It’s no secret that North Carolina has a long history of policy making that values education. You can look at our history of elected officials, business people, and community leaders crossing political divides to improve the lives of future generations.

We—as a state—have understood the importance of education across the continuum of an individual’s life. From zero to adulthood, education is a bulwark against poverty and a launching pad to economic security.

But education policy and decision making should not—cannot—exist in a vacuum, made in isolation from the multiplicity of factors that may affect a student’s life outside the classroom.

State law in North Carolina mandates that schools deliver 1,025 hours of instruction. That means in a calendar year there are 7,735 hours when a student is not receiving instruction.

That’s 7,735 hours when a student is sleeping, eating, playing, socializing, and dreaming outside of the classroom.

Yes, it is vitally important that we find the right way to measure our students’ academic growth. It is crucial that we continue to adequately support and value our teachers. And we must equip our classrooms with the resources to prepare the next generation workforce this state will need to be competitive in the economy of tomorrow.

But we also must be honest that those issues alone will not guarantee success for all children in the classroom.

The North Carolina Community Development Initiative (CDI) will be launching their new website soon. It’s a project we at EdNC have been a part of and it has been a reminder of how many children and communities in this state do not share in the success of our larger, more prosperous metros. And even in those places there are many of our neighbors who are economically insecure, who are a paycheck away from disaster, who have not had the same educational opportunities as some of us.

Since 1994, The Initiative has worked collaboratively with community development groups across the state to drive “innovation, investment, and action to create prosperous, sustainable communities.” The Initiative team works with a diverse group of public and private partners to leverage a broad array of assets to help communities thrive and families succeed.

As part of our work on the new website, we collected data on poverty and housing insecurity in this state, two areas where The Initiative is actively involved with its communities.

Some of the numbers you probably already know, like the fact that one in six adults and one in four children live in poverty in this state. Or that poverty for those without a high school diploma is significantly higher than for those with a bachelor’s degree—31 percent versus 4 percent.

But some of the data might come as a surprise.

In North Carolina, 8.4 percent of households are unbanked, meaning they don’t have either a checking or savings account. And 21 percent of the state’s households are considered underbanked, meaning that even though they may have a checking or savings account, at some point in the past year they have had to rely upon checking-cashing services, payday lenders, pawnshops, or refund anticipation loans to make ends meet.

