About this parent’s guide: The term “learning differences” covers a wide range of challenges students may face in school, at home, and in their community. It includes all children who are struggling in school because their brains are wired uniquely — whether a learning disability has been formally identified or not. This parent’s guide can be helpful for all parents of students with learning differences. However, it is designed to be particularly helpful for those with children who have, or might have, a specific learning difference or other health impairment (e.g., attention issue) as defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

This is Part 4 of a series of parent’s guides related to learning differences. Click here to read Part 1, here to read Part 2, and here to read Part 3.

In Part 2 of this series of parent’s guides on learning differences, we took a step-by-step look at the Individualized Education Program (IEP) plan process. But what happens if IEP goals are not met and, through IEP monitoring, you see that your child either remains behind grade level or, worse, is regressing?

You could consider a private school that is either solely dedicated to instructing students with learning differences or integrates dedicated learning differences programs within their instruction model. These schools may be a temporary intervention where exceptional children get the dedicated resources they need and return to traditional public schools after progressing to grade level, or they may be a new home for kids who prefer the smaller environment and the comfort of being around other students like themselves.

“Under IDEA, the school actually has an obligation to consider private school placement as part of an IEP team decision,” said Virginia Fogg, attorney at Disability Rights North Carolina. “There’s a continuum of services under IDEA, and special schools are on that list. They’re considered pretty restrictive, but they are on the list. And it’s really, really, really rare in North Carolina to see an IEP team look at that as a possibility and to make that placement.

“I’ve never actually had a case when that happened. I do know of other cases where it happened, and unfortunately, usually, it’s where the child has significant behavior issues, and the school really just wanted the child out of the building.”

In North Carolina, there is a specific process that must be followed to get private school as a funded option through an IEP (Page 23 of the Exceptional Children Division’s Parent Rights guide covers these). There are also vouchers available if parents decide to send their kids to an independent school and fund the tuition themselves.

But Lynne Loeser, statewide consultant to the Exceptional Children’s Division at the Department of Public Instruction, added that parents should think hard about leaving the public school system because doing so means walking away from the rights afforded under federal laws that protect students with disabilities.

“When you go to a private school, you’re losing that access to some of those hard-fought rights that you have under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act,” she said. “So, you know, I am an advocate, with 40-plus years in the public schools, and I’m also very supportive of places like The Hill Learning Center in Durham. I think there’s definitely a place for places like that. And, I think that they have advantages of being able to give that really small group time, intensive intervention to bring kids up to speed.

“But I think that this is a very personal, emotional decision where parents have to weigh out when they need to access something in addition to or in replacement of public education. Within IDEA, they talk about if the child has needs a public school just cannot meet, but that’s really at the point of where the public schools fail to be able to meet that child.”

What if you’re at that point? Or if you’re just not satisfied or feeling confident in your child’s public school education?

There are several independent schools dedicated to students with learning differences that specialize in taking kids that are behind grade level and helping them catch up and then continue to grow.

“What I see and hear most is the amount of support is not doing the job,” said Susan Mixon Harrell, executive director at The Hill School of Wilmington. “And having been a public school special education teacher, I get it. The load of students, the needs of students, the student-teacher ratios — it’s just hard to do all that needs to be done for a child who’s falling behind. And that’s the difference here: It’s 4-to-1 [ratio of students to faculty]. You can’t hide.”

