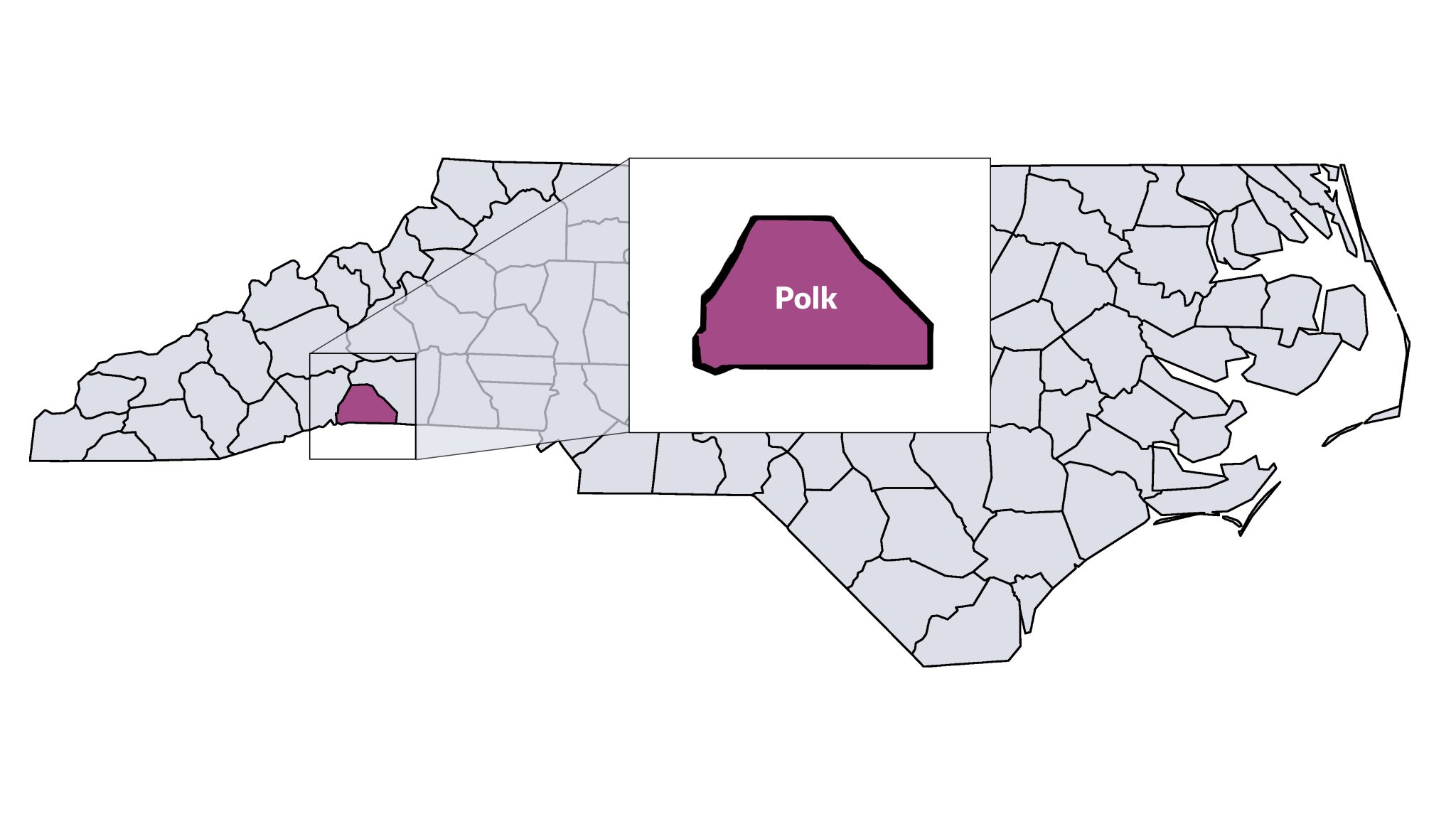

Research tells us that high-quality preschool makes an important difference for children later in school and in life. In Polk County, Superintendent Aaron Greene says the public school district’s pre-K program, which reaches 75-85% of 4-year-olds annually, means school readiness for incoming kindergartners, stronger relationships with families, and academic success later.

Since a 1995 donation from a local philanthropist kicked off the district’s preschool efforts, Polk County Schools has created a new community expectation, Greene and other district leaders said.

“Instead of it being time for kindergarten enrollment, it’s talked about (as) it’s time to get your kid into pre-K,” Greene said. “So we’ve shifted that process down.”

Yet pre-K access is only part of the picture. How preschool fits into students’ larger journeys matters to Polk County leaders and educators. Experts say the experiences students have as they transition from pre-K to elementary school can have big impacts on their learning — and on the gains they made in preschool.

“When we talk about pre-K being another grade in our schools, that can’t just be for parents and families; that has to be for our entire organization,” Greene said.

