Leslie Cole, principal of Ocracoke School, saw Hurricane Dorian make impact and ravage Ocracoke Island. She watched as the storm tore through her campus, the back end of the hurricane’s eye striking during high tide and causing massive flooding.

She called her superintendent, Stephen Basnight.

“It’s bad,” she told him, and urged him to prepare himself.

“I got out there,” he said, “and I still wasn’t prepared.”

The entire school flooded, and wind and flying debris damaged exterior walls and structures. Island-wide, a sense of loss was pervasive. The county’s emergency management said 70% of homes and businesses were flooded or damaged, rendering them uninhabitable. Basnight said there were only four places on the entire island that weren’t impacted.

“Nothing’s not affected,” he said. “You can’t imagine how bad it looked. It was absolutely terrible.”

Still, with morning light, recovery efforts began. Basnight said the community is strong, unified, and already focused on rebuilding.

“These are special people,” he said. “The next morning — I mean the very next morning — they started cleanup.”

Hyde County has three public schools. Two, Mattamuskeet Early College High School and Mattamuskeet Elementary, are on the mainland of North Carolina in Swan Quarter. They suffered roof and exterior damage, as well as some water infiltration. But on the mainland, it’s easier to start the process of mitigation and repairs.

The district was able to open these schools and resume classes on Tuesday.

Progress, however, will not come so quickly for Ocracoke School. Situated on an island, the dynamics of recovery are a bit more strained.

With Ocracoke Island evacuated, the recovery effort lacked full power until residents returned on Monday and Tuesday. And while island residents are helping, many must tend to their own properties.

“Most of our students and staff on the island are homeless, technically,” said Julio Morales, the school district’s public information officer. “So there’s a lot that we have to deal with.”

Help for schools following storms often comes from contractors who muck, gut, mitigate, and repair. But that process can’t start without adjusters and investigators making visits first. Restricted access and curtailed ferry trips to the island have slowed the process of getting visitors to the school.

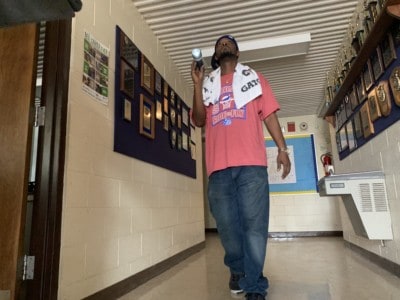

Basnight, as part of the county’s recovery team, has authority to issue ferry permits to these individuals, but the parade of inspectors and adjusters are only beginning this week. Basnight is on the island, and will remain there at least through the week, helping with cleanup and assessment.

Basnight said that returning kids to a greater sense of normalcy is a priority, but that normalcy in schools will be a long-term goal. The district does not yet have a timetable for getting the school back up and running. They are weighing several options for alternate classrooms to resume teaching, but each of these come with some disadvantages.

In other school districts hit by storms, school leaders develop plans for moving students from damaged schools to the county’s school-ready campuses.

“But we’re separated by water,” Morales said.

Added Basnight: “That’s the next level of complication. Everything’s got to come by boat. Nothing is close.”

That includes the open schools in the district. For Ocracoke School students, it would mean a ferry ride.

Officials have considered a plan where students would travel by boat to one of the county’s mainland campuses, attending school for extended days two or three times a week. Teachers would start holding classes on the ferry ride and students would join classrooms in Swan Quarter from 10 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. before riding the ferry back home.

“It’s long days, though,” Morales said, “And not ideal.”

Another option, suggested by FEMA, is asking Gov. Roy Cooper to approve 25 modular units for the island where the county can hold classes. However, there is only one site on Ocracoke large enough to house so many trailers — the ferry parking lot — and it is currently playing host to hundreds of flood-damaged cars.

These cars will be moved after insurance adjusters make it to the island for claims investigation, but as soon as the lot clears, emergency management plans to use the lot to set up a health center.

“That gives you some perspective on the scope of this and everything that’s involved,” Basnight said.

The top option thus far is holding classes on the island in borrowed space. The county and local businesses have offered help, but with nearly every structure on Ocracoke Island impacted in some way, finding a single location proved unfruitful.

“When everywhere is affected, there’s no place where you can put all of the kids in one place,” Basnight said.

