The policy for identifying and evaluating students for special services through the state’s special education program may change when the State Board of Education meets on June 5.

The changes are intended to address stakeholder concerns, but practitioners who help kids qualify for specialized services say it may not improve the identification of children with special needs.

The draft policy addendum can be found here, and the public can comment on it by using this link until May 29.

Original policy written four years ago

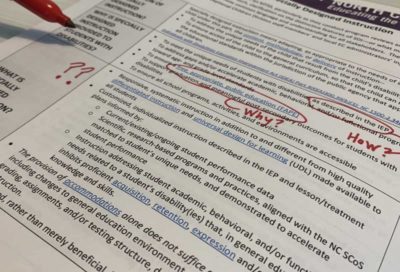

The amendments are to a 2016 policy, which was drafted by the Department of Public Instruction’s office in charge of special education, the Exceptional Children Division. That policy signaled a move away from a method for identifying specific learning disabilities – something called “severe discrepancy” – and instead focusing on a child’s response to “scientific, research-based intervention.”

“Severe discrepancy” looks at a variance between a child’s intellectual ability and academic achievement. In a 2015 white paper, a DPI Specific Learning Disability Task Force said, “Although the IQ-achievement discrepancy model has been the cornerstone of SLD determination nationally for over thirty years, there has been, and continues to be, significant criticisms surrounding its efficacy and efficiency in classifying students with SLD.”

In presenting the policy amendments to the State Board in May, Matt Hoskins, the Exceptional Children Division’s assistant director, called the original policy a “wait to fail” model. Since that 2016 policy was adopted, the EC Division has been introducing and training districts on using its response-to-intervention model, which uses a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) approach. This approach involves testing, assessment and observation to collect data that inform whether a child qualifies for EC services.

A third model for identifying specific learning disabilities is called “patterns of strengths and weaknesses,” but the state’s policy prohibits using it.

Changes stem from four years of feedback

In the course of training on implementation of response to instruction and intervention, the EC Division heard concerns from stakeholders about specific language in the 2016 policy. The division called out three major areas of concern during its report to the State Board in May:

- Lack of clarity on what “research-based” intervention means;

- A discrepancy between how federal laws define specific learning disability, as a “disorder,” and what the 2016 policy says, a “disability”;

- Inclusion of language allowing comparisons among culturally and linguistically similar peers.

In response to feedback since the policy was adopted, division leaders met with stakeholder groups in January. The amendment sets a threshold for “research-based” and removes a provision that required at least two interventions for evaluation. Hoskins told the State Board that the division found no significance to the need for two interventions.

The amendment also removes language around cultural and linguistic comparisons. EC Director Sherry Thomas said that language had been intended to distinguish between children who had specific learning disabilities and those with other issues — such as language acquisition challenges for English language learners. But she acknowledged stakeholder concerns that the language could be confused or misinterpreted to make it harder to identify and serve students in racial and ethnic subgroups.

Practitioners say the amended policy could still leave students without needed services

The federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act enumerates several categories of students who would qualify for assistance, including those in the “specific learning disability” category. Specific learning disabilities include such things as dyslexia and dysgraphia. Advocates in North Carolina say the state is not doing enough to identify and serve all students with specific learning disabilities.

“The system is set up to make it harder for kids to get services,” said Ginny Sharpless, founder of Dyslexia NC and one of the stakeholders who met with the EC Division in January. “Parents feel like they have to sue their school [district] just to get the help their kids need.”

Under the amended policy, lawyers at Disability Rights NC say, identification won’t get easier.

“In order for a kid to be found eligible under SLD using this policy, the school/district must know how to deliver appropriate instruction, implement evidence-based interventions, and appropriately document that,” attorney Reighlah Collins said in an e-mail analyzing the policy amendments for EdNC. “Many districts we interact with don’t know how to do those things and the consequence is that kids in those districts really can’t be identified as SLD (at least not by actually following the Policy) because there won’t be the data to back up an eligibility determination.”

Collins said students could be misidentified with intellectual or emotional issues that would not qualify them for the EC services they actually need.

Collins applauded some changes, such as more specifics about “evidence-based intervention” and removal of the “culturally similar peers” language. She also called removal of language that said a disability “substantially limits academic achievement” was a positive.

But she pointed to several remaining issues:

- The amended policy requires “intense” documentation of insufficient rate of progress: “Some of the districts we’re in don’t have this type of documentation and have significant difficulties providing evidence-based instruction.”

- Districts that can’t implement or appropriately document use of evidence-based interventions (RTI/MTSS) “are going to make it super hard for kids to get identified as SLD.”

- Collins believes the amended policy could be interpreted as requiring students to move through and fail every level of MTSS before being identified, “which could really delay identification.”

- Twice exceptional kids – kids who are both academically gifted and have a specific learning disability – won’t be found eligible under the policy. These kids, and even kids with specific learning disabilities who have average IQs and found successful coping mechanisms, would be under identified and underserved.

Much of the concern is at the district and charter school level, specifically a district’s ability to carry out the policy. For its part, the state believes both the policy and the guidance it offers local education agencies can set up children for adequate supports.

“The changes [to the policy] take into account a lot of stakeholder input,” Thomas said. “And there is a lot of guidance we are providing to LEAs, as well, to ensure sound decision-making for evaluation and eligibility decisions.”