|

|

Serious policy proposals are being considered by North Carolina’s legislature. President Pro Tem Sen. Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, is calling it the “largest expansion of school choice” since the state started the Opportunity Scholarship program 10 years ago.

And those proposals are engendering an appropriately serious reaction. In May, Gov. Roy Cooper declared a state of emergency for public education.

Whether you identify as unaffiliated, Democrat, or Republican — and there are 2.6 million, 2.4 million, and 2.2 million of you, respectively, who are registered to vote — this statewide conversation about the future of our public schools deserves your attention.

Rural Republicans in Texas derailed similar policy proposals. “GOP members from rural areas have consistently proven hostile to programs they believe would unsettle the finances of local school districts, which are often the biggest employers and social anchors in their communities,” reports The 74.

Here is what you need to know.

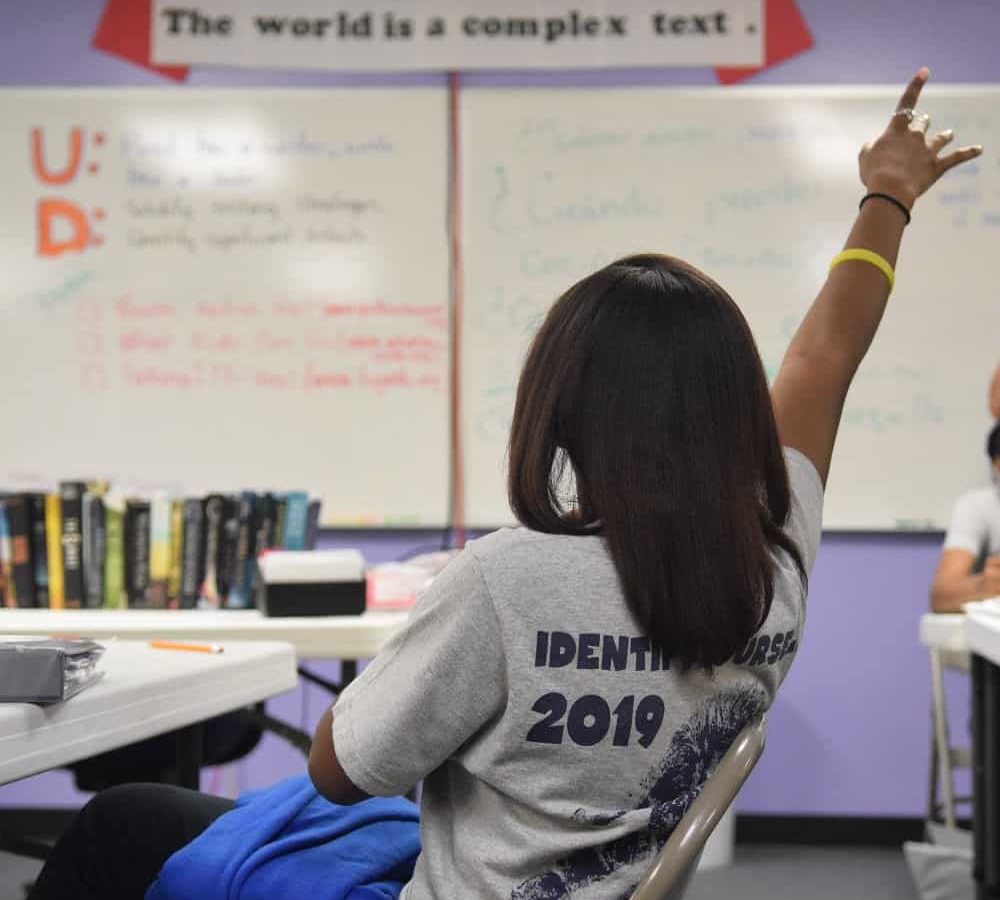

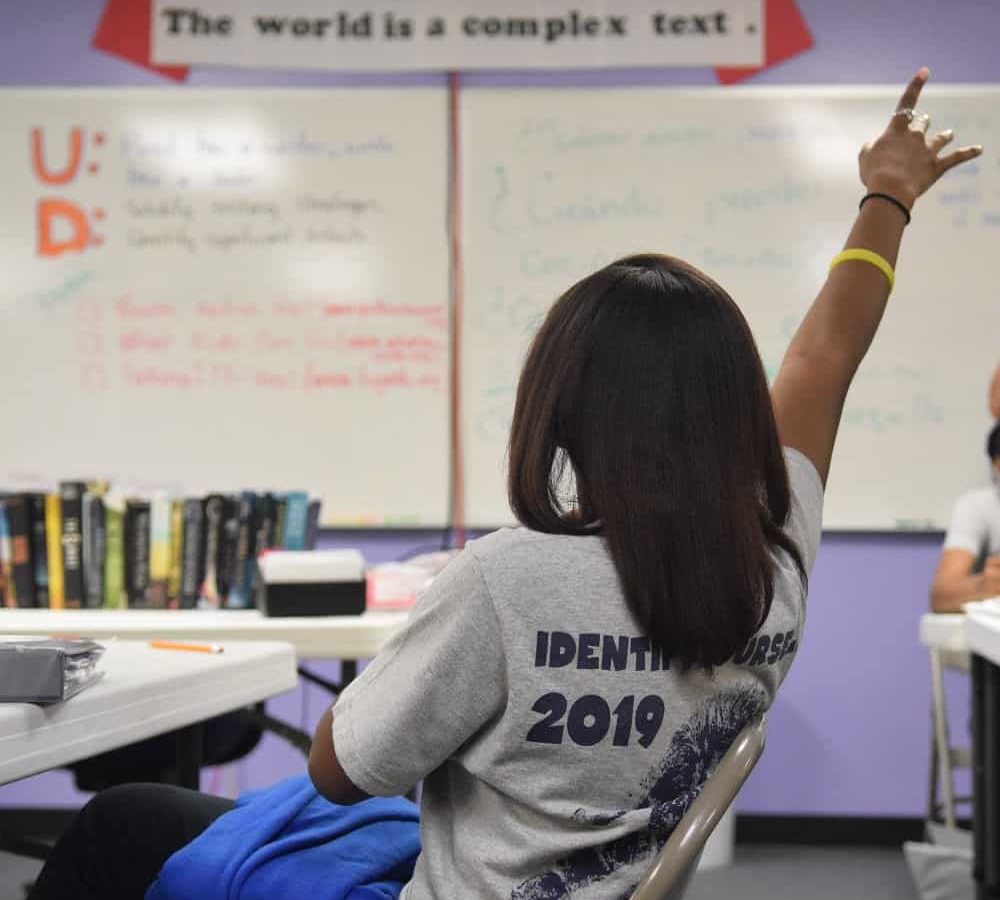

The world is a complex text

The feature photo of this article is among my favorite photos from my travels to schools. Even with 30 years of experience studying education policy, it didn’t hit me when I took it like it hits me now.

These policy proposals are complex, and so is the context within which they are being proposed.

The inter-relationship of this cohort of policy proposals requires us to assess the impact on local, state, and federal funding; the impact on students and educators; the impact on classrooms, schools, and districts, just as we emerge from the pandemic; and not just the first year the policies would take effect, but with an eye toward the future of our state.

