As the government shutdown enters its second month, families that receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits are missing full payments, and others are experiencing temporary Head Start program closures.

During disruptions to food access and federal funding, child care programs are adapting to meet families’ needs — while being concerned for their own stability.

“We are trying to be a bridge,” said Kimberly Shaw, owner of A Safe Place Child Enrichment Center, a child care program in Raleigh with three locations that emphasize nutrition, exercise, and nature-based learning.

Shaw’s program is part of a statewide project, Farm to Early Care and Education (ECE), which is built around the idea that child care programs can act as links between families and healthy food, while teaching both children and families about the importance of nutrition throughout life.

![]() Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

The effort is housed at the Center for Environmental Farming Systems, a partnership between NC State University, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, and the state Department of Agriculture.

Funding, training, and awareness are needed to help programs reach children with high-quality food at a crucial period of learning and development, said Shironda Brown, interim director of Farm to ECE.

Since 2016, the effort has provided early childhood educators and local support personnel in 29 counties with professional development. The statewide team’s sole funding source is the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), but local Smart Start partnerships and NC State Extension agents also work on the ground to support providers in their efforts.

A planned extension of the USDA’s Local Food for Schools Cooperative Agreement Program would have provided funding for fresh fruits and vegetables at child care programs serving low-income families for the first time. But the program was canceled in March 2025 under the Trump administration.

The Farm to ECE effort is seeking grant funding, Brown said, with a goal to reach all 100 counties with training on gardening, cooking with and for children, local food procurement, and community engagement. This would not only bolster the health of children and their families, Brown said, but of local food systems — especially in rural parts of the state.

Why to start

At Shaw’s program in Raleigh, a coffee bar greets parents during drop-off with coffee and creamer — as well as grab-and-go apples and bananas.

“We’re trying to feed people, because I made a connection: If the children are hungry, the parents are too,” Shaw said.

For the last 20 years, Shaw has led her staff on a journey to incorporate fresh, local food into the fabric of her program.

It all starts with a belief, Shaw said, that providers can play an important role in the health of children and families. Her own background sparked a desire to want better health outcomes for other children.

“I always knew that because of my childhood and our limitations, that I had the ability to at least make a difference in the lives of children. We have them about 10 hours a day — that would be a huge way to make an impact,” Shaw said.

The earlier healthy food is introduced, the better. Experts say that early childhood nutrition is linked to healthy brain development and that exposure to a variety of foods can lead to important lifestyle patterns.

From 2022 to 2023, about a third of North Carolina children under 5 years old did not eat fruits daily, almost half of young children did not eat vegetables daily, and 60% of young children had a sugary drink at least once a week, according to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2025 Early Childhood Nutrition Report.

Better habits and new policies are needed, Brown said, pointing to increasing health issues in children in recent decades.

“If we don’t get together and change that trajectory, what truly is going to happen?” she said.

Early childhood providers have a large opportunity, Shaw said.

“We know that the beginning of any good day starts with nutrition and a well body,” she said. “That is through food and exercise — that’s for all of us. If we start shaping children palettes in the womb and then at their first initial contact, that’s a huge beginning.”

Where to start

Shaw said her first step in implementing Farm to ECE was reaching out to her local Smart Start partnership, Wake County Smart Start, which helped her connect with people and resources. That is still her biggest piece of advice: Start small, and reach out to local partners.

Her own efforts started with planting tomatoes in bales of hay and a few vegetables in containers. Then she started buying fresh produce from the farmers market. As her program grew in size, she connected with a local farmer through the partnership who would deliver produce directly to classrooms.

“(The children) would do the first wash of the produce,” Shaw said. “We turned our water tables into places where you can wash collards. The next day, they’re eating those same collards that they washed the day before. So a huge connection between the growth of it, the prep of it, and they might even do the chopping.”

Providers should also reach out to their local NC Cooperative Extension center for help connecting with local food sources, said Tamiko McCullough, the healthy initiative coordinator at Wake County Smart Start.

NC Cooperative Extension is a partnership between the state’s two land-grant institutions, NC State and North Carolina A&T, and has 101 local centers with more than a thousand experts on agriculture, health, nutrition, and other local issues.

McCullough is operating a pilot program, funded by Wake County, with several local child care centers and family child care homes in partnership with a local Extension agent and Farmer Foodshare, a food hub based in Durham that delivers fresh produce to participating programs.

