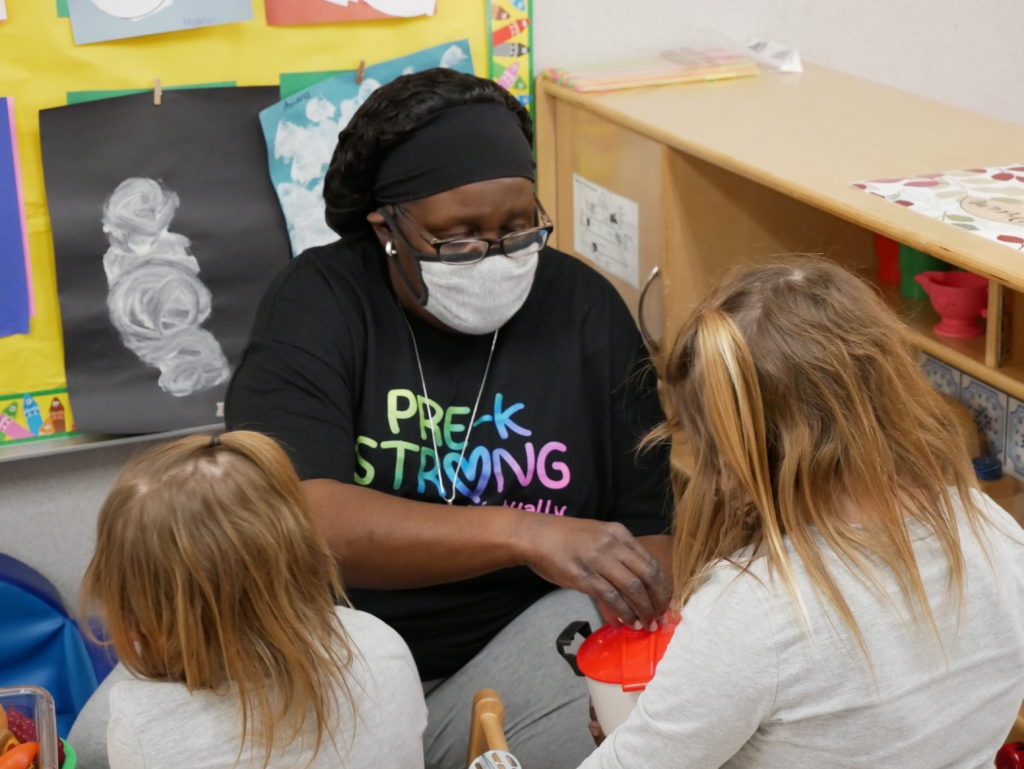

Tammy King has worked with children at Greene County Schools Pre-K Center for 29 years. Vanguler Morgan, a teacher assistant in the same classroom, has taught for 23.