Watch below as Polk County leaders and teachers talk about their districtwide understanding and respect of early childhood education.

Meaningful transitions

Michael Little, an assistant professor of educational evaluation and policy analysis at N.C. State University, studies the transition from pre-K to kindergarten. A 2020 Early Learning Network report, which Little co-authored, found misaligned standards, curricula, and assessments between pre-K and elementary environments in North Carolina.

“We all know that early childhood is a very sensitive period for brain development and just setting the foundation for later success, and one of the keys to healthy development is sustained, healthy, rich relationships and stimulating environments,” Little said. “Often the transition from pre-K to kindergarten is a very abrupt transition where the two worlds are often not aligned — with pre-K having a much more developmental focus, being play-based, and centered on the child — moving into an increasingly academically-focused kindergarten context, where there’s a lot more whole-classroom instruction and focus on early academic skills. And that transition is extremely difficult for all kids, but it’s particularly challenging, the research tells us, for students from under-represented backgrounds, students of color, and students from lower socioeconomic status groups.”

In Polk County, teachers say that transition has become seamless. Pre-K classrooms are often down the hall from kindergarten. Students in pre-K visit kindergarten classes throughout the year. Pre-K and kindergarten teachers have frequent discussions about students’ academic and developmental progress, what teacher or class might be the best fit, and what kindergarten and pre-K standards look like. Pre-K teachers and district personnel make home visits (when there’s no pandemic) and help parents set and meet goals for their children and families — forming relationships that last throughout the children’s educational career.

Kathy Harding, the district’s health and pre-K director, has seen the evolution of the district’s program since the early 2000s. “We’re very, very much aware that those are two worlds that aren’t the same, and it’s up to us to make it so that we can live happily together so that we are one,” Harding said. “That does not happen overnight.”

“It’s up to us to make it so that we can live happily together so that we are one.”

Leadership

Ronette Dill, who has worked as a teacher and principal in Polk County and is now the district’s director of curriculum and instruction, recalls talking with principals from other districts about pre-K a few years ago.

“We never see them, we never talk to them, but we know they’re there,” Dill said of principals’ comments. “That always just hurt my heart to think that was going on across North Carolina, when I knew the success we were having in Polk County with making pre-K a part of the school.”

Polk County pre-K teachers pointed to school and district leadership as critical to their success. Laura Jane Howald, pre-K teacher at Polk Central Elementary and the district’s teacher of the year, said she has worked in districts with leaders who did not support or understand pre-K.

“Sometimes I think of that analogy that if they’re at the head and we’re at the body making things happen, if the head isn’t functioning or not supportive of what the body is doing, things are all over the place,” Howald said. “Our superintendent is so supportive … it makes all the difference in world.”

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

The court-ordered WestEd report, a 2019 study of North Carolina’s education landscape in the ongoing Leandro court case, recommends professional development on early childhood education for principals, who often come from middle or high school environments.

That was the case for Greene, a former high school math teacher and principal.

“It’s a big change,” Greene said. “Because we’re used to algorithms. We’re used to procedures — here’s your lesson plan, you do independent practice, you do guided practice. So shifting from that K-12 kind of mentality to pre-K and truly working to understand what that means developmentally for kids is significant. And if your leaders in your district aren’t doing that, then they’re not going to have a good idea of how to support those individuals.”

For Greene, that meant learning about the underpinning philosophies and approaches of early childhood educators.

Jessie Roush, pre-K teacher at Tryon Elementary School, talks with a student during center time. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Heather Elliott, an assistant pre-K teacher at Tryon Elementary School, assists student Dorian Crespo-Torrales while creating paper snowflakes. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Preparing children for school, for life

Polk County’s pre-K classrooms, like many early childhood classrooms across the state, are rooted in play. Most of a student’s day is spent in centers like arts and crafts, science, house, or blocks.

Teachers use the HighScope Preschool Curriculum. The HighScope Educational Research Foundation was founded by David Weikart, a researcher who led the Perry Preschool Project back in the 1960s, a well-known longitudinal study on the impacts of early childhood education on 123 Black children from Michigan throughout their lives. The results when the students were 40 years old showed that they were more likely to have graduated from high school, hold jobs, and have higher earnings than individuals who did not attend preschool.

The curriculum shapes the days of Polk County’s preschoolers. Activities are structured through a “plan, do, review” sequence. Children share what their plans are, execute that plan, then reflect with their peers on their experiences.

Teachers regularly are asking questions to build critical thinking skills. They are beginning children’s process of learning to read. They are also problem-solving alongside children. They are helping students acknowledge and express their emotions.

In the morning meeting at Saluda Elementary, Ashley Marion asked students to turn to each other with thumbs-ups and thank their classmates for being there. At Sunny View Elementary School, Shelley Upton asked children how they could tell what feelings children were expressing on a set of cards. At Tryon Elementary, Jessica McEntyre had children assist one another in a lesson on letters.

