While it feels longer to many, this Saturday, April 3, marks three weeks since Gov. Roy Cooper first announced the closure of all K-12 public schools in North Carolina.

“The panic set in,” said Mattamuskeet Elementary School special education teacher Callie Luker, describing her initial reaction to Cooper’s school closure announcement. “Internet is not something that all my kids, my students especially, have access to,” she added.

However, within hours, Luker had a plan in place.

“If we’re going to be home for an extended time, I need to think of something that really engages them,” Luker said as she described her thought process that Saturday afternoon. She knew her students needed hands-on learning experiences and loved working in their school garden, so she picked up the phone and called several gardening seed companies.

“I told them that we’re looking to go to virtual learning and a lot of my students are unable to read, a lot of their family members struggle with reading, so I’m really looking for something hands-on,” she said as she asked them to donate seeds and plants. “The response was amazing.”

Soon after, Luker sent seed kits home to her students using the buses delivering school meals. Each kit contained seeds, dirt, a pot, and a popsicle stick to mark their plantings. Luker recorded a YouTube video of herself opening one of the kits, describing the contents to her students, and asking them to do the same.

“To see my student who doesn’t have a lot of words do an un-boxing video, that was the most I’ve ever heard him try to explain what he was thinking ever, and I’ve had him for four years,” she said. “We’re having fun and we’re still learning, and my kids are still engaged and that’s what matters the most.”

‘School without walls’

Across the state, educators, students, and parents are adjusting to a new normal. The Friday before Cooper announced statewide school closures, Hyde County Schools (HCS) Superintendent Steve Basnight told his principals they should spend the next week working with students on their various digital tools in case they ended up needing to close.

“I met with my staff, and they were all in disbelief,” Mattamuskeet Elementary School Principal Allison Etheridge said. Ocracoke School Principal Leslie Cole told her teachers to take the weekend to think about what school would look like for them if they had to close.

The next morning, Etheridge went to school and created a Google form to assess her students’ digital accessibility. That afternoon, the governor announced all schools would be closed for two weeks.

Hyde County Schools

— 3 schools

— 62 teachers (2017-18)

— 584 students (2017-18)

— 2017-18 Student demographics: 2% Two or more races, 21% African American, 21% Hispanic, 56% Caucasian

In Hyde County, teachers took that Monday through Wednesday as workdays to prepare for virtual learning, and “school without walls” resumed that Thursday, March 19.

“One of the things we’ve told our staff is we’ve done away with walls and we’ve done away with time, because in a virtual learning environment, there is no time,” Basnight explained. “It’s not about the 8:00 to 3:00 school day. You have to take the virtual environment and put it into your classroom.”

“We’re still in school,” fifth grade teacher Kristy Marslender said. “It’s just our walls have expanded. Our walls are now the Hyde County borders. Learning is taking place everywhere.”

Getting students and teachers online

The first order of business for Hyde County educators was to assess students’ access to internet at home. The district is one-to-one with every student having access to a Chromebook which they were able to take home.

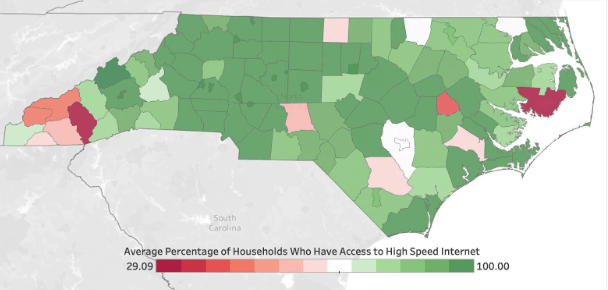

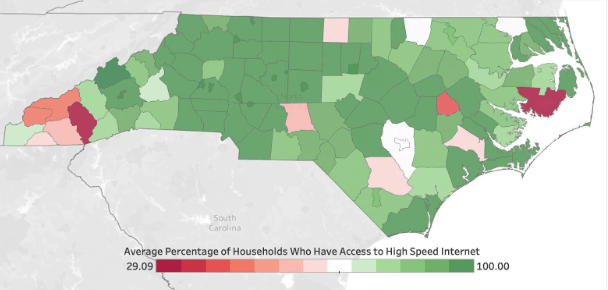

On any map looking at internet access, Hyde County sticks out. The map below, created by the state Department of Public Instruction digital teaching and learning division, shows the average percentage of households who have access to high speed internet. Hyde County is the dark red county on the eastern edge of the state.

The district acted quickly to assess student needs and distribute Wi-Fi hot spots to those who needed them. Several of these hot spots were ones Verizon had donated during Hurricane Dorian relief efforts. The district was also able to write a grant for more hot spots through their community foundation.

As the schools got hot spots to their students who needed them, teachers worked with students and parents to set them up and make sure they could connect. Before the statewide stay-at-home order was in effect, Luker traveled to one of her student’s houses to show her how to connect to the internet using a hot spot.