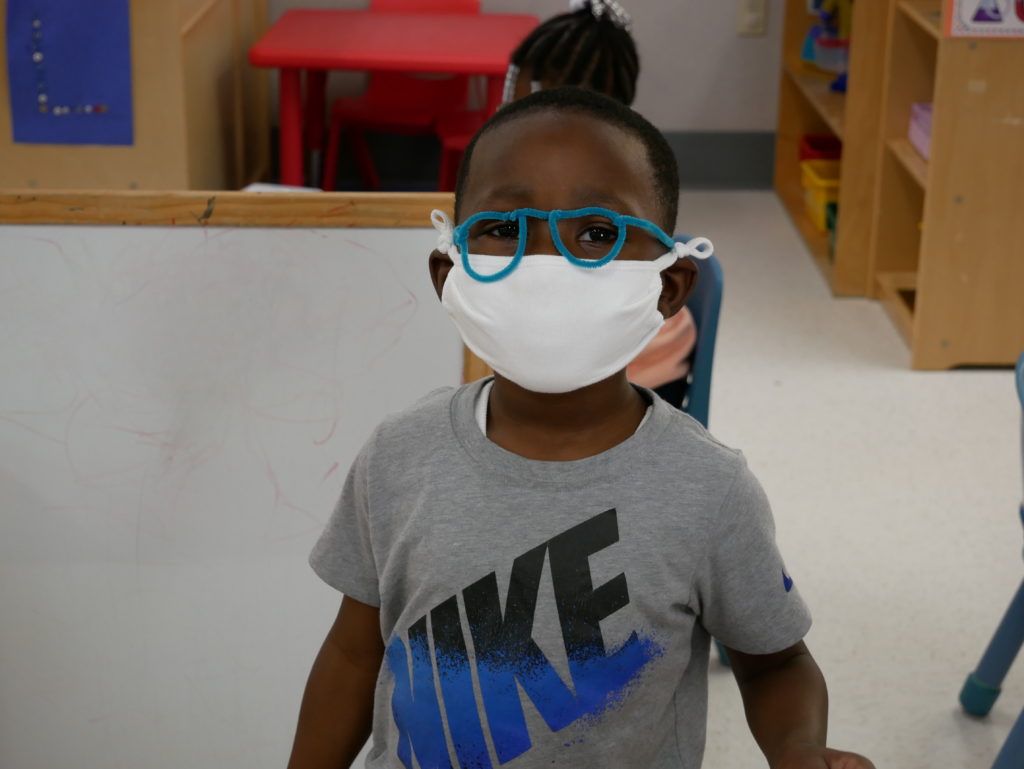

“They’re like sponges; they soak it all in,” King said as she twisted a pipe cleaner to make pretend eyeglasses for a student.

She said early education provides a solid foundation for school and beyond. “It’s not just academics, it’s social,” she said. “They learn how to share, how to have empathy. That’s something the world needs now more than anything.”

Greene County Schools Superintendent Patrick Miller said this kind of teacher experience is the heart of the district’s pre-K program, which has 10 classrooms that rely on multiple funding streams. NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds, is the largest funding source.

Yet a stagnant slot rate — the amount the state gives providers for each child — makes it difficult to maintain quality and invest in teachers, Miller said.

“The salaries of the teachers, of course, keep going up, which is a good thing. We want them to go up,” he said. “The teachers deserve those raises, but the slot rate hasn’t increased at all to help us keep up with those.”

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Miller explained that the state salary schedule factors in teacher experience for K-12 educators. Yet the funding for running the pre-K program is fixed. Since 2015, the state has provided $473 per child to public settings, regardless of teacher certifications. Different rates are provided to private settings depending on teacher education levels.

“You want to have veteran, experienced teachers, but they cost a whole lot more than the newer teachers,” Miller said. “But the slot rate generates the same amount of dollars regardless, so it creates complications.”

Julissa Lopez, preschool program coordinator at The Partnership for Children of Greene and Lenoir Counties, chimed in: “To say the least.”

The organization, which is part of the statewide network of Smart Start partnerships, provides supplemental funds to children covered by NC Pre-K since the state’s allotment does not cover the full need.

Yuvonka Davis, director of Greene County Schools Pre-K Center and the district’s principal of the year — for the second time around — said the limited funds affect more than just salaries.

“You start to look at your budget and go, what can I do without?” Davis said. “Well, really there’s not anything that you can do without, within that budget, because you need the funds not only to be able to cover the salary of your staff, but you need the funds to be able to provide sufficient resources, materials, instructional supplies for your students, and … to maintain any building facility.”

Tammy King, a teacher at Greene County Schools Pre-K Center, makes pretend glasses for student Ja’zari Peterson in her “three-school” classroom.

Ja’zari Peterson poses in his glasses and mask. All pre-K students in Greene County wear masks.

Vanguler Morgan, a teacher assistant, interacts with children during cehildren in the center’s only classroom for 3-year-olds.

Reaching the real need

Over recent years, the state legislature has allocated money to expand NC Pre-K — providing more slots at the same price. Yet many counties turned down the expansion funding.

A 2019 report from the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) studied why, and found multiple barriers to expansion across different kinds of settings — including transportation, space issues, rising operational costs, and the stagnant reimbursement rate. The report estimated that the reimbursement rate covers 61% of the cost of providing education for one child.

In 2019, the General Assembly passed a law setting a goal to reach 75% of eligible children in each county and requiring the Department of Health and Human Services to further study why some NC Pre-K sites can’t expand and why other early education providers don’t offer the program at all.

The Frank Porter Graham Institute at UNC-Chapel Hill released that study in February 2020, and again found too-low reimbursement rates as one common challenge.

Greene County was one of many counties that has declined expansion funds in recent years. Miller and Davis said that was because they felt the center needed more funds to sustain its current program first.

