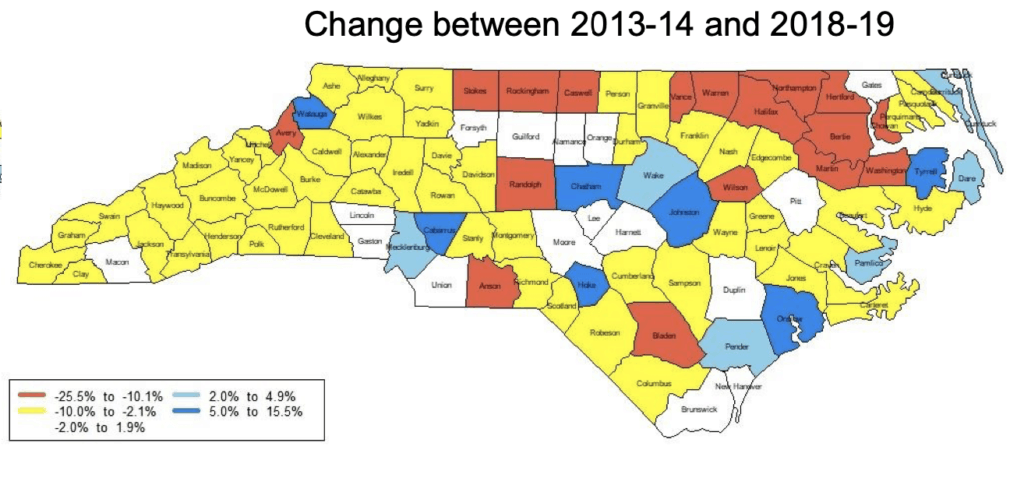

The population in counties around the state has been steadily dropping since 2013. Fewer people means fewer students. Fewer students means less money from the state.

Here’s a map that shows population change. Red, yellow, and white are areas where the population is dropping or barely increasing. Light blue and dark blue are areas where it is increasing.

Population doesn’t decline in such a way that a school loses 20 third graders. Instead, a school may lose 20 students, but just a few from each grade. That means that they still need the classrooms and the teachers – they just have fewer students and less money from the state. Their allocation is shrinking while their costs remain the same. This may necessitate local funding to make up the difference, and thus, a dip into the available fund balance.

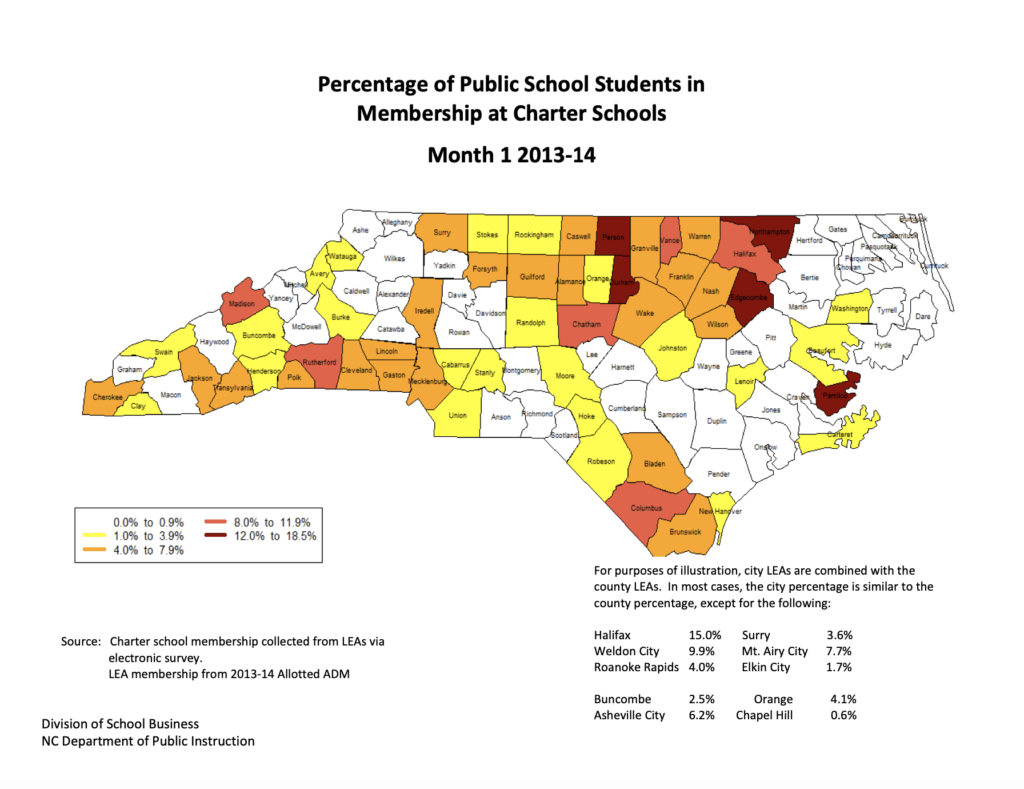

At the same time, the percentage of students enrolling in charter schools has grown since 2013. Look at the map below. White indicates areas where little to no students are in charter schools. There’s a lot of white.