On one hand, our system of public education has not well-served too many kids for too long. That is why our courts have found and upheld a constitutional right to access to a sound, basic education. That is why Teach for America’s vision statement is that one day all children will have the opportunity to attain an excellent education. That is why EdNC’s mission is to improve the performance of the state’s public schools.

On the other hand, our public schools are the school of choice for most of our families in North Carolina. Most of our families love the public schools their kids attend. Want to know one reason why? Because if they don’t, they find one that they do love. Many have been exercising choice all along.

But once parents find that fit for their child, the attachment is visceral. There is nothing like talks of closing or consolidating public schools to get parents fired up — or to get them to vote for a candidate not of their political party. Just search for “news articles from North Carolina about closing or consolidating schools.” Even where it might make sense financially, it raises questions about “community identity, cohesiveness, and social investment.”

The timeline of these changes will matter. Currently, most parents apply for “Opportunity Scholarships” between Feb. 1 and March 1, finding out in April if they are awarded. That means in spring 2024, as superintendents are presenting their budgets for the next school year to school boards and county commissions, we will find out if and how these policy changes impact their budgets as well as their students, teachers, classrooms, schools, and central offices.

To the extent the closing of schools emerges as a response — and here is the most recent infrastructure report so you can predict where that may happen — the local elections in 2024 may be just as polarized and politicized as we expect the national elections to be.

A couple of things to keep in mind:

- It is easier to tear things down than build them.

- We need to center our students. Choice for the sake of choice is not in their best interests.

- Systems are best designed and adequately funded when they can continuously improve and sustain excellence.