“Ideally, I’d like there to be universal pre-K, but the first thing that has to happen is we need a slot rate increase for the slots we have, and then we can start to talk about expansion,” Miller said.

Lauren Vines, a pre-K student in Greene County, works with Legos.

NC Pre-K lead teacher LaVania Edwards shows a picture during carpet time to her four-year-old students.

The need is there, Miller, Davis, and Lopez said. Most years, there is a waiting list. But that need is hard to put a number on, as the district is only aware of families who apply. The NIEER report estimated that in 2017, Greene County was not reaching 52-75% of eligible 4-year-olds.

There are two empty classrooms at Greene County’s Pre-K Center, one of which has already been inspected and passed the standards to house NC Pre-K students.

“Maybe before I retire, we’ll have that classroom filled up — but ultimately I’d like to see universal pre-K for those that want it,” Miller said.

Inside the center

Walk down the hall from the two empty classrooms, and you’ll find the pre-K center’s oldest students. The district’s family literacy program supports adults going back to school to further their education — often parents of children attending pre-K — through a partnership with Lenoir Community College.

Program participants are often English language learners, like Jada Sifuentas, whose 5-year-old is in pre-K. Sifuentas said she is thankful for the program — she’s understanding more and more English these days. She was a nurse in Mexico, and hopes to continue her education to become one again, she said.

