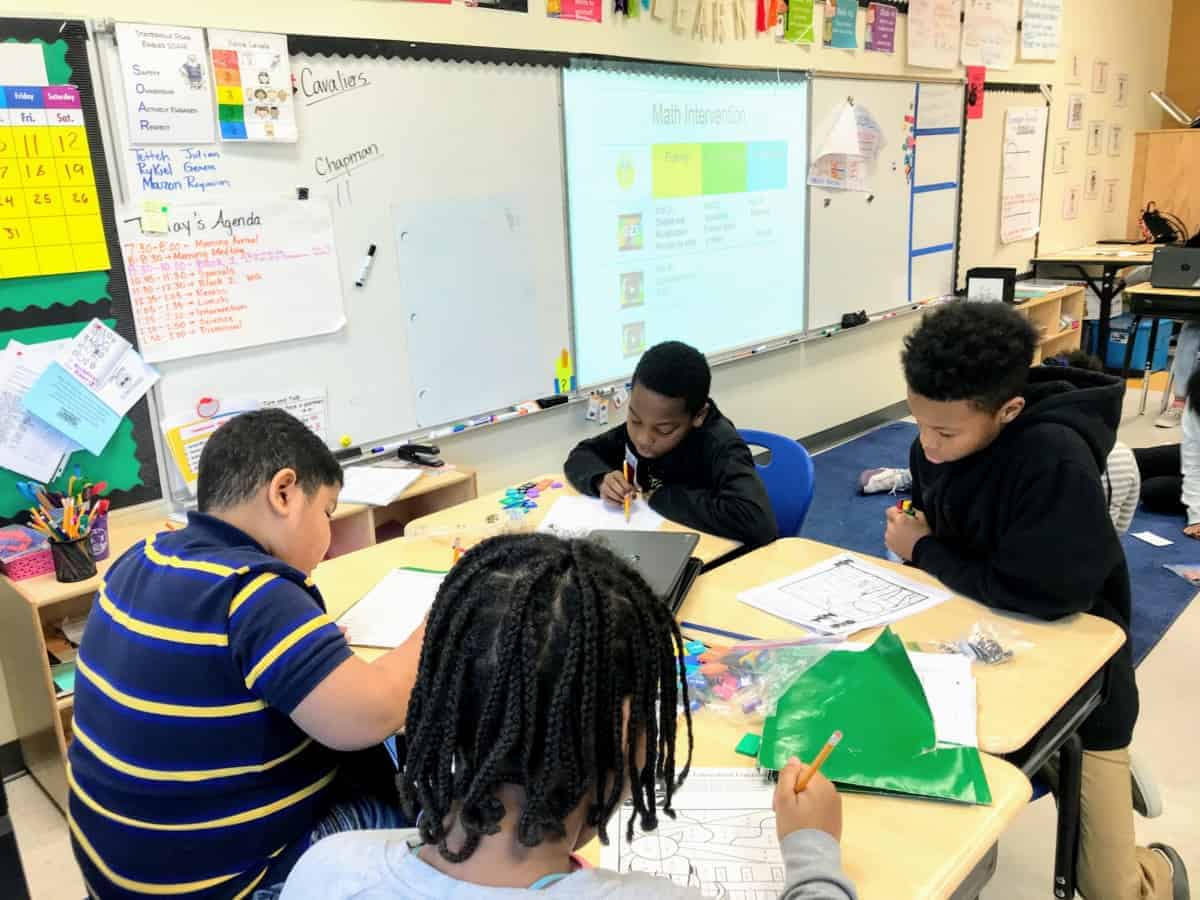

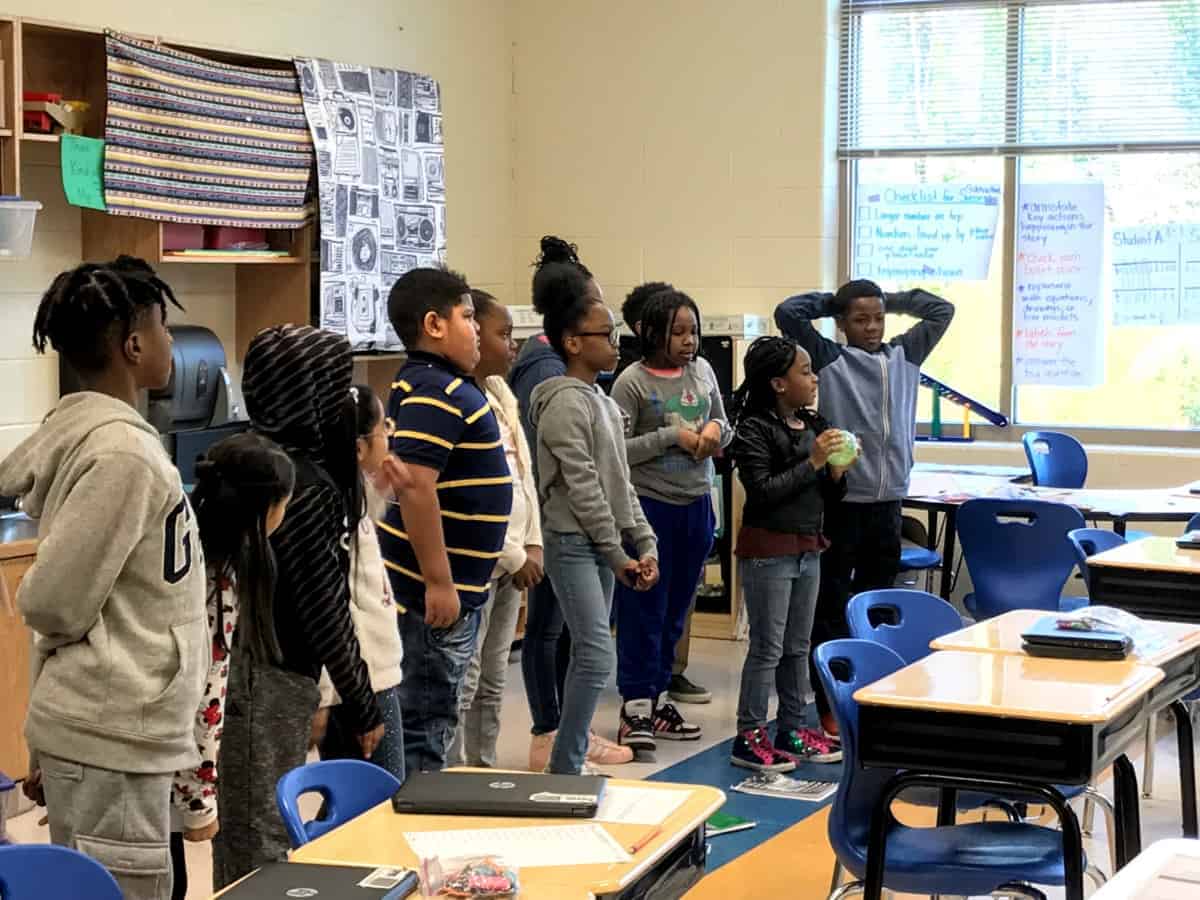

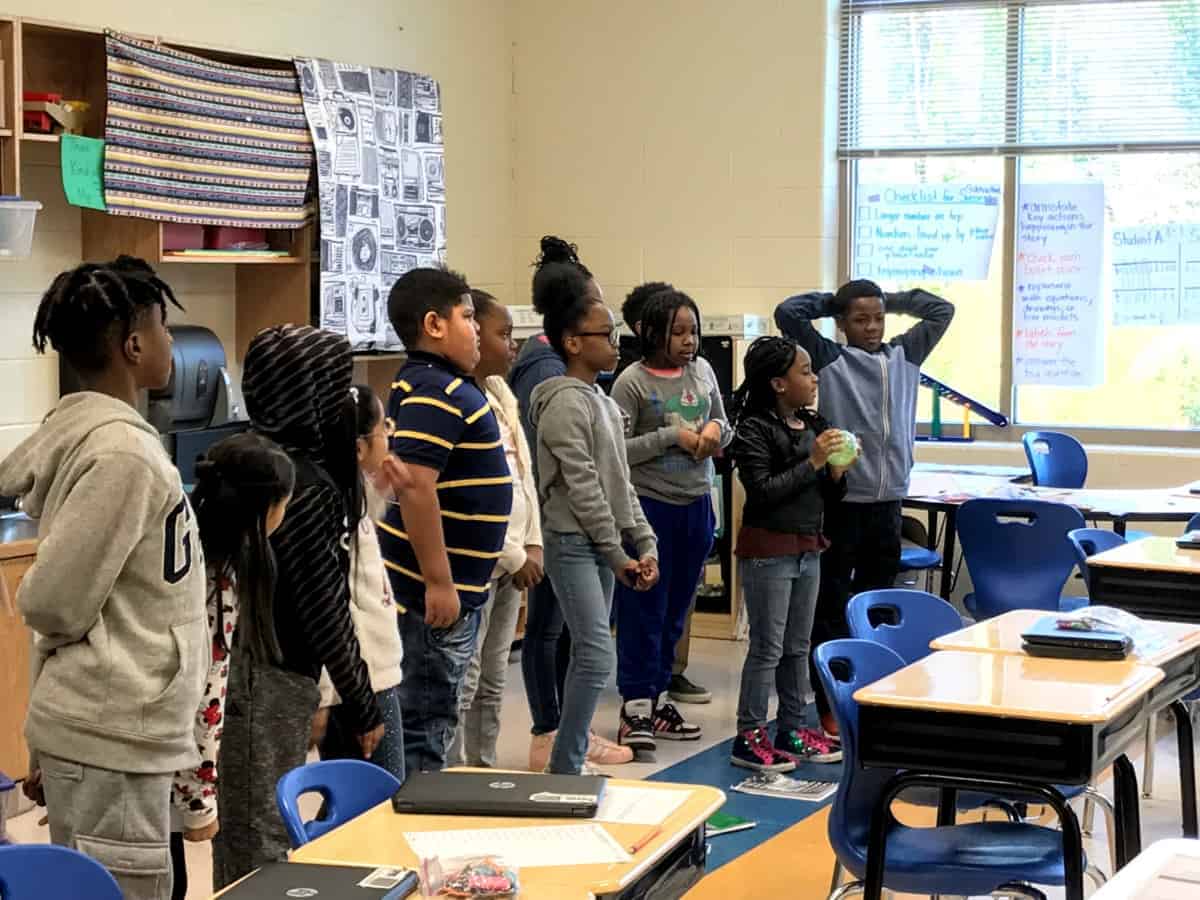

“How do you know those are equivalent fractions?” fourth-grade math teacher Ashley Chapman asked a small group of students at Statesville Road Elementary School in Charlotte.

“We know they are equivalent because they take up the same amount of space,” a student named Dream responded.

As Chapman continued working with the small group, the rest of the class worked on assignments independently. After 10 minutes, a timer went off and a new group of students joined Chapman at her table.

Chapman is in her first year teaching fourth grade in North Carolina. She is part of the first cohort of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools’ (CMS) new Teaching Residency, an alternative licensure program for college graduates. For Chapman, who was a teaching assistant in New Orleans before she moved to North Carolina last spring, it was the best way to get her certification without spending the time and money to go back to school.