- The challenges and opportunities encountered with the mixed-delivery model for early childhood education should be considered as the K-12 system move towards this model.

Our history: The rise of our public schools

This history of education in North Carolina was published by the N.C. Department of Public Instruction in 1993. I had just graduated from law school.

It was Rupen Fofaria’s idea to dig it up because, as he says, none of us remember what our state was like before we had our now 2,700 public schools across North Carolina — or why they now exist.

“Strong leaders over the years have taken political risks for our children.”

— Bob Etheridge, then state superintendent of public instruction

Did you know the first public school in North Carolina was in Elizabeth City in 1705?

Did you know that school choice is not new to North Carolina?

In 1840 there were 632 common schools with 14,937 pupils, an average of less than 24 pupils per school. At the same time there were 140 academies with 4,398 pupils, an average of just over 31 pupils per academy. By the outbreak of war in 1861, there were approximately 4,000 common schools with 160,000 pupils, an average of 40 pupils per school and 350 academies with approximately 15,000 pupils, an average of almost 43 pupils per academy.

At the time, academies were authorized by the legislature, privately owned and operated, but did not receive public dollars.

This rise in public schools happened because:

For the majority of North Carolina children, educational opportunities were almost non existent. This was particularly true in the more rural areas, where sparse population, bad roads, poverty, and prevailing illiteracy often combined to create a self-perpetuating cycle of illiteracy and economic depression that was to haunt the people of North Carolina during the early days of statehood.

Public education across North Carolina has come a long way since then, and come a long way in our urban and rural areas. Education is inextricably linked to North Carolina’s recent ranking as #1 for business, which was awarded, according to the CNBC headline, “for putting partisanship aside.”

There is a lot at stake.

What you need to know: Federal level

There is no federal constitutional right to an education. Education is a state right.

But the federal government has influence on our system of education because it tethers the provision of federal dollars to our implementation of federal policy.

According to a recent report, North Carolina is among 15 states that will be at “a particular disadvantage” when federal funding for COVID-19 relief expires in 2024. Why? Because Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds represent a higher percentage of our overall education dollars, the report finds, and our districts serve more students in poverty, and more of our districts are high-need.

It is not just that “cliff” that has superintendents worried.

The fiscal year of our federal government runs through Sept. 30. If a deal hadn’t been reached to suspend the debt ceiling and federal dollars had stopped flowing, it would have created a real pain point for superintendents in July ahead of the start of school.

Also worth noting was the education-related policy proposals that were on the table as part of the negotiations. At one point, 3,300 teaching positions in North Carolina — funded by Title I for low-income students and IDEA for students with disabilities — were at stake, according to this fact sheet from the U.S. Department of Education.

The debt ceiling will be taken back up in January 2025. That leaves the next round of negotiations to the president elected in the November 2024 elections.

Districts that count on federal funding for more than 10% of their funding should pay particular attention.

Some presidential candidates are calling to eliminate the U.S. Department of Education. Former Vice President Mike Pence proposes instead for federal dollars to be distributed via block grants that states could use to fund school choice.

The latest negotiations of the country’s debt ceiling teach us that the role of the federal government and federal funding should not be taken for granted by superintendents and school boards.

Or our policymakers.

What you need to know: State level

The state budget: revenue and appropriations matter

How we choose to spend our money as a state is an indication of our priorities.

That starts with tax policy, which determines how much revenue will be available to fund our priorities.

When we evaluate the legislative proposals on taxes, we look at cuts to taxes but also whether the tax base would expand or contract and if additional sources of revenue are being considered. We also look at the revenue projections over time based on changes to tax policy.

The Senate budget proposes state appropriations of $11.4 billion for K-12, and the House budget proposes $11.7 billion. Here are the legislators on the conference committee.

It is important to remember that about $7.2 billion of the state appropriations compensates educators. Our educators need to be paid more — and other conservative legislatures are considering much higher pay increases than those proposed in North Carolina — but consider also all the other things that have to be funded with the remaining dollars. That’s why classrooms and schools and districts feel like resources are scarce.

The House budget proposal is better for education not just because it is more money. From parental leave to master’s pay to across the board raises for educators, it values educators more than the Senate proposal, which only includes a $20 per month raise for educators with 14 or more years of experience and increases funding for vouchers more than it increases funding for the teacher salary schedule.

Once we have a budget, you can count on EdNC’s reporters to share where the legislature lands on revenue and expenditures.