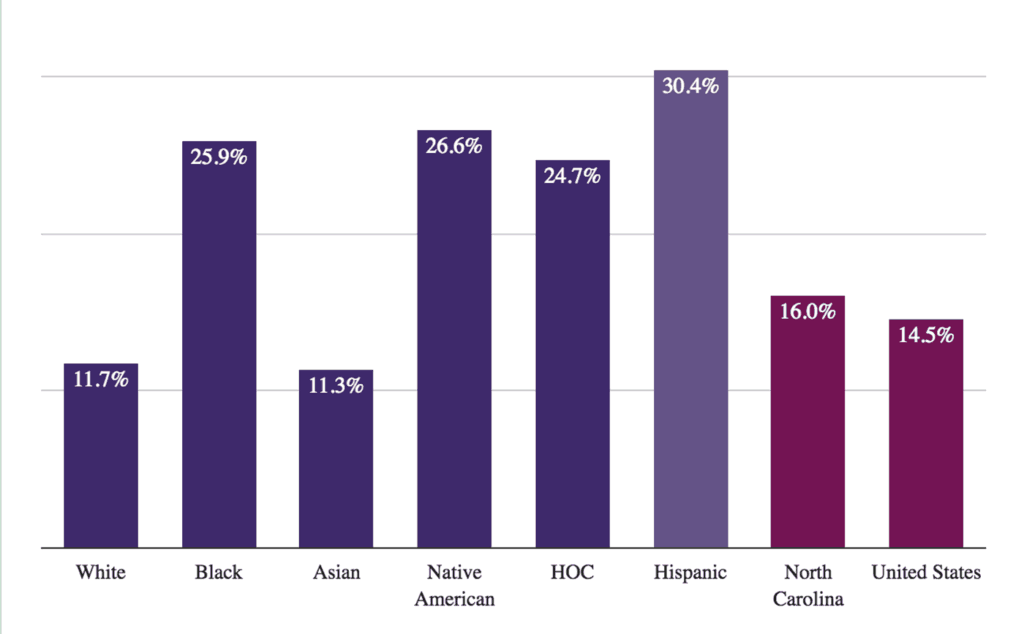

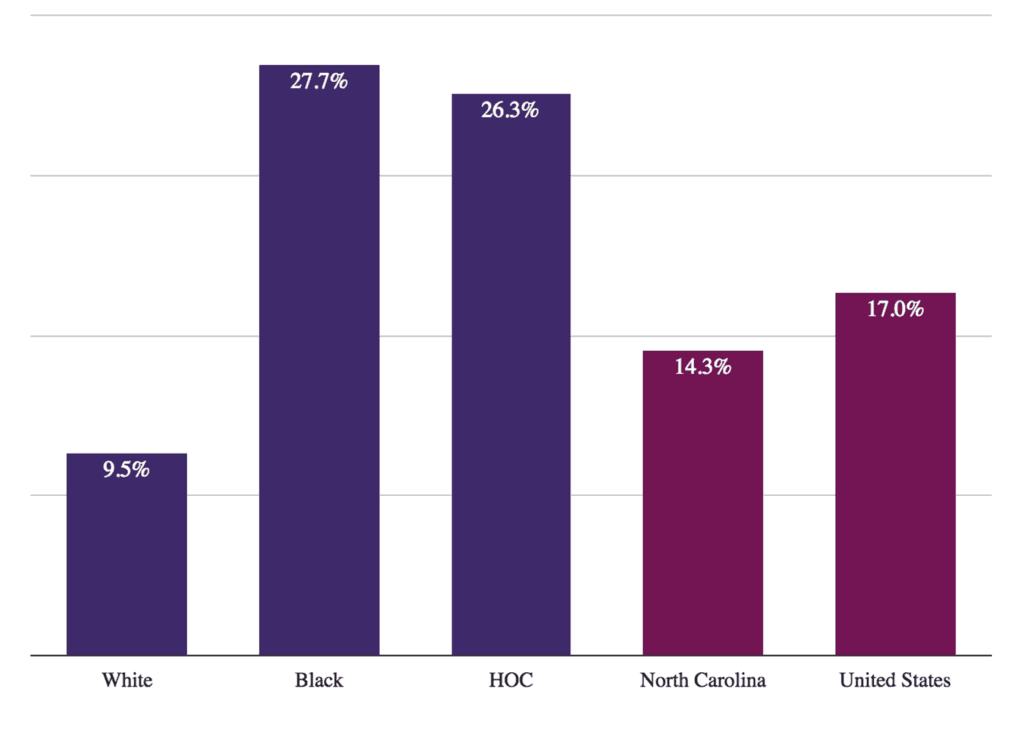

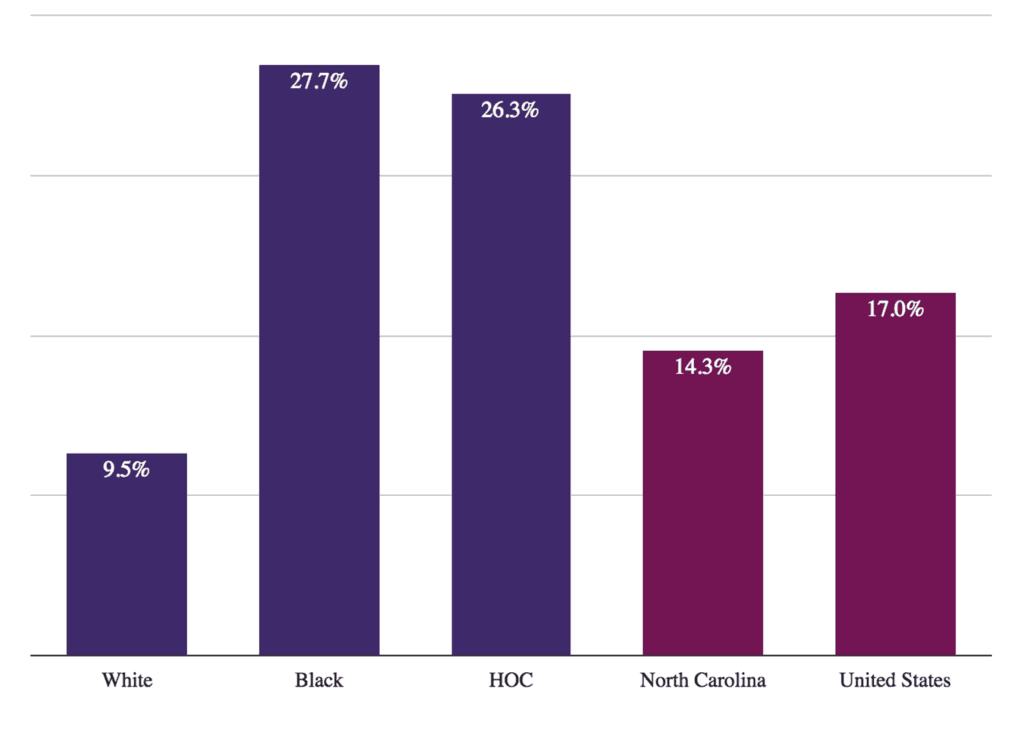

North Carolina’s income poverty rate, the percent of households with income below the federal poverty threshold, is 16 percent, compared to 14.5 percent nationally. But when disaggregated by race, African Americans and Hispanics have significantly higher income poverty rates than whites.

