Editor’s note: In 2016 on Thursdays, EdNC’s Policy Points will examine through reporting, research, and reflection the points where politics, policy, and practice intersect. We will tell stories. We will examine data. We will speak to policymakers and practitioners. We like to think of it as real time policy analysis.

At the end of last year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS) released its annual “Rural America at a Glance” publication, a survey of economic, education, and demographic data for the nation’s rural communities. The Economic Research Service hosted a webinar yesterday with economist Lorin Kusmin, one of the co-authors of the agency’s Rural America at a Glance series.

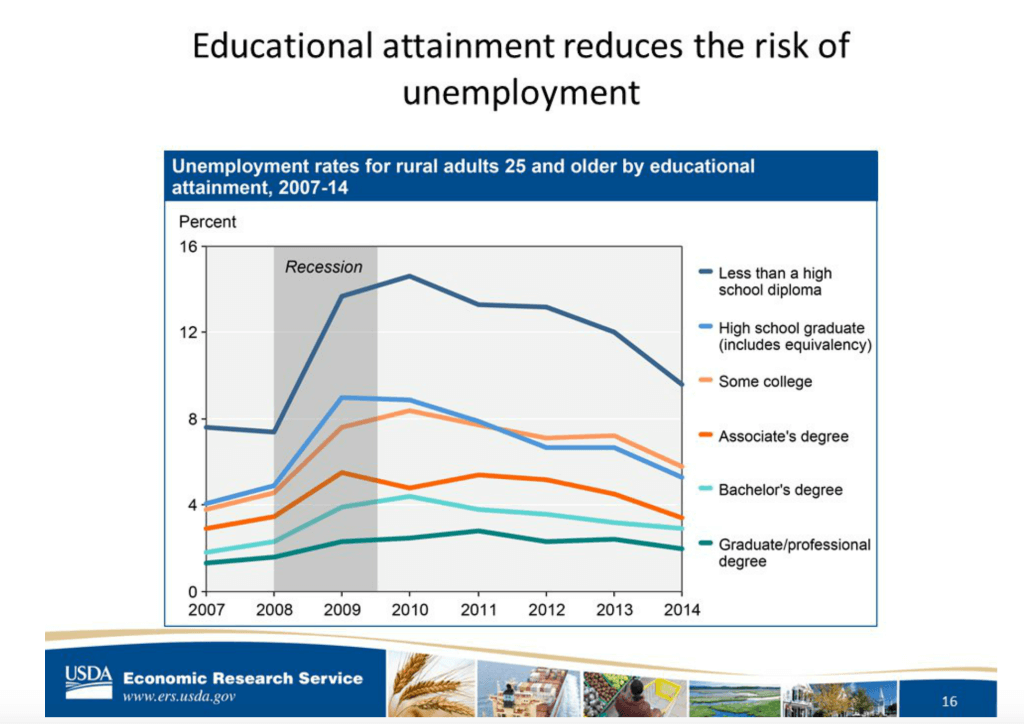

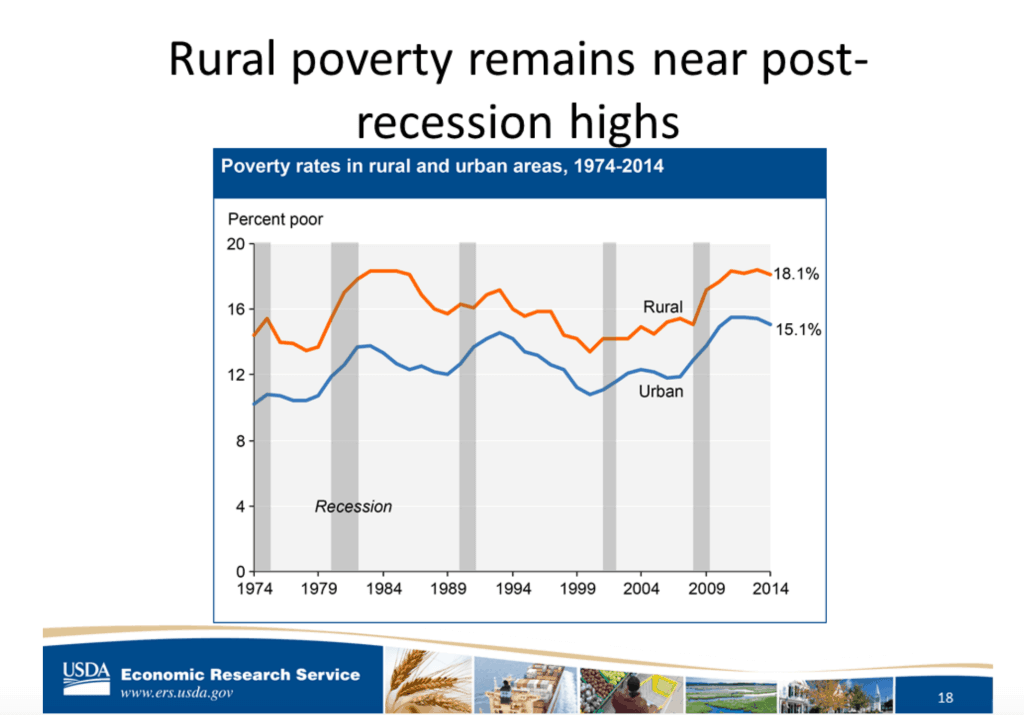

The good news is that educational attainment has increased in the nation’s rural places since 2000, with more residents having some postsecondary training or degree attainment along with a corresponding drop in the percentage of those without a high school diploma. And the unemployment rate has fallen in the post-recession recovery, though it is still higher than the unemployment rate for urban residents and remains above pre-recession levels.

