This year, Durham-based MDC chose nine organizations to join a program called “Learning for Equity: A Network of Solutions” — or LENS-NC. The program aims to improve outcomes for students at the intersection of race, income, and learning differences. This article is part of a series introducing our readers to these nine organizations.

Disability Rights North Carolina (DRNC) has had other names in its long history, but one of its missions has stayed constant – drawn from its roots in 1970s coalitions that fought for sweeping reform in the education of special needs students.

Once a state-controlled agency, DRNC is an independent organization that tailors its advocacy to changing policies and emerging issues – as seen now with its attention to COVID-19 impact.

But one thing remains the same: the organization’s focus on systemic impact, including to make special education more accessible.

“Our mission, I see it very broadly, is to significantly improve educational outcomes for all students with disabilities in the state,” supervising attorney Virginia Fogg said about DRNC’s education team, which she leads.

“And maybe I would say educational outcomes and school experiences. Because there’s a lot of heartbreaking things about our work, but some of what’s hardest to see and process is how school is just not a good fit for our clients.

“And if you think about it, if you’ve ever been in a situation where you didn’t fit in, and you were required to spend six and a half hours a day, five days a week, 185 days a year in that environment, what effect would that have on you? On how you feel about yourself?” she said.

A brief history of DRNC

Thirteen years ago, on Halloween, the DRNC name was born. But the federally-established organization for protecting and advocating for disabled people was born much earlier.

After a news report in New York in 1972 revealed abuse, neglect, and lack of services at a state institution for people with disabilities, Congress mandated the creation of protection and advocacy organizations in each state.

In North Carolina, that organization was the Governor’s Advocacy Council for Persons with Disabilities (GACPD) – a state agency. It worked with other state agencies to improve the lives of people with disabilities. Changing a system it was part of, though, proved difficult.

Iris Peoples Green, a supervising attorney on DRNC’s emergency management and disaster relief team, joined when the organization was still called GACPD.

“I think they realized that some of the changes that needed to happen, couldn’t happen while we were in state government,” Green said. “We worked with people in state government, I guess the organizations that kind of help try to support people with disabilities. But it wasn’t effective.

“We had to get out of state government, as it was some of our state agencies that were the ones we might need to sue.”

Carolina Legal Assistance (CLA) was a nonprofit that had been fighting for disability rights since the 1970s. When the state split GACPD out of state government, Gov. Mike Easley appointed CLA – which changed its name to Disability Rights North Carolina – as the state’s protection and advocacy agent.

Building a mission of systemic change

CLA was an obvious choice, Green said. Along with other grassroots organizations, CLA had brought statewide lawsuits to fight for systemic change in treatment of people with disabilities.

One of those cases, the Willie M case, included remedies to ensure that adolescents with disabilities received education services.

Willie M involved four kids whom the courts labeled “juvenile delinquents.” The court found they had demonstrable mental health problems. As one journal article on the case put it:

“The mental health and education systems had routinely rejected these and other similarly situated children, expelling them from school and calling them psychiatrically untreatable. Funds were not available to provide adequate placement and treatment, even if such treatment could be discovered. There was nowhere for these children to go except to prison, euphemistically known as reform school or training school, or an adult ward of a psychiatric hospital.”

From “Willie M: A Legacy of Legal, Social and Policy Change on Behalf of Children”

The four named plaintiffs represented a class of children in similar situations. The state initially estimated the class might be 50 kids, but after it reached a settlement and opened the class, membership grew to 1,650 by 1999.

The settlement required such things as individualized treatment plans, treatment that was child-based rather than program-based, “wrap-around care” for children with multiple issues, treatment in the least restrictive alternative setting, a continuum of care, paid paraprofessional mentoring, and therapeutic group homes.

When Green joined GACPD, she was part of the team monitoring execution of the settlement. To this day, she takes time every year to look up names of the kids who benefited under the program to make sure they are OK – or, more specifically, to make sure they’re not in trouble with the system.

“That kind of scale, as big as that program was and how it benefitted those [children], that’s very satisfying to be a part of something like that,” Green said.

