Is there any such thing as the “typical” homeschooling family? Despite abundant, and often uninformed, stereotypes in contemporary culture, homeschooling families today aren’t easily pigeonholed. Some are religious; others are secular. Some are affluent; many are not. Most are white, but a substantial number are black, Hispanic, or Asian.

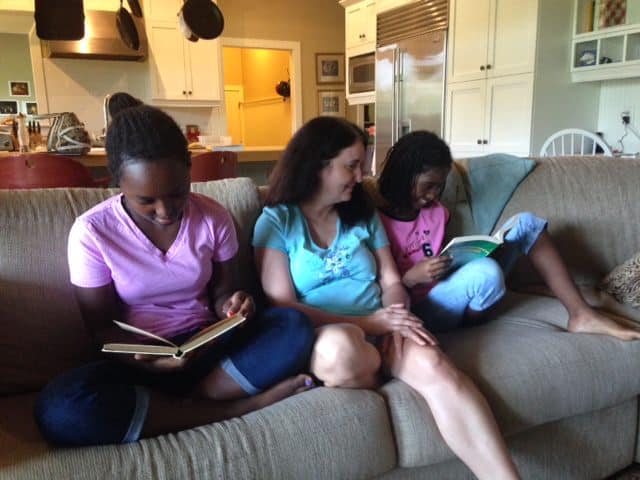

In some homeschooling families, ethnicity is not shared, but a more powerful, and common, identity is. Seven years ago, Herb and Cheryl Whinna, a pathologist and former lawyer, traveled from their North Carolina home to Ethiopia to adopt daughters Tenaye and Wossene, then 5 and 3. The girls, who have been taught at home for the entirety of their schooling, are now entering 7th and 5th grade.

At the epicenter of the Whinnas’ homeschooling decision: inculcating a strong sense of identity in Tenaye and Wossene, whose names are derived from Amharic, the Ethiopian language. “I wanted them to be firmly rooted in who they were as Ethiopians, as adopted into our family, as adopted into God’s family,” says Cheryl Whinna.

Navigating public and private schools for older children Duncan and Megan gave the Whinnas confidence that they could manage homeschooling too. “As [Tenaye and Wossene’s] mom, I felt that responsibility and that privilege…. I wanted to be the primary teacher in their lives,” says Whinna.

A changing movement

Whatever parents’ reasons for choosing homeschooling, one thing is certain: this is no monolithic movement. Dr. Brian Ray, president of the National Home Education Research Institute, has observed considerable change across the years. Homeschooling is “diversifying in ethnicity, race,” says Ray; he estimates that 15 percent of the homeschooling population now is non-white.

As the movement dawned, many homeschooling parents were driven by a “philosophical” or “religious variable,” says Ray. Now, homeschooling has moved mainstream, becoming increasingly secular. Last year, according to NC’s Division of Non-Public Education, a majority of homeschools, 61 percent, still identified as religious, but independent homeschools―39 percent—represented the highest number on record.

Homeschooling continues to appeal primarily to two-parent families in which one parent foregoes work. According to the latest federal estimates from 2012, nearly 620,000 homeschool students nationwide lived in two-parent households with one parent in the labor force.

Yet quite a few families balance work and teaching: in 2012, almost 300,000 homeschool students resided in two-parent homes with both parents in the labor force. And nearly 100,000 homeschoolers lived with a single parent who worked. Most homeschooling families aren’t affluent: more than 60 percent reported annual household incomes below $75,000.

