Media enthusiasts have a leg up at Davis Drive Middle School in Cary. A green screen studio in the school’s media center enables future filmmakers and weather-casters to sharpen and showcase skills. This year the green screen became a backdrop for student videos featuring science and social studies concepts. Aligned with curriculum standards, videos opened up “another way for students to express themselves,” says Carman Brennan, the school’s media coordinator.

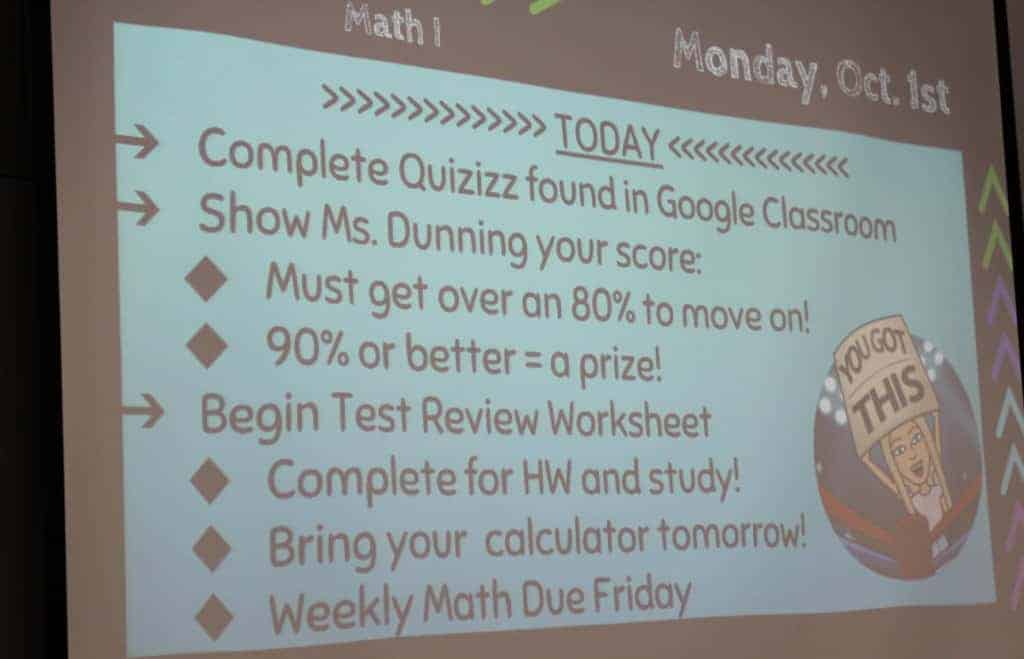

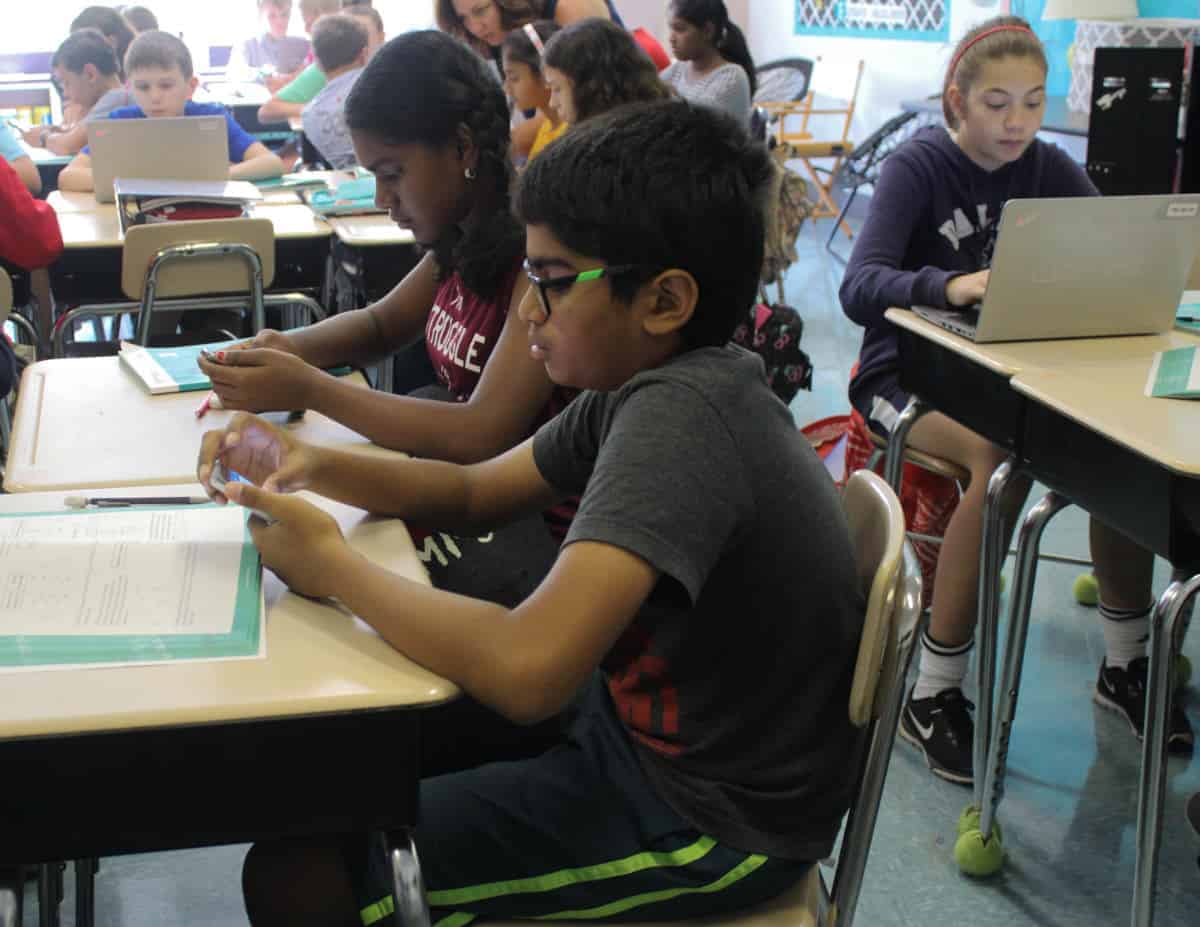

One floor above the media center, seventh-grade math students in Kara Brem’s class are using Seesaw, a platform enabling them to collaborate and create digital portfolios. Nearby, eighth-graders in Katelin Dunning’s math class assess what they know using Quizizz, a public resource they access via Google Classroom.

Students are engaged “bell to bell,” says Rick Williams, the principal at Davis Drive Middle School (DDMS). DDMS, one of 13 Wake County schools to pilot a “bring your own device” (BYOD) program, is now in its fifth year of BYOD and has emerged as a model of successful technology integration. Educators push to grow their skills (a “Williams Winter Challenge” last year promoted Google certification) while integrating technology in a way that is thoughtful, structured, and bounded by limits.

Five months of planning preceded BYOD rollout, says Williams. Guiding integration is a focus on teaching and learning, not the device. “The centerpiece still needs to be the teacher and the instruction,” along with the teacher’s willingness to try something new, says Williams. “It’s not about the laptop or the device.”

Classroom management is paramount. Channeling DDMS’ panther mascot, a system of posted “paw signals” tells students when devices should be out (green) — or out of sight (red). A technology “parking lot” minimizes classroom distraction when devices are not in use, says Brennan.