Teachers use Second Step, a separate curriculum focused on social and emotional learning that has weekly themes such as empathy and emotion management.

“At the core of what I do as an educator — if folks ask me what I would like for a child to learn being in my classroom — I want to make sure they are socially/emotionally competent or prepared for not only what they’re going to be doing in school but also what they’ll be doing in life,” Howald said.

“If they love coming to preschool, their first experience, they’re going to like going to the big school.”

These social and emotional skills, coupled with wraparound services for families, make a larger impact than academic preparedness.

Amanda VanDuyne, the district’s family services specialist, said she’s seen the early focus on attendance carry throughout children’s school careers.

So do the relationships that she and other district personnel form in preschool, when they help parents “become advocates for their children and for their families.” That could mean anything from helping parents find jobs or go back to school, to referring children and families to medical or dental services, to arranging parent input events.

McEntyre puts the long-term impact on children this way:

“If they love coming to preschool, their first experience, they’re going to like going to the big school.”

Shelley Upton, pre-K teacher at Sunny View Elementary School, ties a student’s shoe during a lesson on emotions. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Brantley Carter, a pre-K student at Sunny View Elementary School, decorates a miniature Christmas tree. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Understanding and respect between pre-K and elementary school teachers is also encouraged through vertical teams. Pre-K teachers meet with kindergarten and first-grade teachers to discuss their teaching strategies and, when it’s time for students to transition, specific students’ needs.

Understanding these principles, Greene said, helps him explain to parents, teachers, and leaders why and how pre-K works.

“Absolutely a necessary component if you’re going to go down this road is to have those conversations, to get people to buy in and be on the same page with: this will benefit us in the long run if we let them do their thing and not put pressure on them. ‘Hey, that kid doesn’t know his ABCs yet.’ We’ll get there,” Greene said. “It’s more important right now that they understand how to do school, that they understand how to get along with other people, that they can feel comfortable in their own skin.”

Harding said maintaining a culture that values early educational philosophies has been “a work in progress” over the years. Educating teachers who are new to the system is still needed — whether it’s an elementary teacher who sees preschool as babysitting or a pre-K teacher who has upper-grade experience and is too academic-focused.

“If a new place is looking to add preschool to their school system, there is a learning curve and a transition,” she said. “You have to build those good … relationships.”

Unique history, unique monopoly

An investment from local philanthropist Margaret Forbes began the district’s path to serving pre-K students more than two decades ago. Forbes bought an old Duke Power building next to Tryon Elementary School in 1995 and donated it to the school system, under one condition: that it be used to serve young children.

“The word got out,” Greene said. With more support from Forbes, every elementary school had at least one pre-K classroom by 2000.

The Forbes Preschool Education Center is still in operation today, and each of the four elementary schools offer preschool, serving 75-85% of 4-year-olds annually and providing comprehensive services to children no matter the funding stream used to pay for that child. Some 3-year-olds who are eligible for Head Start or the Preschool Exceptional Children’s Program also attend.

Sayuri Ramírez, a pre-K student at Tryon Elementary School, poses during center time. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Averlee Painter, Emrie Fulmer, pre-K students at Sunny View Elementary School, search for decorations during arts and crafts. Liz Bell/EducationNC

The district is the NC Pre-K contractor and the Head Start grantee. It is also the only formal early education provider in the county. In North Carolina, there are at least six early education programs and funding streams that public and private settings use to provide care and education to preschool children.

Depending on where you go in the state, different entities administer those funds. In the case of NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds, funds are administered by the public school districts in more than 40 other counties. In other places, the state contracts with either the local Smart Start partnership or a Head Start agency.

Polk County is one of 14 public school districts that are Head Start grantees.

Harding said the district, which spends about $1.25 million a year on pre-K, uses NC Pre-K and Head Start as its primary sources of funding, along with Title 1 funds, an Exceptional Children grant, a local county commissioner allotment, and parent fees. Some parents — 11 of 100 this year — pay $400 a month.

Harding says streams are combined to serve children and create equal experiences despite differences on the back end as far as requirements and standards. This is possible, she said, because of the control the district has over these funds.

Greene said he hopes other districts with varying early education landscapes will partner with the agencies and providers in their counties to support children.

“At the end of the day, we want to make sure that every child enters our schools prepared to be successful, and to do that we all have to be on the same page, or at least communicating about what’s going on,” he said.

Harding and Greene said there is a particular need for infant and toddler care for working parents in the area. Besides a nearby Western Carolina Community Action program that provides Early Head Start for some eligible children, there are no options. Though there are no concrete plans yet, Greene and other district leaders said they would love to help fill that need or partner with other organizations to do so.

“If you could get in those doors, again, you’re handling things upstream, and you’re going to solve a lot of the problems downstream,” Greene said.

Recommended reading