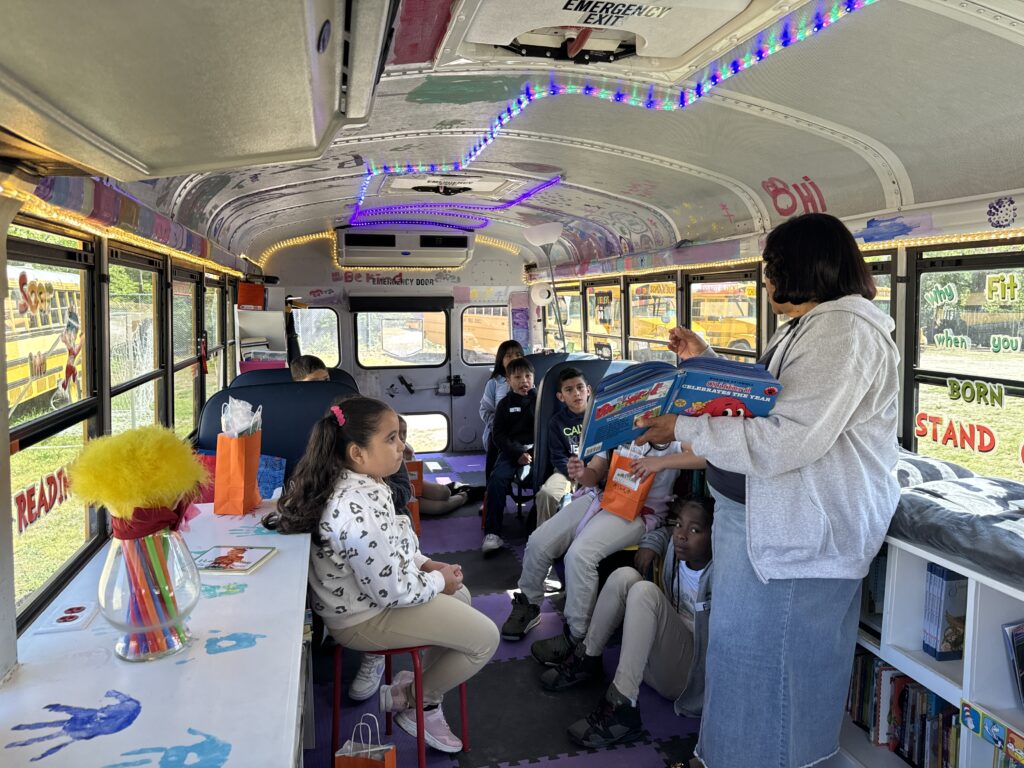

At Reaching All Minds Academy, a STEM-focused Durham charter school, students grow and study plants in a decommissioned school bus, which has been converted into a mobile greenhouse. The school’s “educational bus fleet” now also includes a podcast studio and library bus, highlighted in a recent school video.

More buses are coming. An aquaponics lab, in which plants and vegetables are fed through wastewater from a fish tank, is under development, as is additional classroom space, according to Thomas McKoy, the school’s principal.

“Innovation: That’s what we’re here to do,” McKoy said.

His school’s ingenious ideas are attracting national attention. In 2025, Reaching All Minds Academy (RAMA) received a 2025 national impact award from the nonprofit organization Building Hope, specifically for educational innovation.

“You see it happening nationwide, you see it happening locally within our state,” McKoy said. “I would just push or challenge the other charters to add that into their mission, to continue to innovate for our students in North Carolina.”

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

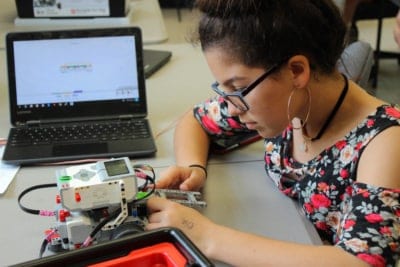

State lawmakers first approved a system of public charter schools in 1996, outlining six core purposes in statute. Purposes include increasing teaching or learning opportunities and expanding parental choice. Notably, lawmakers also charged charter schools with encouraging “the use of different and innovative teaching methods.” Aspiring charter leaders must specify in their application how their school will fulfill one or more of these legislative purposes.

Now, nearly 30 years after the law’s passage, 213 charter schools are operating statewide during the 2025-26 school year, according to the state’s Office of Charter Schools (OCS).

In addition to RAMA and its enterprising bus fleet, how are other charter schools driving innovation? Take a look:

- Union Day School (UDS), a K-12 charter school in Weddington, promotes accessibility in advanced coursework by providing International Baccalaureate (IB) programming to every middle and high schooler. According to UDS, the school is the first and only North Carolina charter with an approved IB program.