Integration is closely aligned with classroom goals. When new math concepts are introduced, says Dunning, devices are parked. They come out on practice days or when she wants a quick check of what students know. She monitors student screens closely, trading out personal devices for school devices if alerts pop up frequently.

“It takes more walking around for sure and making sure that they’re doing what they’re supposed to do,” she says, “but most of the time they are. They know the rules, they know what they’re supposed to do, and they want the practice.”

Benefits of digital learning

DDMS is developing best practices on the front lines, but what does research show? Dr. Jenifer Corn, director of evaluation at the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation at NC State University, has served as the principal investigator for state evaluations of technology immersion pilot programs. She has found a consistent increase in student engagement, collaboration, and communication in schools piloting these programs.

“Kids were changing what was going on inside the classroom, creating projects, doing roles. [It] made it more authentic,” says Corn. “The amount and quality of communication between teachers and students, and teachers and parents — it was like a constant flow of communication in a way that hadn’t been happening before.”

The “most proximal outcome,” says Corn, was the change in instructional practices. Teachers relied increasingly on technology to create instructional materials, manage student information, and plan lessons. They assigned more project-based work, and they leveraged technology for assessment purposes, enabling instructional adjustments. Along the way, job satisfaction improved: in 27 of 31 immersion schools, teacher turnover decreased.

Nationwide, rigorous research on technology and learning, especially in K-12 environments, is still emerging. A U.S. Department of Education meta-analysis of more than 1,000 studies, most in higher education or training settings, found that a blended learning approach — incorporating both face-to-face and online learning — had the largest positive effects on student outcomes.