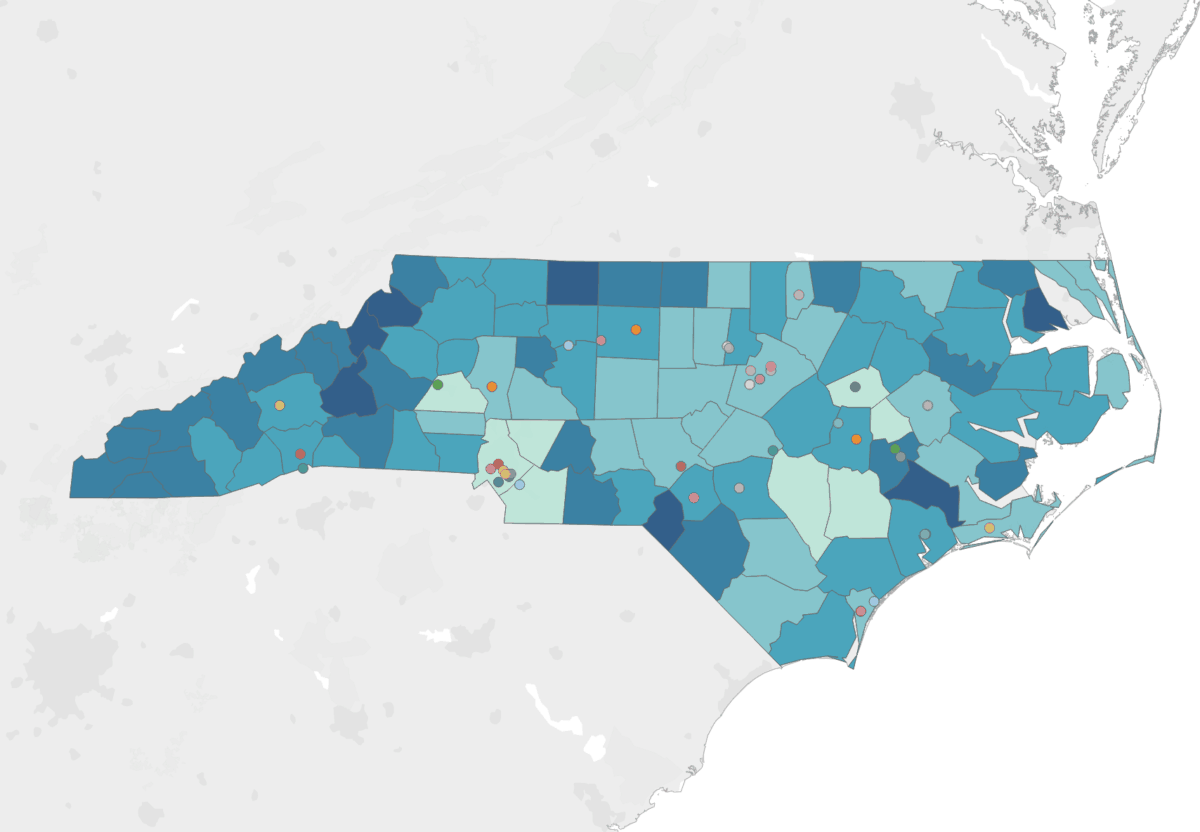

These options, covered in more detail below, are not available everywhere in the state, though. Using publicly-available data, we created the following map designed to show where exceptional children are located in North Carolina and where independent learning differences schools are located.

A couple things about the map: We want your help to identify learning differences schools we may have missed. You can do that through our Reach survey below. Second, this data is not sorted by district or LEA — but rather by county in order to show the geographic locations and concentrations of children identified by the state as having learning disabilities. The county data displayed when you hover over a county includes traditional public schools and charter schools. The pins represent independent learning differences-focused schools in the state.

Private schools focused on learning differences in North Carolina have several things in common: They are set up to give kids a place where they don’t feel different from their peers. Many of these schools offer smaller classes and a lower student-to-staff ratio than public schools. Teachers are specially trained to work with students with learning and attention issues — and many have certifications or master’s degrees in special education. Often, speech-language pathologists and psychologists are on staff.

“There’s a combination of benefits — at the social level of students realizing they’re all in this together where everybody else has something that they’re working on too and reaching them through instruction that’s designed for them,” Mixon Harrell said.

The student-to-staff ratio is often stunningly low for parents who are accustomed to public school student-teacher ratios. But independent school educators say the benefits go beyond smaller class sizes. Knowing that the student population may have things in common — such as attention issues — allows these schools to design classrooms and curriculum that go beyond accommodation and allow children to thrive.

This can be as simple as having bands at the bottom of students’ chairs so they can wiggle their feet when they are feeling fidgety or prone to distraction, or having kids stand up and do jumping jacks while spelling words to address their need for movement while working on neurological connections.

There’s also curricula specifically and intensively designed for students whose brains are wired differently. Some schools develop and use their own curriculum, like The Hill Learning Center in Durham, whose instructional model and materials are only available there and at the affiliate schools in Wilmington, Greenville, Colorado Springs, and Geneva, Switzerland.

Other schools, like The John Crosland School in Charlotte, emphasize alternative instructional and assessment methods and incorporate technology and the arts. Still others, like The Fletcher Academy in Raleigh, use personalization as a driving organizational principle. Prior to each school year, the school individually prepares each students’ course schedule to match their ability level and goals.

Another advantage of these private schools — one that would be unfair not to point out because it is not a widely available option for public schools — is the school’s ability to select its student population. While independent schools are often set up to address additional needs of students with learning differences, they also have the ability to not accept certain children with behavioral issues if they would not thrive under that school’s instructional model or would distract other students.

“In public schools, you have to take everybody and you have to try to help everybody,” said Mixon Harrell, who has worked in the field for about 40 years and previously was a special education instructor in the Wake County Public Schools System. “And we don’t. We have a group of psychologists who review our applications and give their recommendations to us on the administrative team about who seems to be a good fit.”

All of these factors combine to create an environment, social structure, and learning process that often benefits students who are behind grade level or struggling with standardized education. But, of course, it does come at a cost. While many parents say it’s worth it, financing private school for extended periods may just not be an option if your child does not get full or partial funding through the district or a voucher program.

Fogg reminds parents that it does not have to be a permanent solution.

“In our office, our goal is to make sure the student can get the instruction they need in the public school system, because that’s the least restrictive environment. That’s where you’re around your non-disabled peers,” she said. “Now, I’ll absolutely say that, particularly when I was in private practice, I advocated for private school placements frequently with the hope that, if it did actually happen, after two or three years, the student had gotten the instruction that they needed and then they returned to the public school and they were able to be in the regular education classroom and continue to move forward and keep up with their peers. Were they always 100% on grade level? No, but they were in a much, much better place than they were when they left.”

Aside from funding, one major issue for parents interested in independent schools is access. As the map above shows, there are resource deserts where few options exist in close proximity to where exceptional students live.

“One thing that’s a big problem is that in the rural areas, there’s often not a private school option,” Fogg said. “If you think of North Carolina as a pie, it’s the pie crust. It’s the ones along the borders, really, who are the ones that have the least amount of services.”

One way to address lack of access, Fogg says, is to bring the independent school-style instruction to the public schools.

The state is taking steps toward that, one way being through the North Carolina State Improvement Project. But teachers, schools and school districts can — budget permitting, of course — find their own training. For example, The Hill Learning Center partners with some 30 school districts and has trained hundreds of North Carolina teachers to help implement their HillRAP Digital and the Hill Learning System program in those schools. Another example is the free training available through the Friday Institute’s MOOC-Ed.

“Really what should happen is the school system should really get its teachers trained in the methodology that the private schools are using,” Fogg said. “And they should really create classrooms that have the small student-teacher ratio, and the teachers with the training and experience to do the same thing they’re doing at the private school. Obviously, that’s very expensive and a lot of schools don’t do that.”

Recommended reading