- Northeast Academy for Aerospace & Advanced Technologies (NEAAAT), an Elizabeth City charter school, creates myriad real world learning opportunities for students in grades 5-12, helping them develop the “mindsets, skillsets, and toolsets” that position them for success in college and career. NEAAAT has also garnered national attention, and was the focus of a recent spotlight from Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

- Thomas Academy, an alternative charter school in Lake Waccamaw serving students in grades 3-12, integrates classroom instruction with social emotional learning. Students can access therapeutic care or even equine therapy to help them process trauma, if they are recommended for those services. Thomas Academy enrolls residential students living at the Boys and Girls Homes of North Carolina, and also draws students from Columbus County.

Spanning the state, these charter schools serve varied student populations — but all are fostering innovative teaching methods.

Skipping the scrapyard: Aging school buses as emblems of sustainability

According to McKoy, RAMA’s innovative bus program was born from a simple ethos: Serve your community, using what you have.

RAMA currently serves 475 K-8 students. Most of the Title I school’s student population — over 93% — are economically disadvantaged, according to 2024 data.

“We really wanted to show them that it doesn’t take something from the outside or someone else to improve what you have,” McKoy said.

School leaders asked themselves this question, he added: “What do we have on our site, in our building, that we can use to enhance or create value for ourselves?”

The answer, of course, came in the form of those decommissioned school buses. Skipping the scrapyard, school leaders retrofitted them for educational impact.

The educational bus fleet is also aligned with RAMA’s emphasis on sustainability. Leaders utilize resources “to the full extent,” McKoy said. That includes “reducing waste — physical waste and also monetary waste,” he added.

Another RAMA initiative transitioned the school from single use lunch trays to washable trays. RAMA is also involved in a major recycling program and has adopted the highway in front of its campus, McKoy said, with a focus on reducing environmental impact.

As the bus fleet expands, these themes persist. The aquaponics lab is a circular system that not only produces vegetables, but also reinforces messages of sustainability, environmental stewardship, and even entrepreneurship.

“That’s something that we work with the kids on: How do we turn this into a business?” McKoy said. “How do we also use this to make money for our school and our educational program?”

Ultimately, he hopes the buses spur creativity and replication across North Carolina.

“It’s not about hoarding it or trying to keep the idea to ourselves,” he said. “No, we really want to see more and more of these… throughout the state.”

Promoting IB accessibility: ‘This is for everyone’

Founded in 2016 as a K-3 campus, Union Day School (UDS) always planned to offer International Baccalaureate (IB) programming beginning in sixth grade, said Joely Lord, the school’s executive director.

Nearly a decade later, UDS, which is located in Union County, serves 700 K-12 students from five counties. Its inaugural cohort of 17 high school seniors will graduate this year, with around 30 juniors waiting in the wings.

A key driver at the school’s inception, leaders said, was making IB programming accessible to the local community.

“The thought… when the school was founded was, ‘We want to bring that to everyone who wants it,’” said Lord. “We have kids coming from Anson County all the way to Weddington for these programs.”

“It really is about trying to make this an equalizer,” she added.

According to Union County Public Schools, IB programming is available at two other county schools, including a magnet school and a traditional district school.

“One of the most important parts of our school is that this is for everyone,” said Graham Foster, head of the UDS upper school. “IB goes out of their way to make sure that schools understand IB classes are for all; they’re not just for the select few. For us as an independent charter school, everybody that comes into our building — middle and high school — are IB students. Everyone.”

Preparation for IB programming at UDS begins early. Spanish instruction starts in kindergarten, and inquiry-based science begins “very early in lower school,” said Lord.

UDS secured authorization for its Middle Years Programme (grades 6-10) in 2023, and the Diploma Programme (grades 11-12) in 2024.

According to the most recent report to the N.C. General Assembly on broadening advanced coursework participation, 66 schools offered IB programs in 2024; nine more were candidate schools in the queue. Most IB-authorized schools in North Carolina — 93% — are public, according to the report.

Travel abroad enhances the school’s robust IB curriculum. Each year, a high school group from UDS travels to Spain for 10 days of language and cultural immersion.

Increasingly, international students are drawn to UDS and its global mindset, leaders said.

“The last time I checked, we had 11 different languages spoken here,” said Lord.