Balancing work and homeschooling

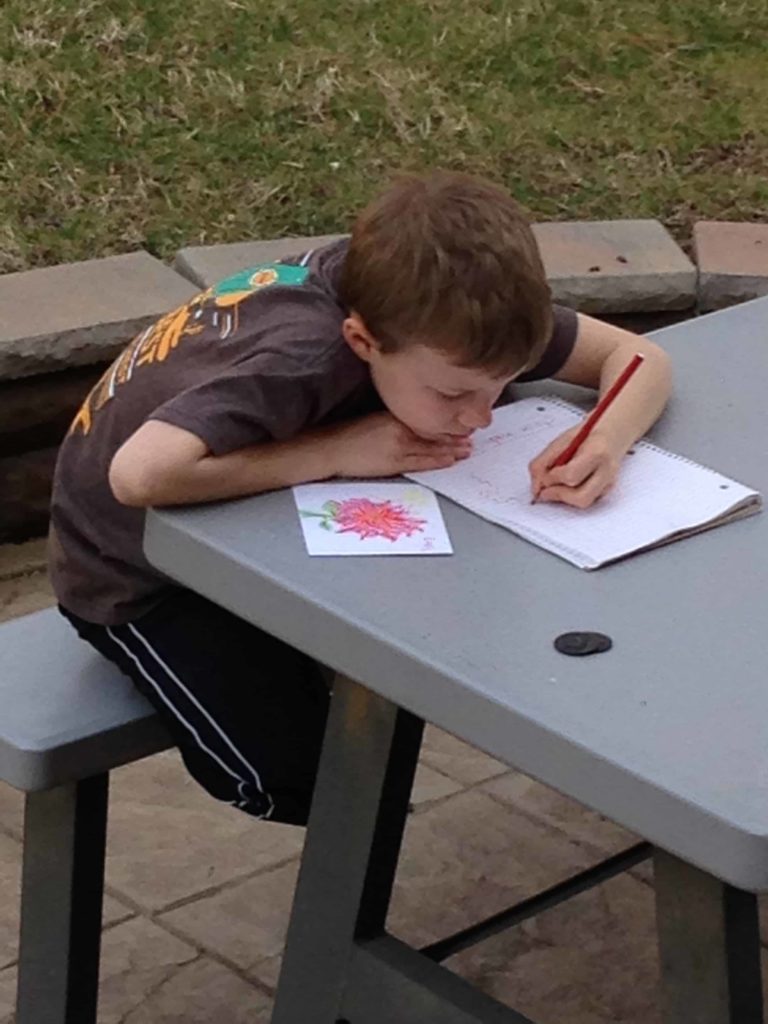

A Wake County mother of two, Kelli Warner is engaged in the ultimate juggling act: working while homeschooling her older son Louis.

Kindergarten and first grade in a magnet school proved a struggle for Louis. He exhibited disciplinary problems, which worsened when Warner and Louis’s father separated. “The standard approach doesn’t work for [Louis],” Warner says. Just before the start of 2014-15, Louis’s second grade year, Warner reached her tipping point, pulling Louis out of school to teach him at home. “I wanted to do homeschooling because he would be with me and I could control his environment,” she says.

Homeschooling’s formidable time commitment has tested her mettle: “I have to work, too,” says Warner, “which makes it hard.” She forged ahead anyway, joining a co-op, soliciting help from a homeschooling friend one day a week, and leveraging online tools to augment her teaching. Activities organized by Cary Homeschoolers, including a visit to a bee center and an insect-finding hunt, added infusions of fun.

Warner’s younger son Jamey has prospered in public school and will return for first grade. But Louis will remain at home this third grade year. “He really enjoys homeschooling,” says Warner.

A grandmother takes it home

For some, homeschooling is a multi-generational enterprise. Jan Chadwick, a former teacher in Durham Public Schools, pulled grandchildren Riley and Corey out of year-round public school in February 2015. Riley, age six, wasn’t reading; Corey, age nine, battled attention deficit disorder, was depressed, and had stopped eating. He told his grandmother, “I’m stupid, I’m dumb, I can’t learn.”

Now, the children, who live with their grandparents, are thriving. Active days are spent learning, tending a tank full of tadpoles, going to zoo camp―all in an immersive “seeing, visiting, touching, smelling” homeschooling experience, as Chadwick describes it. This year, they’ll visit all 100 NC counties. They’ll see “Halifax, the birthplace of freedom,” Chadwick says. And they’ll visit Pembroke, which is “part of their heritage. Their mom is part Lumbee Indian,” says Chadwick.

Chadwick is adhering closely to Common Core standards and wants both children prepared “to step back into a classroom” if needed. But she’s committed to homeschooling: “I’m 71. If I can do it, I would like to take them all the way to graduation.”

Myriad opportunities for outside enrichment

How do homeschoolers handle classes and curriculum? Approaches are as varied as the families themselves. Some parents retain full control over academic instruction, while others tap into a plethora of outside academic enrichment opportunities―from co-ops, to classes, to tutoring.

Drama, club sports, and debate vie for students’ free time. For many, band reigns supreme. Dr. Dennis Renfroe, a music professor at Laurel University, has directed the High Point Homeschool Band for 22 years. Since the program’s 1993 inception, more than 350 homeschoolers have participated in Renfroe’s beginning band and advanced ensemble. Members are devoted, some driving considerable distances. Parents, says Renfroe, have even “turned down job offers” in other states to keep children in the band. “It’s like one big happy family,” he says.

Statewide, homeschooling families are customizing education to fit the dispositions, talents, and needs of individual children. They represent an increasingly diverse movement. Still, they might unite around Tenaye Whinna’s ebullient description of what homeschooling means to her: “You can do as much as you want,” she exclaims. “No limitations!”