Income Poverty Rates by Race & Ethnicity, 2014

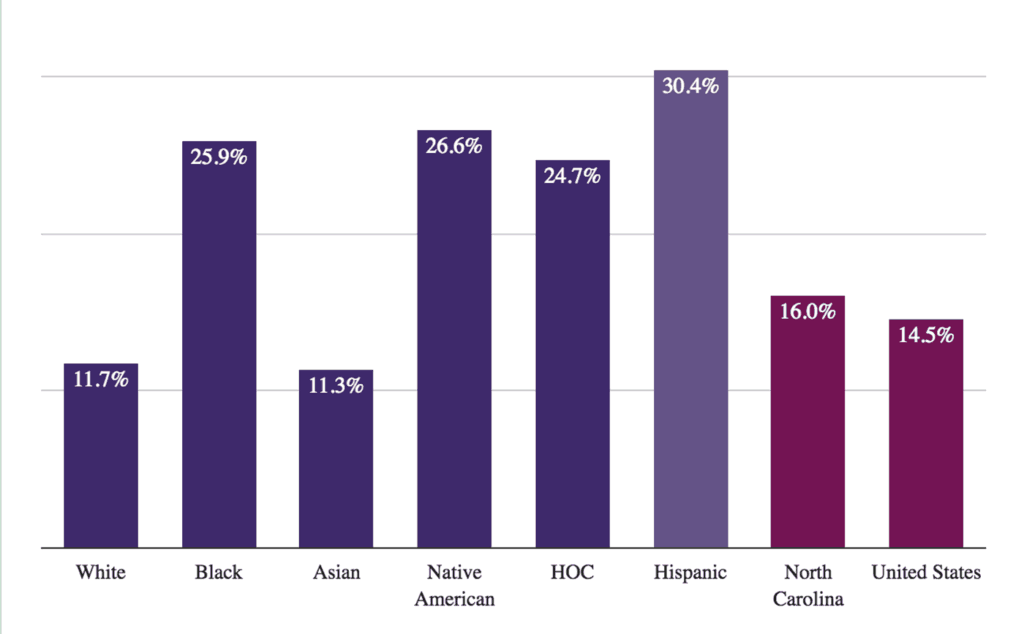

The numbers are equally disproportionate when examining extreme asset poverty, the percentage of households with zero or negative net worth—meaning a household owes more than it owns.

Extreme Asset Poverty, 2011

We also worked with The Initiative to gather housing data, a topic we have covered in detail before at EdNC as part of our Consider It Mapped series.