Read more

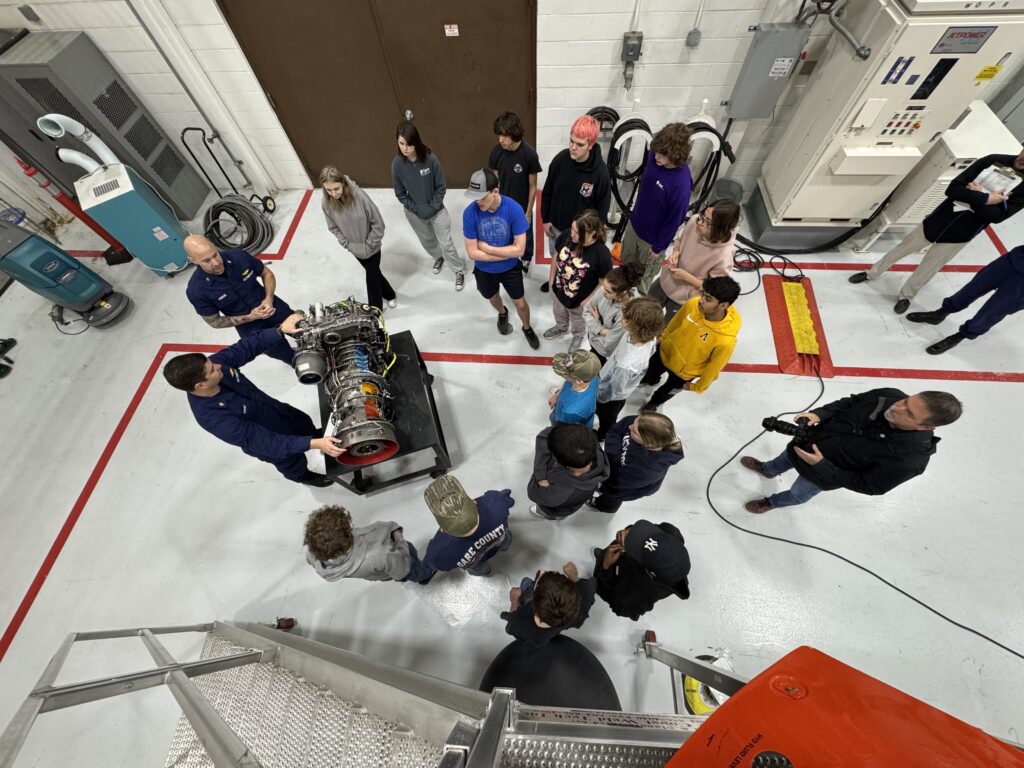

Developing competency: The role of real world learning

At NEAAAT, students pursue a STEM curriculum and project-based approach to learning. In high school, they earn certifications in aviation science, computer science, or health science — and can begin college coursework as early as ninth grade. As juniors, they can pursue dual enrollment at a local college. Students also participate in business internships and complete community service hours, all aligned with NEAAAT’s comprehensive Portrait of a Graduate.

A Title I school in the northeastern corner of the state, NEAAAT serves 770 students from eight counties.

NEAAAT’s mission pivots around competency and what CEO Dr. Andrew Harris describes as “anytime, anywhere learning.”

Some learning necessarily occurs within the worlds of work and higher education. The goal, Harris said, is for students to “experience what life is like after high school — before graduation.”

“For us, the future of education is all about real world learning taking place in every classroom, every day — the idea that a whole lot of learning takes place outside, beyond school walls,” he added.

Curriculum is thus influenced by partnerships with local employers and higher education institutions.

“Part of what charter school autonomy and flexibility allow is for us to work directly with our local employers to shape courses that are designed to meet their needs and prepare our students for high-wage, high-demand jobs that are available right here in the region,” Harris said.

Accolades for the school are also stacking up. NEAAAT is the recipient of a 2025 Building Hope award for student empowerment, was a 2024 Yass Prize semifinalist, and was one of 10 North Carolina schools recognized by the Canopy Project for innovation.

In June, NEAAAT was also chosen to join the Future of High School (FHS) Network, one of just 24 schools or systems nationwide. The FHS Network “embraces a new education architecture built on a competency-based model that prioritizes meaningful learning over seat time,” according to its website. In North Carolina, the Mooresville Graded School District is also participating.

Harris hopes the initiative will guide a new and meaningful approach to student assessments.

“We’re working with thought partners all across this country to really think about and build solid evidence for next-generation assessments that evidence student learning in ways that show not only what they know — but what they can do with what they know,” he said.

Read more about NEAAAT

Fostering uplift: Integrating instruction with social emotional learning

A Title I school, Thomas Academy provides students with an individualized education in small classes, all while leveraging a social emotional learning model. The school’s approach is oriented around students who haven’t succeeded in traditional learning environments. In addition, if students need therapy for traumatic experiences, clinicians are on site to provide that, said Dr. Cathy Gantz, Thomas Academy’s principal.