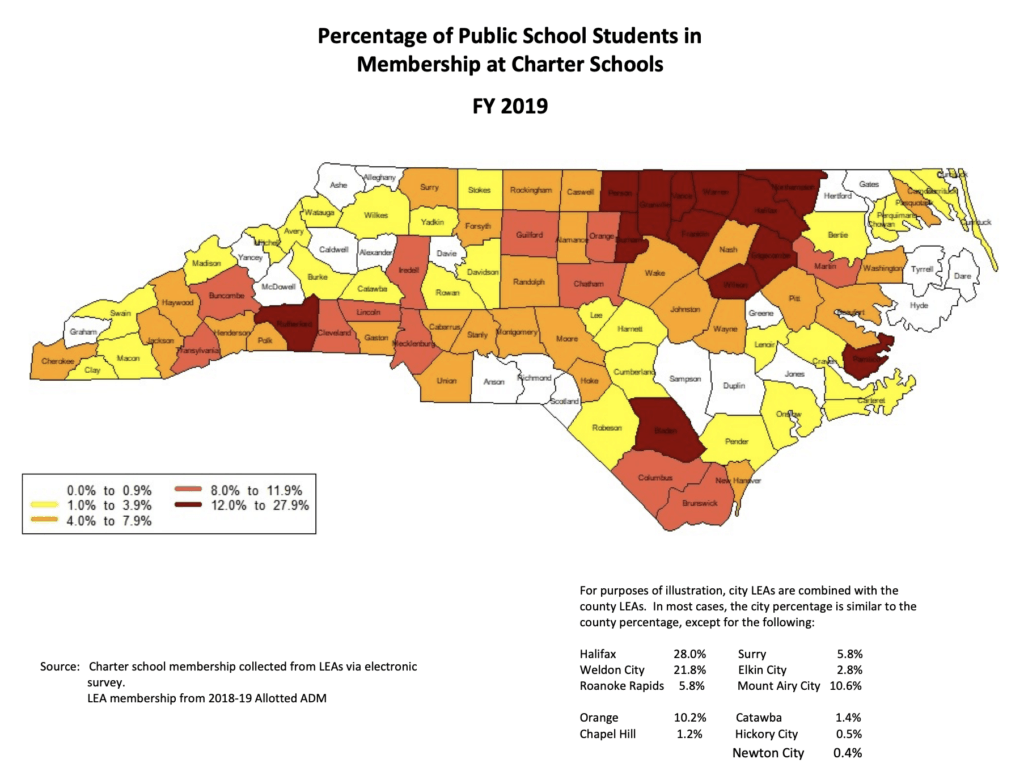

Jump to 2019, and there’s a lot less white.

While charter schools are still public schools, having more students in charter schools means that districts are receiving less money from the state, which can impact the money they end up spending locally if they don’t true up their budget to meet fiscal realities.

And the impact of charter schools also hits some poor areas the hardest, according to Lopes.

“Your poor districts have a lot of charters schools, and kids are going to those in a greater percentage than some of the other districts,” he said.

Another possible reason that fund balances have been falling was offered up by Price. School districts used to have more flexibility in how they used state teaching positions allotments. One of the things they did was leverage state funds to offset local expenditures, according to Price.

Here’s an example of what that might have looked like. The numbers used aren’t real – they’re just to make the illustration easy.

Once upon a time, the state used to give districts funds equal to the average teacher salary for a position allotment. Let’s say that’s $50,000. The districts might get that money, and then transfer it to something different – let’s say instructional supplies.

Now they have $50,000 in state money for instructional supplies. They use that money to offset $50,000 that they may have had to spend using local money. But they really do need a teacher. So they take that $50,000 in local money and use it to hire a beginning teacher at $35,000.

That leaves them with $15,000 leftover that they can put in their fund balance for a rainy day. This is one way that school districts could leverage state funds to increase their fund balance. There are many other ways it could have been done.

The law changed in 2013, however, and districts were no longer able to do this. You can find the law change in the appropriations act of 2013, section 8.14, subsection (5b).

Those are many of the reasons why fund balances are lower now. But regardless of the reasons, they are lower.