CMS is the first school district in North Carolina to offer its own teacher residency after the General Assembly made changes to teacher preparation pathways in 2017. Among other things, SB599 eliminated the lateral entry pathway and replaced it with the residency model. It also opened the door for organizations outside of colleges and universities to become educator preparation programs (EPPs).

The lateral entry pathway provided a way for mid-career professionals to enter the classroom and teach while obtaining their teaching certification. Similar to this, the residency model outlined in SB599 is designed to get college graduates in the classroom while they work on their certification, but it has a few more requirements.

To receive a one-year residency license, renewable twice, candidates must have a bachelor’s degree or higher, be enrolled in an educator preparation program (EPP), and pass the required certification tests. The law also stipulates that residencies must be a year at minimum, and EPP’s must provide ongoing support for the duration of the residency. That support includes a clinical mentor, or a teacher who provides supervision and support, for each resident.

When the legislature passed SB599, CMS was in the middle of talks with The New Teacher Project to partner to develop a teacher pipeline with funding from the federal Supporting Effective Educator Development (SEED) grant program. After learning about the new residency requirements, CMS decided to apply to become an educator preparation program and create a teacher residency program based on the requirements in the new law. The first cohort of residents is now teaching in CMS schools, and CMS is recruiting for an expanded cohort next year.

To apply, candidates must have a bachelor’s degree with an undergraduate GPA of 2.7 or higher and pass the state-required certification tests. Those who are accepted complete a six-week training program over the summer and then can be hired by CMS schools. Over the course of their first year, the teachers take online modules similar to college-level coursework and receive coaching and support through the program. At the end of the year, teachers can receive their license if they have met all the requirements.