Currently, Thomas Academy serves 75 community and residential students. The school is located on the grounds of the Boys and Girls Homes of North Carolina.

Grade-level offerings at the school are growing. Recently, Thomas Academy secured approval from the state’s Charter Schools Review Board to add third, fourth, and fifth grades this year, in an attempt to increase Average Daily Membership (ADM) and boost funding.

For accountability purposes, the school operates under an alternative charter designation. In order to qualify for that model, at least 75% of high school students must be identified as “at risk” of academic failure, according to state regulation.

At Thomas Academy, teaching methods are holistic in nature. For the past three years, the school has utilized the Teaching Family Model (TFM), developed through the Methodist Home for Children. TFM informs teaching interactions, Gantz said, helping students acquire five basic skills:

- Asking permission,

- Accepting no for an answer,

- Accepting feedback,

- Following instructions, and

- Developing greeting skills.

“A common misconception” is that every youth knows how to behave in the classroom, Marcus Fair of Methodist Home for Children noted in a video about TFM. Some home environments, he explained, may not foster development of these skills.

TFM thus “changes the behavior of teachers,” said Gantz, as they guide skills acquisition. The model also involves “catching boys and girls being good,” she added.

Teachers gather data through a point system, both positive and corrective, Gantz said. Incentives, reflected in a “menu of reinforcers” established by student government members, serve as behavioral motivators. A weekly incentive could include an ice cream party, Gantz said, while a monthly incentive might be a field trip.

A farm across the street from Thomas Academy also offers equine therapy for students recommended for it based on traumatic experience, Gantz said.

Juniors and seniors can pursue vocational classes through a partnership with Southeastern Community College, which uses a mobile classroom to provide onsite instruction.

School leaders also incentivize higher education, providing Thomas Academy graduates with scholarships for college or vocational education. Scholarships extend to graduate school if students pursue a master’s degree, Gantz said, with donors funding the scholarships.

In 2024, Thomas Academy completed an innovative partnership grant focused on school improvement. Recently, the school also applied for a five-year federal grant, Gantz said.

Avenues for growth

Even as North Carolina charter schools deploy a range of innovative teaching methods, a recent report from the Center for Learner Equity (CLE) outlines opportunities for greater impact.

According to CLE, North Carolina does not have a “specialized charter school” focusing specifically on students with disabilities — or serving a “significant proportion” of students with disabilities.

CLE data are from 2021-22, but OCS executive director Ashley Baquero confirmed that no specialized charter schools are operating statewide this year.

North Carolina’s funding model makes launching a specialized charter school difficult, she said.

“I would argue there are structures that impede the development of charter schools designed to primarily serve EC students (Exceptional Children), including the fact that state EC funding is capped and not adjusted for varying levels of need,” Baquero said. “There could also be potential complications with admissions that may not be intentional but could emerge if enrollment is restricted to certain groups.”

While North Carolina does have a few charters designed to serve students in the foster or residential care system, Baquero added, those schools also serve students outside those systems. This helps keep enrollment at a “fiscally viable level,” she said.

In addition, those schools have access to either private funding or resources, such as facilities assistance, Baquero said.

Nationwide, 220 specialized charter schools served students with disabilities in 2021-22, accounting for 2.9% of charter schools, the CLE report found.

In North Carolina, students with disabilities comprised 11.74% of charter enrollment and 14.58% of district enrollment in 2024, according to the state’s annual charter schools report. Both charter and district schools have enrolled higher percentages of students with disabilities since 2022, but the gap between the two models has increased slightly.

“Trends underscore the need for continued monitoring of special education enrollment patterns and targeted strategies to ensure that all students with disabilities have equal access to high-quality educational opportunities, regardless of the institutional model they choose,” the charter report stated.

More broadly, as the charter sector evolves, leaders are optimistic about its capacity to foster greater innovation, with benefits accruing for all public schools and students.

“We really have only just begun to tap into some of the opportunities to scale the innovations that are happening across charters and across other school types,” Harris said. “I’m excited for what that will hold for the future of charter schools, but really for the future of public education in our state.”

Editor’s Note: EdNC has retained Kristen Blair to provide monthly coverage of charter schools in North Carolina. Kristen currently serves as the communications director for the North Carolina Coalition for Charter Schools. She has written for EdNC since 2015, and EdNC retains editorial control of the content.

Two of the four featured schools in this article (NEAAAT and Reaching All Minds Academy) are Coalition member schools.

Recommended reading