The district has identified six different sites — like daycare facilities and community centers — where classes can be held while the school is repaired. This would mean dividing students across the island. It’s also not an ideal solution, but given the challenges, it may be the quickest way to get classes restarted.

“It’s really unbelievable what they’re dealing with,” Basnight said of island residents. “My goal is to give the kids some piece of normalcy, getting them back to school and back to a place with people they feel comfortable with.”

For now, residents are helping however they can. Some have found facilities and volunteered to host elementary students for 4-hour stints, where the children talk, play, watch movies, and engage in crafts or other activities. It’s not sponsored by the school, but Morales said it is a major help in allowing adults to focus on home restoration and providing children an opportunity to socialize and process their experiences.

“That’s one thing that I’ve been so surprised about with the Ocracoke community — they are so united,” Morales said. “Whatever happens, they get together and make it happen. This one was a really low blow. But everyone is working together and will recover from it.”

Morales and Basnight said they’ve also been touched by the support beyond the Hyde County community. He said the district has been contacted by people as far away as California, and by many in South Carolina, Virginia, and throughout North Carolina. Whether they were born on the island, have family there, or hold fond memories from vacations — they feel a connection to the island and want to help.

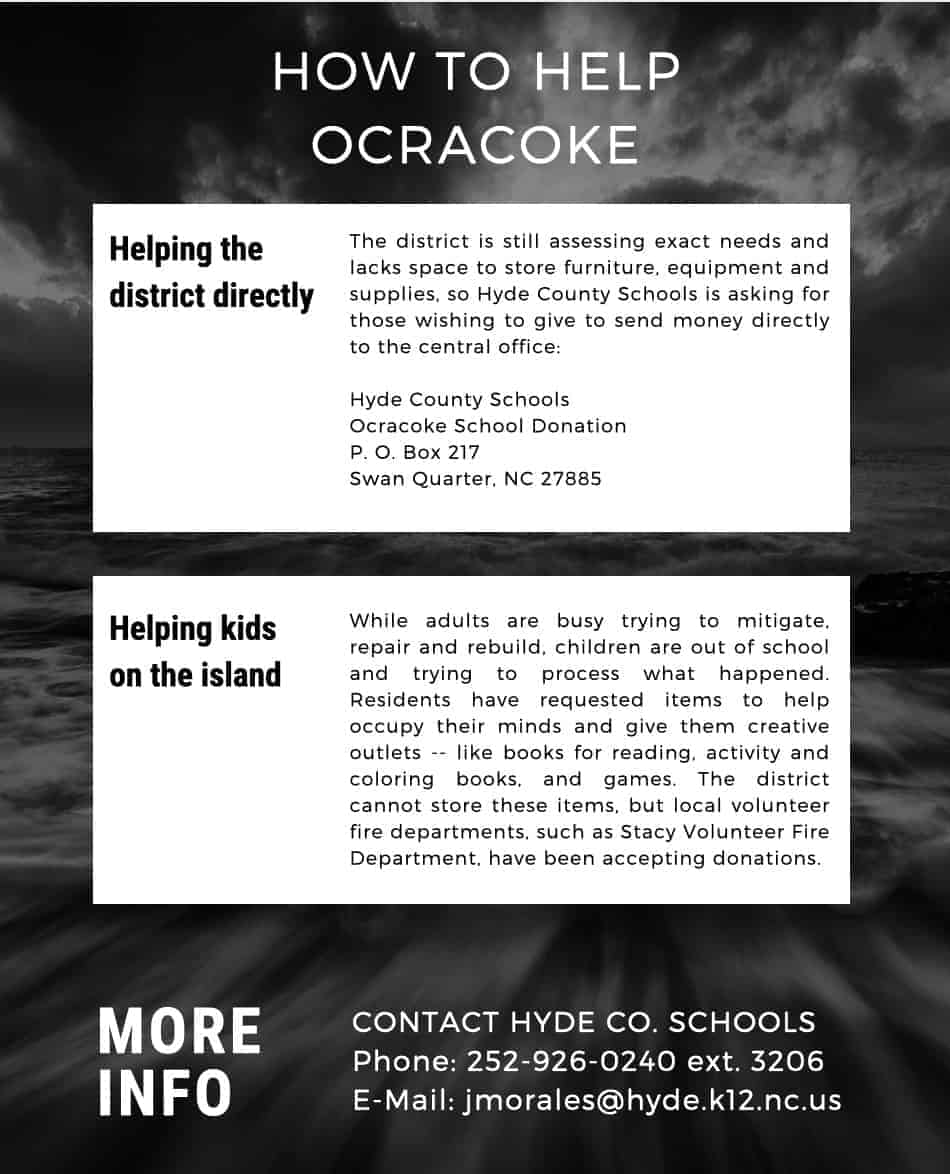

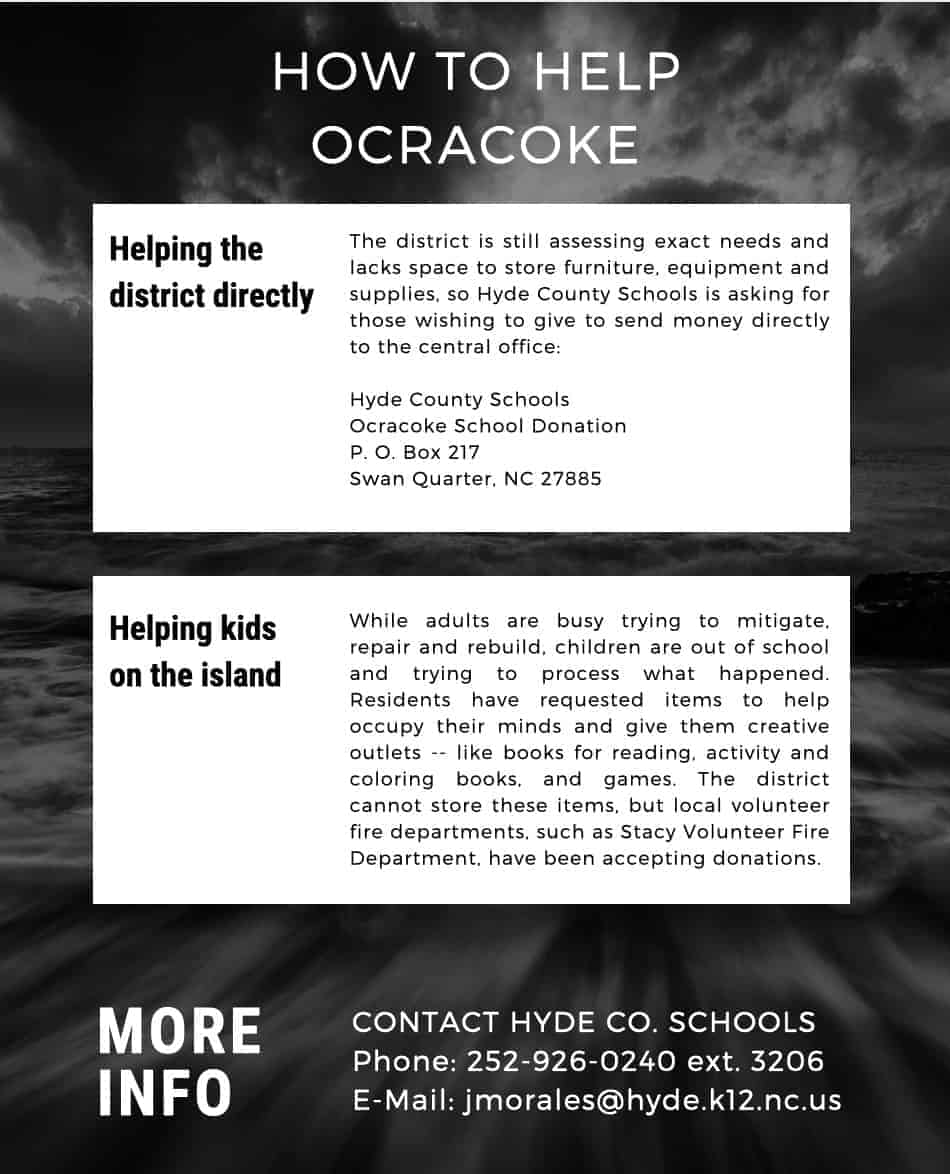

“It’s been very humbling, but also overwhelming,” Morales said. “With the school flooded and not cleaned out yet, we don’t even have space to hold items. So we’ve been asking anyone who wants to help to send money donations to the central office, and once we’ve cleared the school and we have a better idea of the furniture and supplies we need, we’ll post that information.”