Shannon Stehmeier, CMS Teaching Residency Specialist, said the goal of the residency is to address three critical needs: the overall teacher shortage, the lack of diverse teachers, and the lack teachers in specific content areas like elementary and secondary math and English. Of the 45 residents now teaching in CMS schools, the majority are nonwhite, Stehmeier said.

The residency also allows CMS to cultivate a pipeline of teachers that are trained in “the CMS way.”

“We want to create our CMS way within the teachers,” Stehmeier said, explaining how the training that residents receive in the summer and during their coursework is aligned with the district’s approach. “All of the coursework that we are creating has to be submitted and approved by the state, but I’m working with the course writers to make sure that CMS is aligned throughout.”

The residents benefit from this streamlined approach as much as the district does.

“Collaborating with people who are in the CMS system made me aware of things that were going on in North Carolina,” said Chapman, “but also just the systems that CMS has that were different from where I was before.”

One of the most valuable parts of the experience for Chapman was the six-week summer training program. Chapman spent the first two weeks of the program with the other residents in class themselves, learning instructional techniques and behavior management.

“One thing that I really liked about each of the instructors is that the instruction style was similar to what they had in their own classrooms,” Chapman described. “They were really modeling what top quality teaching looked like.”

For the next four weeks, they spent half the day teaching and the other half in class. Chapman explained the importance of getting that clinical practice during the summer to help the residents understand what teaching is really like: “Thinking about teaching and actually teaching [are] two different things. Going to a school play is different than sitting in a classroom and seeing the inner workings of being a teacher.”

She added that clinical practice is helpful in weeding out people for whom teaching is just not a good fit. “I think the work load is similar to what teachers would expect during the year,” she explained. “If you can’t handle it during the summer than you probably couldn’t handle it during the year.”

The numbers bear that out. According to Stehmeier, of the 82 people that started the summer program, only 48 completed the six weeks. Forty-five of the 48 passed their certification exams and were hired by CMS.

