Former Gov. Bev Perdue said that its incumbent on the federal government to fund internet infrastructure in its upcoming COVID-19 stimulus bill.

She said that during the last recession in 2009, North Carolina worked with the federal government to get stimulus money to expand the state’s internet infrastructure and connectivity. In the wake of a school year that was nearly half online, she said it’s clear the federal government needs to do that again.

“We need to figure out a way to finance a massive infusion of infrastructure into our cities and small towns,” she said.

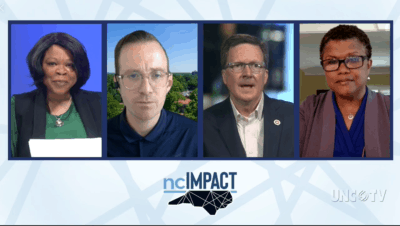

Perdue was part of a Q&A about the digital divide on July 30. Joining her were Sen. Deanna Ballard, R-Watauga, a chair of the Senate education and education appropriations committees, and Sharon Contreras, superintendent of Guilford County Schools.

Perdue said that North Carolina was well positioned to weather the switch online when in-person classes were moved online back in March due to COVID-19. But it also became clear that more work needed to be done, she said.

“The digital divide — that terrible known fact of the haves and the have-nots in North Carolina — became much larger than any of us thought,” she said.

Perdue said around 600,000 students in the state did not have a device at home or connectivity. So while prior efforts made sure that schools themselves could access the internet, some students were at a loss when they couldn’t go to the classroom.

“The kid can learn and use the internet when the kid is in school, but when he or she goes home, there is no connectivity,” Perdue said.

She called on state leaders to talk with North Carolina’s congressional representatives and urge them to support money in the federal stimulus bill to be used on enhancing internet infrastructure and connectivity in North Carolina.

Ballard agreed that the federal government would need to step in, particularly with North Carolina facing a shortfall going forward. She said, however, that infrastructure alone wouldn’t be enough. She said that service providers need to be encouraged to go in and bring services to areas where there are none.

Ballard also highlighted the work that the General Assembly has done in spending federal stimulus money to increase broadband connectivity after COVID-19 and creating and expanding the Growing Rural Economies with Access to Technology (GREAT) Grant Program.

This program grants money to increase broadband infrastructure to the most “economically distressed counties.”

Contreras called on the state General Assembly and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to do more for North Carolina connectivity.

She said lawmakers should try to negotiate with telecom companies to provide more technology and connectivity in North Carolina. She said the FCC should “wield its influence” over telecoms to do the same, and should distribute the billions of dollars it has the authority to send to libraries and schools.

Contreras said that while it was impossible to know with certainty, it looked like about 17% to 18% of families in Guilford County don’t have access to high-speed internet. And the racial gap is even worse, with 26% of Latino families and 20% of Black families without the number of devices needed at home to support online learning for their children.

Exacerbating the move online is the fact that prior to the pandemic, the percent of free- and reduced-price lunch students in Guilford County was around 67%. In addition, they have about 3,000 homeless students.

She said that about 2,300 students never logged on for online learning and 4,200 only logged on in the first couple of weeks. Thousands more only got on sometimes.

“Clearly the United States education system was not built to deal with extended shutdowns,” Contreras said.

When schools shut down in March, the county distributed devices to students and set up hot spots, relying on philanthropic money to cover some of the expenses.

But she said: “Philanthropy is an inadequate solution to systemic racial inequities.”

Watch the Q&A below.