Rural residents are still trying to play catch up to their urban counterparts when it comes to higher levels of educational attainment. Urban residents are still much more likely to have a bachelor’s degree or higher, but rural residents reporting some college or an associate’s degree has risen and represents a higher percentage of the rural population than the urban population.

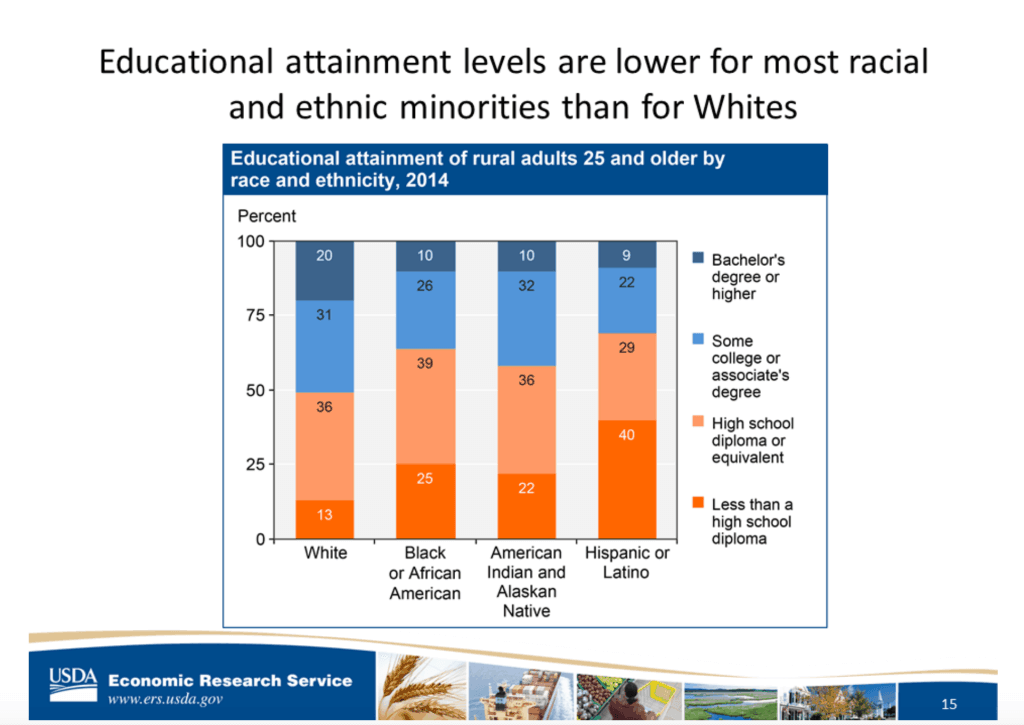

But in a post-recession workforce where the majority of new jobs being created will require at least some postsecondary education or training, many rural residents have not continued their education past high school. In 2014, 36 percent of rural residents had only a high school diploma, the highest percentage of the four educational attainment categories.

While neither the report nor Kusmin’s webinar touched on workforce projections, Georgetown’s Center on Education and Workforce projects job growth and the educational attainment needed to fill those future positions. A 2013 report from the Center projected that by 2020, 65 percent of all jobs will require some form of postsecondary education. That percentage has flipped from 1973 when 72 percent of jobs required only a high school diploma or less.

Simply put, gone are the days when a high school diploma could provide a ticket to a living-wage career, and with more than half of the nation’s rural residents holding only a high-school diploma or less in 2014, the future implications could be increased poverty and lower economic mobility.