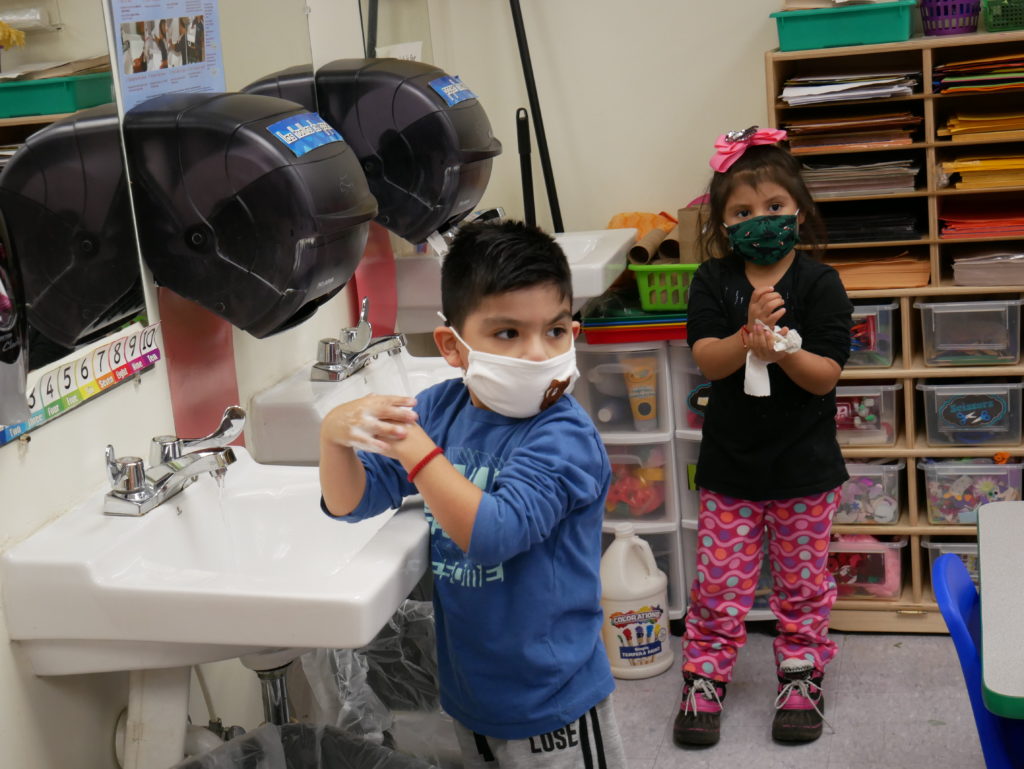

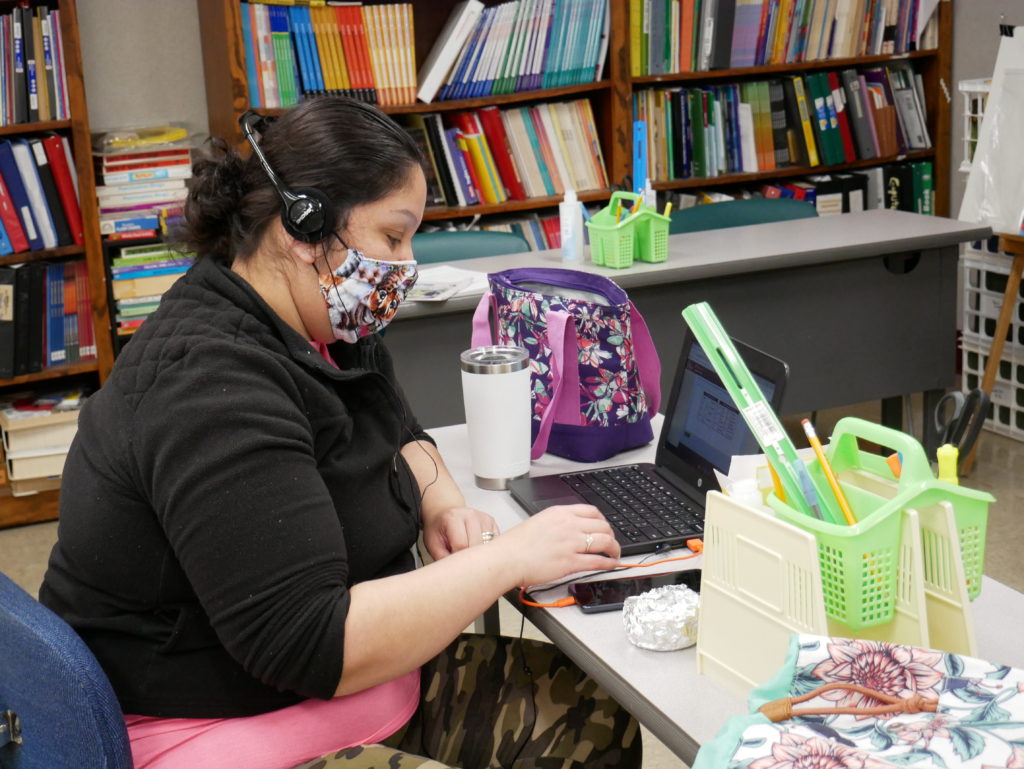

In the main building across the playground, eight pre-K classrooms serve 4-year-olds, including a standalone Exceptional Children’s class, and this year, a classroom with only a teacher and her laptop, providing remote instruction. Along with the district’s elementary schools, pre-K students are operating in plan B, a hybrid model of remote and in-person learning. All teachers and students wear masks — a decision Davis, the center director, made. State guidance requires masks only for children 5 years old and above.

She said partnerships with local child care providers have been important throughout the pandemic, as many children engage with remote instruction from a center.

“We’re looking forward to the day when everybody can return back in a safe manner,” Davis said. “… We’re in school, and we’re just being very creative on how we’re delivering appropriate instruction for young children, for all children.”

Crystal Godinez-Ramos and Da’Kari Bynum grab books during a class transition.

Stacy Roberson, a Greene County pre-K teacher, signals for a remote student to unmute.

Matthew Osorio-Najera and Crystal Godinez-Ramos sing a song while washing their hands.

In trailers outside, you’ll find the center’s “three-school,” a class exclusively for 3-year-olds from low-income families. These students are funded through the Smart Start partnership. King has been teaching in this classroom for the last four years.

“It’s just one class in this whole county for 3-year-olds,” King said. “We have a waiting list every year. There’s definitely a need. More funding, more classrooms.”

Lopez, who works at the partnership, said she hopes the center can continue to step back in age.

“We knew if we got the children another year, they would benefit so much more by having two years of pre-K, so imagine five years of pre-K, with a quality teacher and a quality environment,” she said.

The partnership doesn’t just support pre-K, but works to strengthen the quality of early care and education across settings, including providing technical assistance to private centers, none of which receive NC Pre-K funds in Greene County. Lopez said more Smart Start funding, which also comes from the state, would help lift the entire system starting at birth — from literacy programs like Reach out and Read to home visiting programs like Parents as Teachers.

“We look at the community’s needs,” Lopez said.

Editor’s note: Patrick Miller serves on EducationNC’s Board of Directors.

Recommended reading