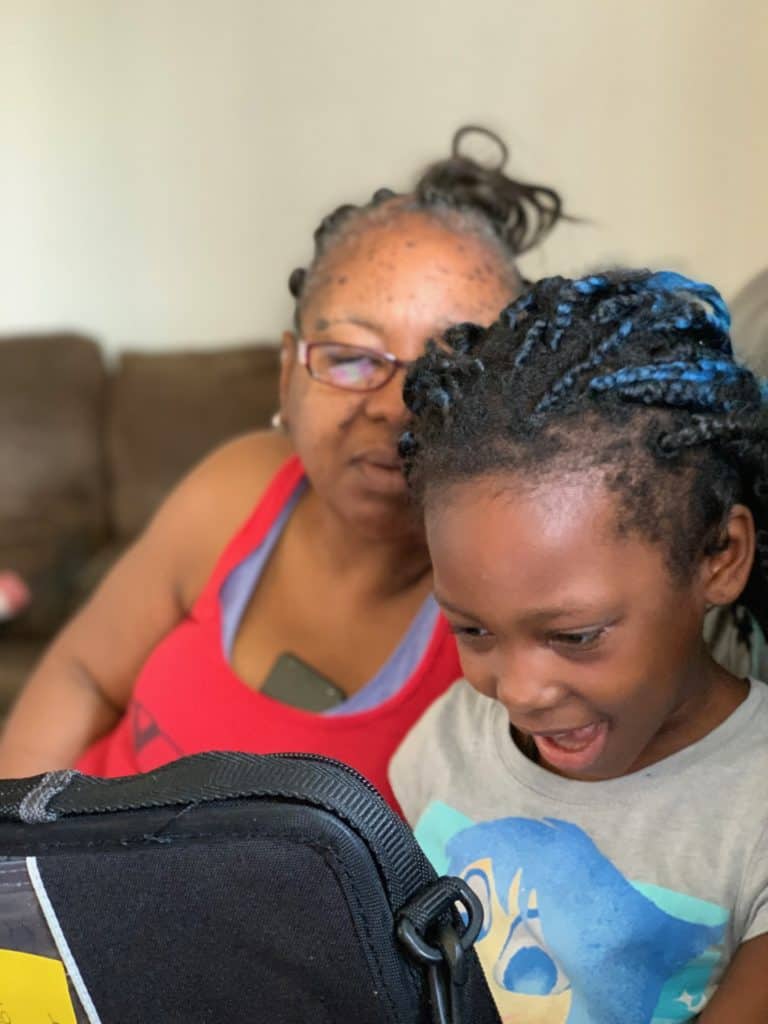

“Seeing her being able to get on the internet for the first time was a day I’ll never forget,” Luker said. “They didn’t have internet access. … She called her grandmother over and showed her that she could do it — her grandmother just couldn’t believe it.”

In addition to students without access to internet, several educators in the district also have connectivity challenges.

“It’s one thing to say our students don’t have internet access, but we have teachers who don’t have internet access,” Basnight said. “Getting assignments out to our students becomes a challenge when our teachers don’t have internet access.”

Etheridge doesn’t have Wi-Fi at her house, so she has been using a hot spot on her phone to connect. However, her kids also need to use it to do their assignments, which has created problems.

“If I’m working from home, anytime my phone rings [my kids are] dropped out of anything they’re doing,” Etheridge explained. “If I have a busy afternoon and the superintendent wants to have a Zoom meeting, that’s great, but that means that’s three hours where there’s no way my kids can do their work.”

Teachers and administrators who are struggling with internet access at home can come to school, but the district has limited the times they can be there and the number of people who can be there to maintain social distancing.

‘This is our third first day of school’

While educators and students on Ocracoke Island are used to missing a few days of school a year due to high winds, hurricanes, and other weather events, this year was different. Hurricane Dorian ripped through the island on September 6, leaving devastation in its wake. Ocracoke School, the only school on the island, was completely flooded.

“We were out 22 and a half days in the fall,” Ocracoke School Principal Leslie Cole said. “This is our third first day of school. We had August 28, and then we had October 7. And then we had March 19, our first day of virtual. I’m really hoping that’s it.”

Because the entire first floor of Ocracoke School flooded during Dorian, the school had to split up into three locations when they came back in October. Grades 2-5 stayed in the original school building in the only four classrooms located on the second story. Grades 6-12 located in the North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching (NCCAT) building on the island, and pre-K through first grade located in a daycare center that was not being used. The three locations staggered their start and dismissal times so parents could drop their kids off at multiple locations. Art, physical education, and other teachers who serve all grade levels had to travel between the three locations every day.

In addition to the physical disruption, many students and teachers lost their homes and possessions during the storm. “I think the number we had was 40% of our kids and 60% of our teachers displaced originally,” Cole said.