DRNC’s education team still pursues that sort of systemic impact, as it grows in personnel and reach.

Growth in recent years

Fogg is the supervising attorney who heads DRNC’s education team. When she joined DRNC in 2014, she was the only full-time person on the education team, with three part-time attorneys and advocates.

Six years later, the team is now five full-time attorneys and can tackle broader issues – such as impacts of COVID-19 and racial and economic disparities in special education outcomes.

About 40% of the more than 4,000 calls to DRNC annually are related to education, Fogg said.

Since before Fogg started, DRNC focused on getting students back in school from long-term suspension. That focus grew to include homebound and modified day schedules, because of policies evolved at the state level.

“And also working with kids that, although they are in school for an entire day, they’re still being excluded, in a sense, because they’re not receiving appropriate instruction,” added Reighlah Collins, an attorney on the education team. “And so they’re not actually able to access their education, even though they spend all day in a school building.”

Getting kids back into school has taken on a new meaning during COVID-19.

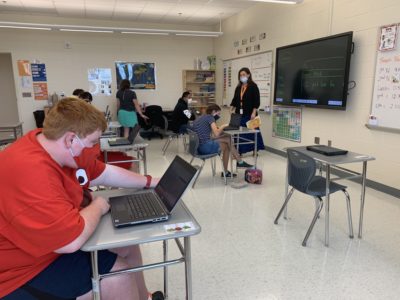

“It’s a particular challenge because a lot of our clients have a hard time accessing remote instruction,” Collins said. “Some of these kids can’t even sit still for longer than two minutes at a time. So getting them to be on a computer is nearly impossible.”

Much of the team’s cases recently, she said, involve children for whom “it’s unclear how they’re going to receive an appropriate instruction right now, with remote instruction being the norm.”

DRNC has negotiated in-person instruction for some of these students, and is getting paper materials and supports for others.

Continued focus on systemic impact

DRNC largely represents individuals. In doing so, however, the team pushes for remedies that will have broad impact.

“We try to take cases that are going to be able to have the systemic impact, and that varies, what that looks like,” Collins said.

“Sometimes, that is the state creating statewide guidance. Sometimes it’s the district changing their policy on homebound instruction or modified day. And sometimes it’s just getting school personnel trained, which we’d like to hope has a systemic impact.”

One of those strategies includes filing state complaints and pushing for district-wide training.

Any individual can file a state complaint and trigger a review by the Department of Public Instruction. If the state finds violations, it issues corrective actions. This has broader impact than advocacy in Individualized Education Plan meetings or pursuing a due-process hearing for a particular client.

“Right now we’re using a hybrid,” Fogg said, saying her attorneys continue to represent students in IEP meetings, advise some families on filing their own state complaints, and filing state complaints on behalf of others.

As part of the state complaint strategy, DRNC asks for training of entire school districts on whatever issues where the state Department of Public Instruction might find a school system deficient.

“I mean, if it happens to one child, basically, there’s no reason to think it’s not happening to a whole bunch of other students,” Fogg said.

Increased attention on marginalized students

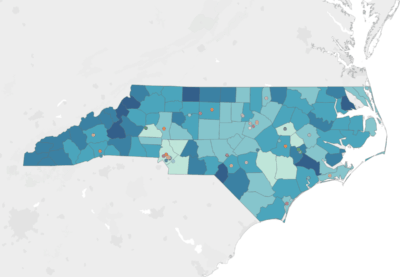

As part of the LENS-NC cohort, DRNC is also looking at the intersection of marginalized communities, education and disability rights — especially when looking at racial disparities.

“That’s a big focus of our systemic individualistic work,” Fogg said. “Black males are much more likely to be suspended, with or without disability. Even black females, and then, you know, Latinx males and females.”

As part of its LENS-NC project, which Collins facilitates, DRNC is looking at the misidentification and under-identification of Black and brown students with learning differences. It’s studying the issue at the state level and looking to other states for comparison.

“I think if you try to help those people, those people with disabilities that live in marginalized areas and try to make it OK for them, I think people will see that it will be OK for everybody,” Green said. “Everybody will be able to learn and live.”