Smartphones are teenagers’ constant companions. The last thing teens check at night before drifting off to sleep, phones occupy pride of place in the morning routine, too. Even pillow talk — the digital kind — is common: Many teens sleep with their phones, maintaining 24/7 accessibility for Snapchats, texts, and status updates. Electronic blue light is the 21st century nightlight.

Media multitasking has thus become a near-universal part of adolescence. There’s much to be said for encouraging technological savvy and agility. Teens face a lifetime of digital skills acquisition. Workers know: It pays to be nimble. Literally.

Yet mounting evidence shows constant connection comes with a high cognitive cost. It isn’t making teens smarter, and it’s crowding out things that could.

A reality check on time costs alone: Teens now average nine hours daily with recreational media, according to Common Sense Media survey data. Most aren’t coding or blogging; “content creation” consumes just 3 percent of teens’ digital media time. The primary focus? Entertainment and connection.

Many teens don’t even disconnect for schoolwork. Half use social media and 60 percent text while doing homework, found Common Sense Media. A majority believe multitasking doesn’t compromise their work quality.

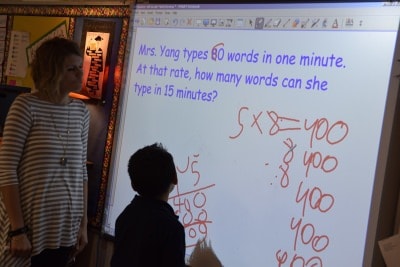

Oh, but they’re wrong. A 2016 study led by cognitive neuroscientist Matthew Cain, published in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, linked heavy media multitasking in adolescents with lower standardized test scores. Frequent multitaskers also demonstrated greater impulsivity and poorer working memory —showing less capacity to retrieve recently-viewed information.

A 2015 University of Connecticut study, published in Computers in Human Behavior, found in-class college multitaskers had lower GPAs; multitasking also increased homework time. Another study from Kent State University researchers found that college students with higher daily smartphone use had significantly lower GPAs — even compared to students of similar academic ability.

Such studies extend earlier findings from psychologist Larry Rosen of middle, high school, and college students. Texting was the top homework distractor; checking social media while studying was linked with a lower GPA, Rosen found.

“Multitasking is a cognitive impossibility,” says Melanie Hempe, nurse, mother of four, and founder of the Charlotte-based organization Families Managing Media. Hempe, who conducts workshops for schools featuring brain research on screens and learning, adds, “When a child has a phone on their desk, it puts them in a different mindset. It puts them one foot in and one foot out.”

Rote work, such as folding laundry, is ideal for multitasking. But complex tasks, such as learning the quadratic formula, require sustained attention. Attempting two complex tasks simultaneously results in “task-switching” not “multitasking,” research affirms.

This is a critical cognitive reality for informing learning, especially since classrooms often teem with distractions. Some school districts have implemented “bring-your-own-device programs,” but scant evidence supports using personal devices such as smartphones in classroom learning. A recent London School of Economics study found test performance in British schools actually rose following a ban on phones. Overall, evidence supports technology integration in classrooms — but with an emphasis on quality, not quantity.

At home, parents can create time and space for real learning. One simple strategy: Separate teens from their phones for homework. Younger teens completing homework on tablets and laptops may need regular monitoring to ensure they’re on task. Parents can also encourage timeless, brain-boosting pursuits such as recreational reading. And at bedtime? Phones and teens recharge best apart.

The mother of two teenagers, I can attest to the efficacy of these strategies for improving rest and learning. Outraged teens might claim you’re ruining their lives. Mine did. But their bodies and brains will tell you otherwise.

Recommended reading