When state law required every North Carolina school district to submit an annual Literacy Intervention Plan (LIP) by Oct. 1, the mandate was clear. What has been less clear until recently is what strong implementation actually looks like once the paperwork is submitted.

That question came into focus during a recent report to the North Carolina State Board of Education, where one district’s work was spotlighted as having moved well beyond compliance.

Rather than assuming understanding, Nash County Public Schools verifies it by intentionally moving the plan from a district expectation to classroom action. Each spring, district leaders review the effectiveness of current resources and structures, then begin developing the LIP for the following school year.

The plan is shared with principals through monthly recorded presentations and distributed in advance of leadership meetings. During those meetings, leaders pause to check for understanding, clarify expectations, and surface questions. School leaders then share the LIP with teachers, staff, and families and use it to develop an aligned school improvement plan (SIP) grounded in their own data.

The LIP functions as more than a compliance document. District and school leaders describe it as a tool for building a shared instructional language — one grounded in intentional scheduling, aligned instructional materials, collective responsibility, and continuous reflection designed to ensure every student receives high-quality reading instruction from the first day of school.

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Master schedules as an instructional lever

Nash County began its summer principal retreat with specific criteria for examining and refining master schedules through an intentional literacy lens. In addition to the recommended research-based instructional time focused on foundational skills and comprehension — 90 minutes for grades 3-5 and 120 minutes for K-2 — schools are required to include a protected 45-minute intervention block.

District leaders emphasized the importance of safeguarding instructional time, particularly for students with disabilities. District and school teams examined schedules to ensure students were receiving all three tiers of instruction without being pulled from core or targeted instructional support times.

But the work did not stop with scheduling. Once schools opened, district and school leaders conducted walkthroughs almost immediately to provide feedback and timely support, ensuring schedules translated into instructional practice. Interventions are embedded in the schedule and begin by September, using prior-year data and documentation until new data are collected.

Reducing variability through vetted instructional materials

Another cornerstone of Nash County’s approach is a streamlined, district-approved list of instructional resources for Tier 1 and Tier 2 instruction. This has become especially critical as the district welcomes a growing number of teachers entering through nontraditional licensure pathways.

For Tier 1, teachers use aligned, high-quality materials designed to ensure all students have access to grade-level curriculum and strong core instruction. These resources create a common foundation, reducing variability, and strengthening instructional coherence from classroom to classroom.

For Tier 2, educators implement additional, targeted supports for students who need more intensive intervention. These evidence-based tools and strategies are intentionally selected to align with core instruction, allowing interventions to accelerate learning without disconnecting students from the grade-level standards.

By streamlining resources across tiers, Nash County minimizes fragmentation, strengthens instructional clarity, and ensures that every support, whether core or supplemental, works together to move students forward.

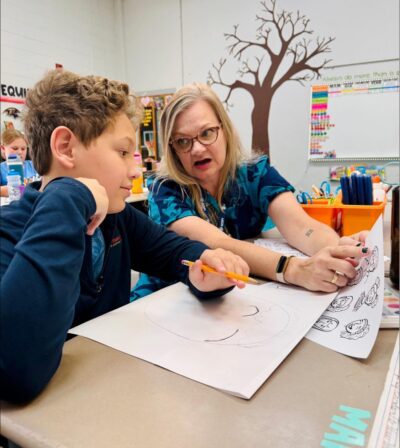

By vetting materials at the district level, Nash County ensures classrooms use resources grounded in research, built around complex text, and designed to be explicit and systematic. Teachers receive these materials from day one. Over time, the impact has become increasingly evident. First- and second-year teachers demonstrate a strong command of core resources and how they connect to the professional learning they receive through Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS).

“For many new teachers, fully understanding the science of reading is a multiyear process,” said Monique Hargrove-Jones, the district’s executive director of elementary education and early learners. “But if the materials are strong, explicit, and well-designed, teachers can deliver effective instruction even as their understanding continues to deepen.”