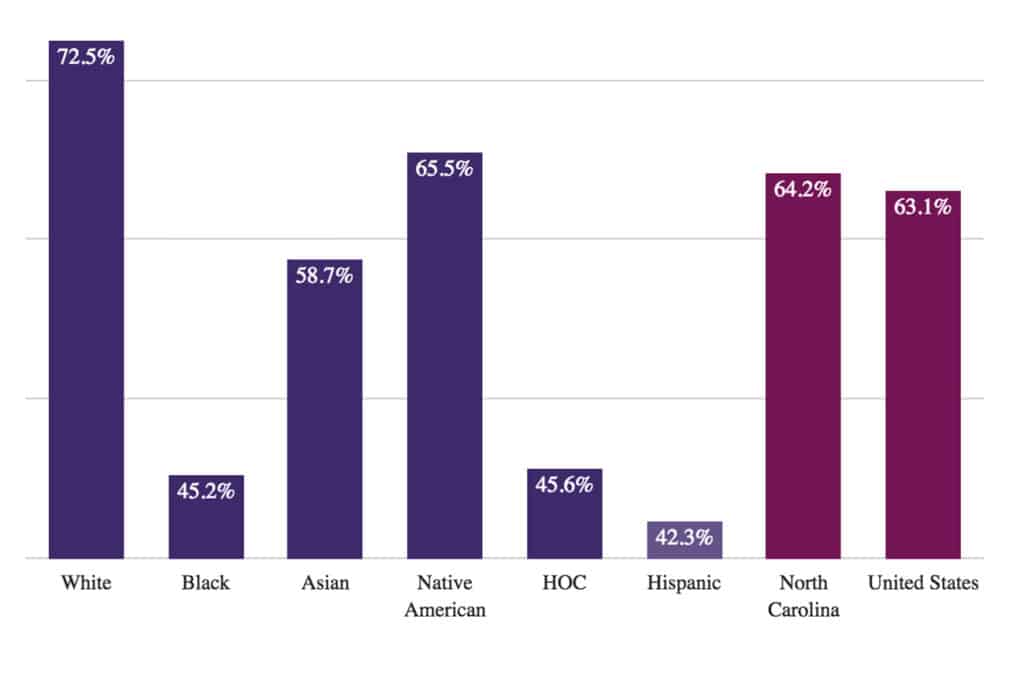

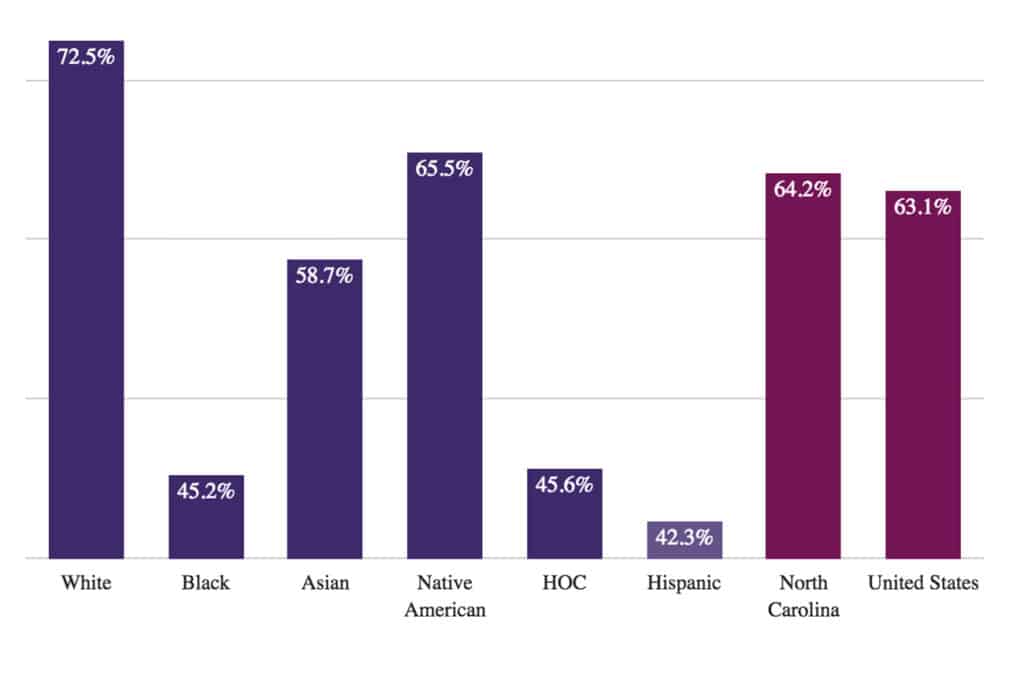

In 2015, a count on one night indicated there were 10,683 people homeless in North Carolina, 2,295 of whom were children. Homeownership in the state looks like the inverse of the poverty graphs above with significantly more white families owning homes than African-American and Hispanic families.

Homeownership

Compounding the issues of poverty and housing, is food insecurity. Ask any teacher how hard it is to teach a hungry child and you will hear first hand the effect of food insecurity in the classroom and on the ability of a student to learn.

According to Feeding America’s Mind the Meal Gap project, North Carolina had 1,764,800 people who were considered food insecure in 2014—564,240 of whom were children. Those numbers translate into more than 18 percent of the state’s adult population and more 26 percent of those under the age of 18.

Why does all this matter to the education policy discussion in this state?

Because those 7,735 hours when a student is not receiving instruction impact the 1,025 hours when they are receiving instruction.

Depending upon what is going on in that student’s life, sleep may be dependent upon where home is that particular night or be interrupted by episodes of domestic violence. Eating might not always be a certainty. Playing outside might not be an option in an unsafe neighborhood. Dreams might be pulled under by waves of persistent anxiety and stress.

That’s 7,735 hours that a teacher has no control over but which may burden a child in his or her classroom.

Last week, I joined The Initiative President and CEO Tara Kenchen on a trip to Bertie County to visit the Hive House, a one-stop food bank, community kitchen, job center, tech hub, after-school center, and a general all purpose sanctuary for at-risk children in the county. The Hive House, located in a late-19th Century home in Lewiston, is the brain child of local community leader Vivian Saunders. On the day we visited the house was dark and empty, closed due to an electrical fire in the walls that will require a complete rewiring if the structure is to be operational again.

Kenchen was joining a group of local leaders and representatives of state organizations to strategize a move to a larger facility, a move that is desperately needed to expand services to the area’s youth and young adults.