Research on 1:1 laptop programs, which pair each student with a device, shows some benefits. A meta-analysis of 10 studies, conducted by Binbin Zheng and Mark Warschauer, revealed significant positive impacts on English, writing, math, and science achievement. Warschauer, director of the Digital Learning Lab at the University of California-Irvine, has completed numerous studies of his own evaluating laptop initiatives, revealing positive student outcomes in English language arts and writing. But he has not found a consistent link between laptop initiatives and test score gains.

Limitations of digital learning

Warschauer’s research highlights a perennial point of contention: academic outcomes linked to digital learning, when measured by test scores, are often muddled or mixed. The largest study ever conducted of digital learning, published in 2015 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, evaluated technology integration and scores on the international PISA exam for 15-year-olds in 31 countries and economies, including the U.S.

According to the report, “PISA results show there have been no appreciable improvements in student achievement in reading, mathematics, or science in the countries that had invested heavily in ICT [information and communications technologies] for education.” Much more needs to be done, says OECD, noting that “the real contributions ICT can make to teaching and learning have yet to be fully realized and exploited.”

In North Carolina, Friday Institute evaluations did reveal stronger test score growth over time for students in immersion schools, especially in grades 3-8 math and middle school reading. Researchers also found a significant increase in the percentage of economically disadvantaged students in some immersion schools who passed English 1 End-of-Course exams, compared to students in comparison schools. In other states, laptop evaluations show increases in student engagement, technology skills, and self-directed learning. Academic achievement, however, has been mixed.

Why are test results muddled?

“There’s always going to be mixed results. It’s so hard to tease out what the causal relationship is. It’s not just that you’re putting in laptops,” says Corn. “Where the mixed results come from are how the digital devices are used.” Numerous other factors, such as content, leadership, or whether a school has a technology facilitator, also play a part, she says.

Additional research buttresses the importance of how devices are used, especially when they’re allowed in class but not leveraged for structured learning. A 2016 study at the U.S. Military Academy, in which Economics classes were randomly selected to permit or prohibit digital devices, found that students using laptops or tablets earned lower test scores than students using pen and paper. Computer devices “have a substantial negative effect on academic performance,” the authors write, with the caveat, “…We cannot relate our results to a class where the laptop or tablet is used deliberately in classroom instruction, as these exercises may boost a student’s ability to retain the material.”

Frameworks for teaching and learning

So, what kinds of skills do maximize successful teaching and learning? In 2013, the North Carolina General Assembly passed legislation directing the State Board of Education to develop digital competencies to “provide a framework for schools of education, school administrators, and classroom teachers on the needed skills to provide high-quality, integrated teaching and learning.” Competencies took effect last year.

Deborah Goodman, digital teaching and learning lead at the NC Department of Public Instruction (DPI), says DPI has collaborated with partners to build out competencies and create training courses. This summer more than 4,700 teachers attended professional development sessions on digital competencies and Home Base, the state’s instructional improvement system, says Nathan Craver, data, assessment, and continuous improvement consultant at DPI. Student information and technology essential standards, developed a decade ago, are also getting an update; a steering committee is reviewing the standards with today’s digital world in mind, says Goodman.

What informs technology integration in North Carolina’s largest district? In the Wake County Public School System (WCPSS), 150 schools, including DDMS, participate in some form of BYOD. The district is also implementing a digital portfolio initiative, enabling students to retain and reflect on their best work. Two frameworks guide integration, says Marlo Gaddis, WCPSS’ Chief Technology Officer.

The foundational framework is TPACK, representing the technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge educators need to integrate technology wisely and well. “When you use technology for technology’s sake, it can have a negative effect,” says Gaddis. “Technology is not always the answer. We have to be looking at what is the best fit for the task at hand. Think about content first, pedagogy second. The last step is ‘What tools do I need?’ Technology is a problem when we start with the technology tool first.”

Also guiding integration is a “homegrown” framework called DSAP, developed by WCPSS’ Dr. Chris Wasko. “It’s about how you use tools,” says Gaddis. “So often we use tools, and they’re not the right tool for the job.” In Wasko’s model, D stands for delivery, S is for student practice, A is for assessment, and P is for productivity. “What we forget all the time is productivity,” says Gaddis. “Productivity is how we survive every day. How do we create versus consume?”

Ultimately, in a high-functioning classroom, “technology and digital resources are amplifiers,” says Gaddis, expanding and extending the work teachers and students are doing.

Recommended reading