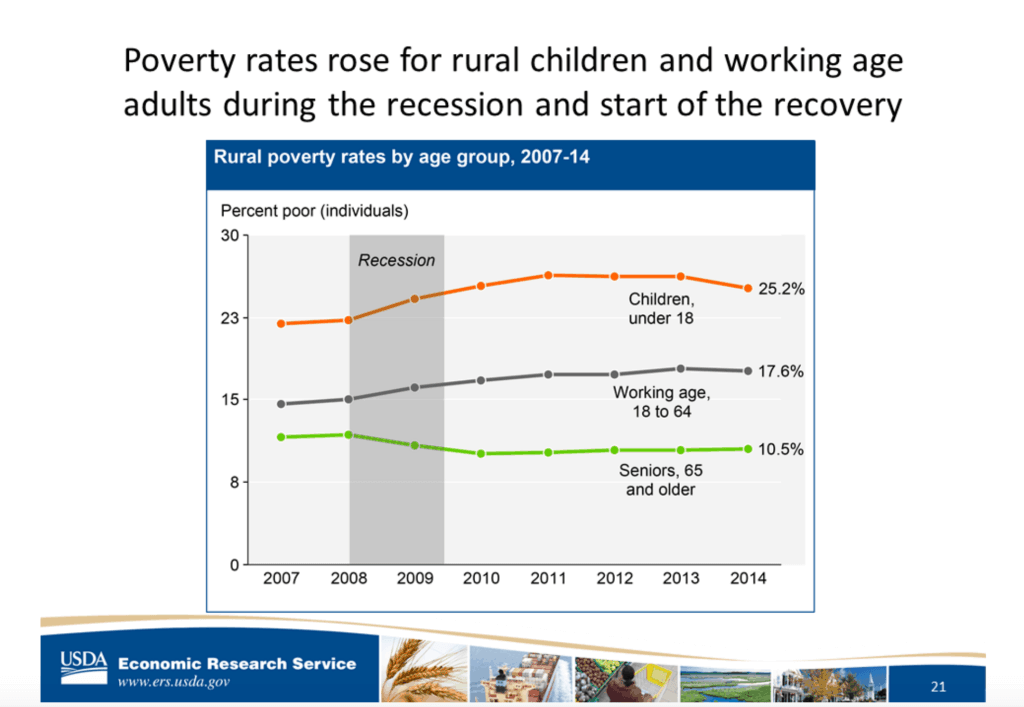

And more poverty is not something rural communities need. According to the ERS report, the rural poverty rate in 2014 was 18 percent, compared to 15 percent for urban residents. And it gets worse when those numbers are disaggregated by age, race, and educational attainment.

The poverty rate for rural children increased from 22 percent in 2007 to more than 25 percent in 2014. The report notes that children in rural areas are also more likely to be in “deep poverty,” as measured by being “in families with an income below half of the poverty level.”

In 2007, more than nine percent of rural children lived in deep poverty, compared to only six percent of the working-age population. By 2014, those numbers had increased to 11 and eight percent, respectively.

When disaggregated by race and age, the majority of rural African-American children live in poverty — more than 50 percent in 2014, an increase from 45 percent in 2007.

Childhood poverty was worse in rural counties with lower levels of educational attainment. The ERS report found that in rural counties with a high percentage (17 percent or higher) of adults without a high-school diploma, the child poverty rates was 32.4 percent, compared to over 16 percent in rural counties with a low percentage (eight percent or lower) of adults without a high-school diploma.

What does all this mean for North Carolina?

In his presentation, Kusmin said that there are roughly 46 million rural residents nationwide, representing 15 percent of the total population.

According to the ERS, North Carolina’s more than 2.2 million rural residents represented 22 percent of the state’s total population in 2014. That’s a decrease from 28 percent of the state’s total population in 1980.

Of those residents, an estimated 51 percent have a high school diploma or less, compared to 39 percent of urban residents in the state, and only 17 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to 30 percent of the state’s urban residents.

The good news for the state is there has been a sharp decrease in the percentage of rural residents with less than a high school diploma and an increase in the percentage of those with at least some college.

As noted in the ERS report, a parent’s educational attainment is an important indicator of a child’s educational success later in life.

The report notes that “Children of parents without a high school diploma are much more likely to be poor, since adults with limited education are more likely to be unemployed and to have lower earnings if employed than more highly educated adults.” Children born into poverty tend to have “less academic success and lower graduation rates.”

Low levels of educational attainment and childhood poverty are a concern for our state regardless of the zip code. Research has shown repeatedly that more education results in better health outcomes, more civic participation, and greater economic security.

But it’s also important to remember that the issues of poverty and educational attainment tend to be amplified in our rural communities, compounded by factors like higher unemployment, fewer living-wage jobs, and higher instances of chronic diseases.

Rural in North Carolina is not like rural in North Dakota. The majority of rural residents in this state are an hour’s drive from a metro area. And even though the state is becoming more metropolitan and more driven by an urban economic engine, there is an increasingly diverse rural population that will need to overcome unique barriers to academic success and postsecondary completion.

It’s good for all of us in this state, regardless of zip code.

The ERS webinar was recorded and will be available here within the next week.