According to the Census Bureau’s American Fact Finder, Bertie County has a population of just over 20,000, with a racial breakdown of 62 percent African American and 36 percent white. The leading employer in the county is the local Perdue processing plant, which we were told employs nearly 2,000, or roughly 10 percent of the county’s overall population. (It is worth noting that the Perdue leadership has offered to pay for the entire cost of rewiring the original Hive house.)

Poverty is high in the county, with more than 25 percent of the total population and nearly 46 percent of children living below the poverty line. Educational attainment is low, with about 63 percent of the county having only a high school diploma or less.

Anecdotally, we heard stories from Ms. Saunders of an entire family of children being orphaned after the deaths of their young parents. We heard about the recent murders of three young men under the age of 25. We heard stories about substance abuse and joblessness.

But we also met leaders who were determined to improve their community, who were willing to dedicate the time and effort to the long fight of economic change in the place they call home.

It is in those places that the work of organizations like The Initiative is so important. Education and economic security can at times seem like a frustrating chicken-and-egg scenario until you realize that pressure must be placed along the entire spectrum of birth to adulthood to change a culture of a place, to change the life trajectory of a young person who might not believe there is anything more to their future than a low-paying job and another step in the cycle of intergenerational poverty.

That is why it is important we on the education side of the policy spectrum take the time to listen to those working in the economic and workforce development fields. That is why it is important for us to take a visit to a place like Bertie without ever stepping foot in a school building.

Change happens where there is sustained and persistent leveraging of resources and supports along the long arc of a child’s life. Because as we learned from our math teachers, there is big difference between 7,735 and 1,025.

Keep an eye out for The Initiative’s website, which will feature a data portal, similar to EdNC’s own Data Dashboard, allowing users dig deeper into the issues of hunger, poverty, and housing.