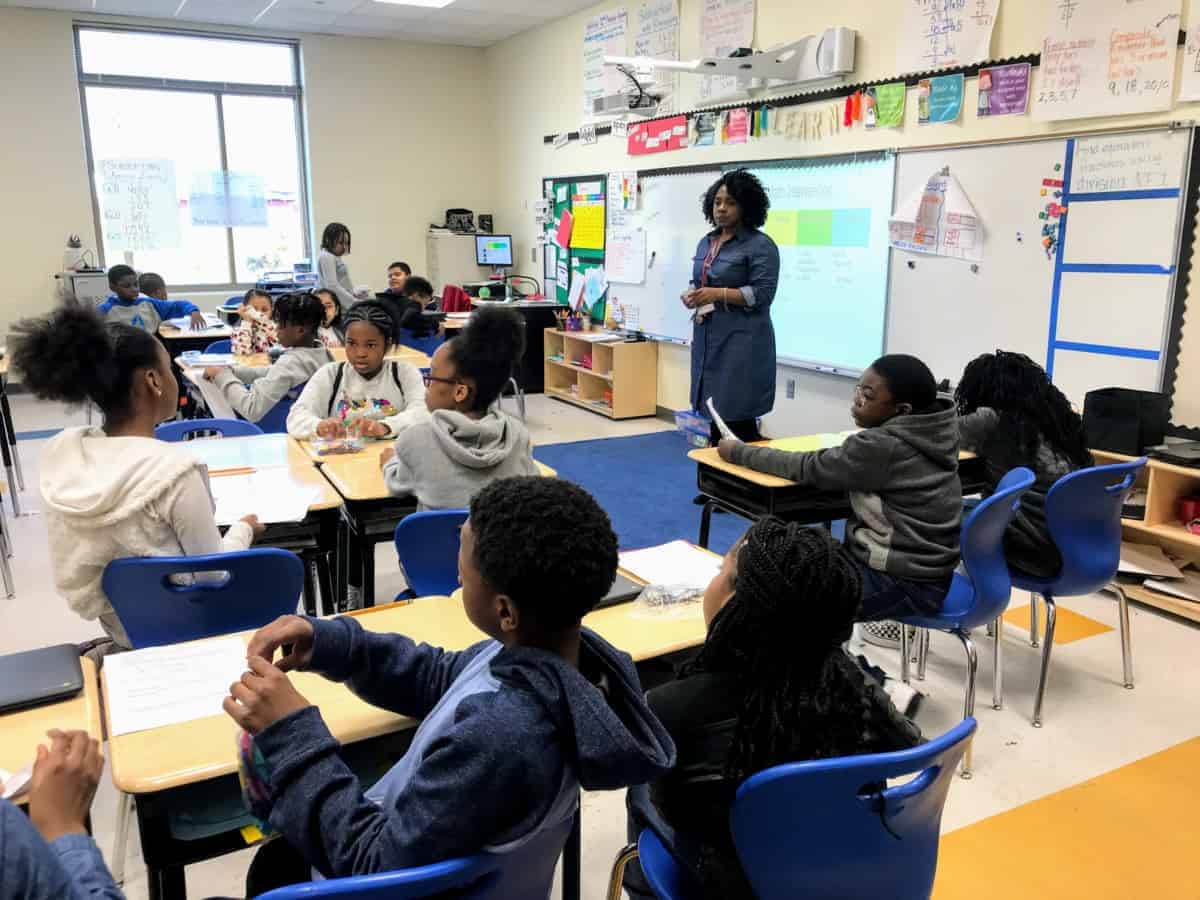

Residency does not end once the residents are hired and start teaching; it has only just begun. Throughout the year, the residents complete college-level coursework in a series of modules. For each module, residents have to submit various assignments, including sample lesson plans and videos of them teaching and interacting with students.

“They do everything from lesson planning, videoing, guided reading lessons, and small group lessons,” Stehmeier explained.

The residents are graded on their modules and have to pass the coursework in order to get a certification at the end of the year.

Each resident also has a coach who visits the resident six times over the year to observe and give feedback. The coaches are available to answer questions, brainstorm new instructional strategies, and generally help the residents in any way they can.

Chapman’s coach, Chris, visits her classroom once a month, and they also have phone conferences. He gives her feedback and helps her prepare for edTPA, a “performance-based, subject-specific assessment” that all beginning teachers in North Carolina must pass to receive their licensure starting on September 1, 2019.

This year, the coaches are TNTP employees, but starting next school year, CMS will be in charge of the coaching. They are exploring different coaching models, but Stehmeier is hopeful they can identify teacher leaders in the district who can serve that role.

Stehmeier is excited about the future of the teaching residency. Right before Christmas, the district asked them to increase their numbers to 110 residents next year, a big jump from this year. They are restructuring a few things based on lessons learned in their first year, including requiring candidates to pass their certification exams before starting the summer program and increasing transparency about the amount of work required to earn their certification.

“This year with this cohort we are going to be very clear and open about the time [commitment],” Stehmeier said. “You are taking college level courses. You are basically in grad school. You are doing work at weekends or at night along with your teaching. …We’re not just going to recommend you for licensure just because you are here. It is very rigorous and we do not pass everybody.”

Stehmeier also said they are going to work on stronger communication between principals, coaches, and support staff. “I’ve got to come up with a platform for the total communication between principals, support staff, and our coaches,” she said. “We’ve got to make sure the work is aligned.”

To measure their success, they will be looking at everything from surveys to EVAAS data and student performance data to observation scores. And as CMS continues to grow, the teacher residency will reflect that growth.

“Being able to go in and revise the coursework and revise what our expectations are for the residents is critical for me,” Stehmeier said. “Our district is in such a growth period. It is going to be beneficial to us to really teach them the CMS way instead of having them have to go back and relearn things.”

When asked if she thinks other districts will follow suit, Stehmeier said she thinks it’s an amazing opportunity for any district. “I think it’s good for any district. You can focus on your needs, and you can grow with the district.”

Chapman said she sees the value in this model and thinks it is a good option for getting college graduates like herself who have not gone through a traditional teacher preparation program in the classroom with plenty of support in their first year. And from the number of students who told me how much they like her class, it seems that Chapman is well on her way to becoming a successful teacher.

This article is part of a series on clinical practice, the hands-on, real-life experience in a classroom during an educator preparation program. Part One gives an overview of clinical practice, including how programs across North Carolina are honing their approaches to clinical practice partnerships. Part Two explores the clinical practice experience of students at Elon University.