McCullough also hosts virtual cooking classes, farmers markets, and works with programs to start gardens and build outdoor learning environments. She said providers who might feel overwhelmed can look for interest in a teacher, parent, or volunteer.

“An ally or cheerleader or hand-holder — I think that also makes a very big difference,” she said.

The Farm to ECE website has a variety of resources for both local support personnel like McCullough and child care owners, directors, and teachers on food purchasing, integrating nutrition into common early childhood curriculum, and how to cook with and for young children. The state Department of Health and Human Services website has tools for incorporating and getting reimbursed for local foods for participants of the Child and Adult Care Food Program, a federal program that helps child care providers pay for healthy food for eligible children.

Brown said child care providers should know that “it’s not extra work,” and “they can implement everything with what they’re already doing.”

Related reads

On top of professional development events with providers from multiple counties, Brown also runs trainings for individual programs.

Leveraging staff members’ natural interests and skills can also help programs get started, she said.

“They can piggyback off each other,” Brown said. “If one person is not good at gardening, don’t go out there and garden with the children. Get someone else to take your children out and garden, because maybe you’re good at writing, and your contribution within this whole center is writing up what everybody did. So there’s a place for everybody.”

Brown, McCullough, and Shaw all said they’ve seen transformation in staff, children, and parents who are initially skeptical to new foods and practices.

Brown said she often walks into rooms with “walls up” and leaves with educators making connections between their own health and the health of the children and families they serve.

“This is about you at home too,” Brown said she often tells teachers. “This is not that just about the children you serve. It is about the whole community — the children you serve, their parents, your household, you as a whole. When that wall comes down, there’s no greater feeling.”

‘Eternal revolving doors’

Broader investment is needed to improve the quality of early learning environments — including the food children access, experts told EdNC.

At Shaw’s program, that means consistent funding in order to recruit and retain teachers, purchase materials, and maintain outdoor learning environments.

“You invest, and you train them … and if they leave, hopefully they go somewhere else and spread the good news — but then you have to do that again,” Shaw said.

Pandemic funding from the federal and state government ran out in March. Providers and advocates are asking the legislature for $145 million to help programs serving low-income families receive more funding per child. More than 500 program directors and owners signed a letter sent to policymakers in October. Programs need funding, the letter said, to draw in teachers with competitive wages.

Related reads

Some advocates are pointing to the Child Care WAGE$ program as a lower cost option for stabilizing the field. Operated out of the nonprofit Early Years, the program provides education-based wage supplements to early childhood teachers. The turnover rate in 2025 for participants was 13%, according to Early Years, compared to a statewide rate of 38%.

“Pay my early care and education teachers what they’re worth for taking care and nourishing the most vulnerable lives that are on this earth,” Brown said. “We’re trying to save their lives for the future, and we can’t do that when we have eternal revolving doors at these child care centers.”

Getting outside

For many child care programs across the state, emphasizing nutrition goes hand in hand with creating opportunities for children to learn outside.

Shaw’s program was an early partner of the Natural Learning Initiative (NLI), established in 2000 by NC State’s College of Design, which promotes “the importance of the natural environment in the daily experience of all children, through environmental design, action research, education, and dissemination of information.”

NLI’s website summarizes a decade of research that has linked natural learning with stress reduction, improved academic performance, increased creativity and problem-solving, and improved nutrition.

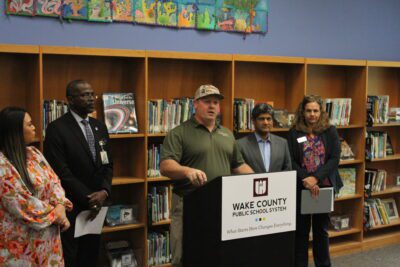

On EdNC’s recent visit to Shaw’s program, children and staff gathered outside under a gazebo and counted down to 10:00 a.m. to bite into local produce and celebrate NC Crunch Day, an annual celebration of healthy foods in child care centers and K-12 schools.

Then they dispersed to play in outdoor learning centers, run on the track, and ride tricycles. Shaw said on some days, one of her educators teaches children how to climb trees. Rain is just a chance for puddle splashing.

Byron McIntyre, program support manager at Shaw’s program, pointed out sensory gardens, a nearby chicken coop for field trips, and an outdoor infant classroom. He said children learn, eat lunch, nap, and grow and harvest food outside.

He sees the impact daily, especially during stressful times.

“That ability to connect with nature,” he said, “getting that fresh air — it just changes their whole day.”

Recommended reading