District and school leaders describe “aha moments” emerging as teachers begin to understand not just how instructional routines work, but also why. Teacher assistants and tutors are also trained in these instructional resources, ensuring consistent, high-fidelity instruction across all settings.

Bringing parents into the literacy process

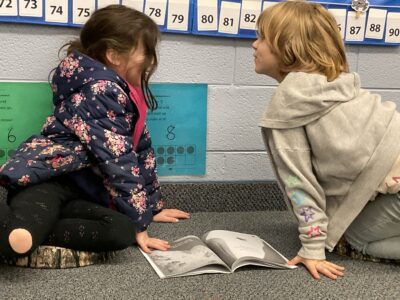

Kristen Tedford, principal at Benvenue Elementary, shared that parent engagement has also become an intentional part of the school’s literacy framework. Through initiatives like Parent University, families learn about intervention strategies aligned to their child’s specific needs.

Using assessment data, staff teach parents targeted strategies connected to foundational skills such as phoneme segmentation. Families are also introduced to the academic language commonly used in literacy conversations, helping them feel more confident supporting reading at home.

Suzanne Weaver, Benvenue’s Master Classroom Leader (MCL), shared how a recently developed parent resource is already strengthening partnerships between home and school. The resource, Reading Road Map for Families, explains key literacy terms and assessments in clear, accessible language. During conferences, teachers use the guide to identify specific areas where a child needs support and to share aligned, research-based strategies families can practice at home.

Monitoring implementation and being willing to pivot

School leaders across Nash County clearly understand their role as instructional leaders and active participants in continuous improvement. Examples of districtwide practices for school principals include:

- Reviewing weekly lesson plans with nonnegotiable instructional components,

- Conducting daily walk-throughs focused on fidelity of implementation,

- Regular progress-monitoring data reviews,

- Participating in weekly professional learning community (PLC) discussions, and

- Establishing extended PLC blocks for deeper data analysis and embedded professional development.

Data conversations have also shifted from compliance to responsiveness. While interventions are typically implemented for six to nine weeks, teams are prepared to pivot sooner when data indicate a need.

In some cases, data revealed that certain teachers were particularly effective at teaching specific skills. Rather than framing this variation as a deficit, district leaders began examining Susan Hall’s walk-to-intervention model, which allows students to receive short-term, targeted instruction from a teacher with demonstrated expertise in a given skill area. This approach reflects a shift toward collective responsibility, grounded in trust, shared professional learning, and continuous improvement.

Building coherence through shared leadership

District structures have further strengthened coherence.

Monthly meetings bring principals, MCLs, and district instructional specialists together around shared priorities. Time is intentionally built in for joint learning, followed by planning time for school teams to apply new tools immediately with district support.

Following each major benchmark assessment, the district also convenes face-to-face, grade-level PLCs across schools. These sessions allow teachers to analyze data, share practices, and plan next steps — critical for maintaining alignment and reducing instructional variability.

What the data shows

Nash County Public Schools’ disciplined approach is producing measurable results. The district has reduced the percentage of K-3 students at risk for reading difficulty at a rate comparable to, and in some cases faster than, the state average.

Growth on DIBELS benchmarks mirrors statewide trends, while end-of-grade reading results show even stronger gains. Since the passage of the 2021 Excellent Public Schools Act, the district has seen:

- A 9-percentage point increase in Grade 3 reading proficiency (state average: 2)

- A 21-point increase in Grade 4 (state average: 13)

- A 24-point increase in Grade 5 (state average: 11)

- Exit from low-performing status in 2022-23, with three consecutive years outside that designation.

These gains were not accidental. They reflect a sustained commitment to collective accountability, intentional implementation, and clear communication.

Nash County’s experience offers a clear message: Literacy Intervention Plans matter most when they stop merely being plans and start reshaping practice.

Recommended reading