So, let’s look back at the fund balance data and talk about what this means for school districts.

Where we are now

Now that we’ve established what a fund balance is and how we got to where we are, let’s look at the position of school districts around the state. We mentioned some of this data higher up.

For fiscal year 2019, fund balances ranged from $53,231,903 at Wake County Public Schools to -$3,780,572 at Wayne County Public Schools with an average fund balance of $3,621,620 and a median fund balance of $1,842,552.

Fund balances were not available for Public Schools of Robeson County and Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools in 2019.

Of the 115 school districts in North Carolina, six had negative fund balances. Those include: Wayne County Public Schools, Thomasville City Schools, Lee County Schools, Graham County Schools, Clay County Schools, and Cherokee County Schools.

A negative available fund balance usually means that liabilities in the local current expense fund outweigh cash on hand. The total fund balance, however, includes assets other than cash. So even if the available fund balance is negative, the total fund balance could still be positive, according to the Local Government Commission. But a negative available fund balance means that a district doesn’t have that extra savings they can spend in the event of an emergency.

Ten districts had fund balances of more than $10 million. Those include: Wake County Public Schools, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, Cumberland County Schools, Cabarrus County Schools, New Hanover County Schools, Rockingham County Schools, Durham Public Schools, Brunswick County Schools, Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, and Guilford County Schools.

In 2019, fund balances as a percent of expenditures ranged from almost 100% at Rockingham County Schools to -16% at Thomasville City Schools. The six districts that had a negative available fund balance also had negative fund balance as a percent of expenditures in fiscal year 2019.

Twenty-eight of North Carolina’s 115 school districts had an available fund balance that was less than 8% of expenditures.

For fiscal year 2013, fund balances ranged from $80,360,910 at Wake County Public Schools to -$128,343 at Greene County Schools, which was the only district to have a negative fund balance that year.

The average fund balance was $5,897,097 with a median of $2,903,894.

Seventeen of the 115 districts had fund balances of more than $10 million.

In 2013, fund balances as a percent of expenditures ranged from 100% at Caswell County Schools to -3% at Greene County Schools, which was the only district to have a negative fund balance as a percent of expenditures.

Twelve of North Carolina’s 115 districts had an available fund balance that was less than 8% of expenditures in 2013.

What difference does it make?

So what? Available fund balances are lower than they once were. What impact does that have? It could be a lot, it turns out.

Lopes said one of the biggest uses of the fund balance is to keep schools afloat while the General Assembly works through a budget.

You see, the state budget usually isn’t finished being hashed out by lawmakers until June 30 at the earliest. And as we’ve seen from recent sessions, it can take much longer. Lopes said that schools can’t wait for the state budget to make decisions. They can’t wait until the summer to hire teachers for the fall. They can’t wait to make decisions about summer school or year-round schools. They have to act early. And that’s where their available fund balances come into play.

“We always say that the fund balance is called the great eraser,” he said. “It allows you to go ahead and make decisions knowing that if the state doesn’t fund you at the level you hope they do, you can continue to fund at the level you want and make corrections.”

Beyond that, Lopes said districts need fund balances for periods of economic hardship. It helps districts sustain themselves through tough times. And going to the county commissioners for help isn’t necessarily going to work when everybody’s hurting financially.

“It sounds good that you can go to the county commissioners … but they’re facing their own issues,” he said, adding later: “They’re not going to have a pot of gold that they can go to.”

And so, now that the state is embroiled in the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic downturn, the fact that school districts have lower fund balances than they once did is important.

“Until we know the answer as to who’s going to come in and provide the resources, that fund balance is going to have to be used to get them through this,” Lopes said.

Lawmakers returned earlier this month to take up the distribution of about $3.5 billion in federal funds meant to help the state address COVID-19. They spent about $1.6 billion. Of that, roughly $231.6 million went to K-12 education. Additionally, the federal government is sending about $396.3 million directly to school districts for COVID-19 relief. But these are immediate solutions, and it’s not clear that COVID-19 is a short-term problem.

Meanwhile, because of COVID-19, the state could be facing roughly a $4 billion shortfall. The state has a little over $3 billion saved up. For the first time in years, lawmakers are not dealing with a surplus and might have to make tough decisions.

“It’s going to depend on what the state’s going to do to help schools get through this,” Lopes said. “If they cut their funding, then obviously the fund balance is going to have to pick up that cut. And most school systems … aren’t going to have the fund balance to pick up that difference.”

In a press release today announcing the filing of multiple bills, Senate budget writers wrote that “every budget decision made will have as one consideration the absolute aversion to cutting education budgets and teacher salaries.”