Despite these challenges, students and teachers had adapted and were trying to make up for lost time when the pandemic hit.

“We were in a little bit of a groove,” Cole said. “The kinks had been worked out, and then this.”

While none of the teachers would have wished their experience with Dorian on anyone, they did feel like it prepared them and their students for the disruption caused by the pandemic.

“When this happened, it’s sad to say they are kind of used to it because they’ve been through so much in the last year,” said Alice Burruss, the first grade teacher at Ocracoke School. “With all the loss I had personally and all the loss we had at school, I found strength in myself and the kids found strength in themselves that they didn’t know they had.”

Cole agreed. “I found in some ways we were ahead of the game in terms of being flexible and open to new things because we had to back during the storm,” she said.

With no confirmed COVID-19 cases in the county as of Thursday, April 2, Owens said that while the students are certainly experiencing the disruption of learning at home, it is a different sense of loss than they felt after Dorian.

“While this is going to be a second memorable event for them on Ocracoke this year, the first, Dorian, taught them I think to appreciate what we have. So many lost so much — possessions, their home, their favorite bike. That sense of loss was so overwhelming then, that now it’s like an inconvenience that we’re home, but it’s not the same type of feeling of sadness.”

‘Everyone is like a first-year teacher’

As her teachers drew up their plans to shift online, Cole urged them to give up the idea that they can do this perfectly and move their existing classrooms online in the same format.

“Everyone is like a first-year teacher in this situation,” said Cole. “You’re going to crash and burn, you just are, and that’s okay.”

Etheridge echoed those sentiments. “We fell into the trap of everybody trying to have the same assignments they were having during school,” she said, “and the problem with that is you don’t have the actual teacher at home.”

Etheridge also emphasized to her teachers that they need to be aware of how much work they are assigning, especially because some of it may require parental help and many parents are still working or have multiple children they’re trying to help.

“The quality is more important than the quantity,” Etheridge said. “It’s not the amount of work. It’s something that will engage the students and keep them moving forward and learning whatever it is.”

Over the past two weeks, teachers have adapted their lessons in response to student and parent feedback. The typical day looks different across grade levels, but all teachers hold office hours when students and parents can get individual support.

Burruss starts each day with a Zoom morning meeting with her class. “We go over the lesson. We talk about our highs and lows for the day,” she said. “I stay on Zoom for a few hours and they can go in and out if they have questions.”

Fifth grade teacher Jeanie Owens also starts each day with a morning meeting on Zoom. “For the social emotional aspect, I needed that moment with them where we could all meet.”

For many of the educators I spoke with, the hardest part of the past few weeks has been not seeing their students in person.

“I really feel that the best part about anyone’s day in education is being with the kids, and that’s gone,” said Cole. “None of us went into this to teach to a computer. That’s the saddest part of it all — missing the kids, and them missing their friends, and all that makes a school a school.”

Burruss echoed Cole: “The biggest challenge is not being with the students every day. By with them I mean not being able to see their expressions and know how their day is going and being able to really take what we’ve taught them and see how they’re incorporating it into other parts of their learning and their lives. It’s really difficult not to see them every day.”

What’s next?

On March 23, Gov. Cooper extended school closures until May 15. A handful of states, including Virginia, have canceled school for the rest of the school year.

Hyde County educators are not sure what the future holds, but they agree this experience will change all of them.

“I think we’re going to be better for it, but with that goes with a lot of growing pains,” said Cole.

“Our teachers are now also students. Whether they like it or not, they’re having to do it,” Etheridge said. “I think we’re going to see a boost in our technology usage from here on.”

Fifth grade teacher Kristy Marslender said this experience has forced her and her fellow educators to “open the door to learn new things.” She already knows one way her teaching will change next year: “If I have a substitute next year, it’ll be no problem to just have a video ready to teach the lesson rather than leaving a worksheet,” she said.

For now, Hyde County educators will continue following their motto — “Do what’s best for students” — whatever that may look like. Every teacher and principal I spoke with expressed their immense pride in their colleagues, students, parents, and community for the resilience they’ve shown and the support they’ve given each other.

“I really thought there would be some sort of resistance to wanting to learn this way from both the parents and the students,” Burruss said. “In a time like this, after all the things we have been through on Ocracoke, this could have been ‘I give up’ and ‘I can’t take much more.’ I see that everybody’s been really resilient.”

Owens added, “The Ocracoke faculty has been incredibly resilient this year. To watch a group of professionals who have lost their own personal belongings and who have experienced a tragedy overcome that and then be asked to again change things up, they have done it with dignity. They have done it with enthusiasm.”

Correction: A previous edition of this post incorrectly stated Callie Luker teaches at Ocracoke School. She teaches at Mattamuskeet Elementary School.