The expansion of school choice

On market share

When we talk about market share, we are talking about how many students are choosing traditional public schools, public charter schools, private schools, and home-schools in each district.

The market for students — and teachers — happens locally, usually within a county, but parents and teachers cross county — and state — lines.

Market share research is complicated because researchers don’t agree on the denominator.

Many estimates of market share add up the total number of students attending those types of schools and use that number as the denominator. EdNC’s last look at market share encouraged superintendents to look at the number of students they should have based on demographic estimates and projections from the Office of State Budget and Management or the Census Bureau, and to use that number as the denominator. It makes for messy data, but it gives districts a sense of how many students are not in public school for any number of reasons — from human trafficking to boarding schools.

The last time EdNC looked at market share for traditional public schools, the median was 75%.

The number of charter and private schools within a reasonable (as determined by the parents who do the driving) distance influences the pressure superintendents will feel, and the additional capacity of those schools will influence how quickly superintendents feel the pressure. District to district, that pressure will be different.

State reports on private schools and homeschools are released in July.

Market share matters because our traditional public schools and charter schools are funded based on the number of students they serve.

Charter schools

Here is the most recent report to the legislature and presentation to the State Board of Education on charter schools.

North Carolina started its experiment with charter schools with a cap of 100 in place. That cap was removed, and when school starts in August, we expect there to be 211 charters statewide.

Since 1998, there have been a total of 87 charter terminations.

Data that is self-reported by charter schools indicates that there are about 77,000 students on waitlists for charters statewide. That gives you a sense of demand.

Several policy proposals are increasing tension between traditional public schools and charter schools.

A policy change to the role of the N.C. State Board of Education could lead to an increase in the number of charter schools statewide. Currently, recommendations of the Charter School Advisory Board are run through the State Board — a check and balance on the expansion of charters statewide.

A policy change is proposed that could increase the dollars traditional public schools must share with charter schools.

Two highlights about charter schools from the recent report: 18% of traditional public schools are identified as continuously low-performing, 17% of charters are identified as continuously low-performing, and it appears traditional public schools meet or exceed growth at higher rates than charters.

From my travels to schools across North Carolina, here is how I make meaning of that. Regardless of school setting — traditional public, charter, private, or home-school — there are always some that are good, some that are not so good, some that are getting better, and some that are getting worse.

Those trajectories are influenced by a lot of factors, including the leader of the school, the experience and quality of the educators, whether the leader has the buy-in of parents and teachers, whether the leader has the support of the district, the demographics of the students serve, the adequacy of resources to support the instructional process, and on and on. The provision of education is dynamic in any setting.

What we learn is that policy changes should be evaluated, in part, by assessing whether the change makes it more likely for schools across settings to continuously improve and sustain excellence.

Please note that the proposed expansion of school choice, which is discussed next, would impact both traditional public and charter schools.

Also note that religious charter schools may also be on our horizon.

The expansion of vouchers to private schools and home-schools

The policy changes proposed would allow parents to choose on behalf of their children whether to take the state’s investment in their child — called the per-pupil expenditure (PPE) — and use it to cover the costs of private schools or home-schools. This option would be available for the first time to all parents in North Carolina, and how much money families would get would likely depend on family income and whether the child would be educated in a private school or home-school.

Here is where you can get more information about the Opportunity Scholarships and Education Savings Accounts available in North Carolina currently.

Legislators themselves are hashing out the details of the policy proposals now. Here is the Senate’s proposal, and here is the House’s proposal.

A couple of things to keep in mind:

- While the family will get a percent of state PPE through the Opportunity Scholarship, the district will lose the full amount per pupil.

- Stabilization funds for districts have not been proposed as in other states. Sen. Berger is on the record saying, “It makes no sense to me to provide money to the traditional public schools for children they’re no longer educating.”

- Unless federal policy changes, parents would be forgoing the federal and local government investment in their child.

Here is an example of that last point. In Edgecombe County, the state provides $8,666.49 per student.

What we aren’t talking out loud about yet is the federal government investment of $3,516.78 per student and the local government investment of $1,582.40 per student in Edgecombe County. Over 13 years of K-12, that’s $66,289 of public investment per student that is at stake. Think about that across our 1.5 million students and over time.

Here you can see federal, state, and local PPE by district with dollars for child nutrition included.

How much public money will not be invested in our students, in our workforce of the future, and what will that mean for our capacity to attract industry to North Carolina and remain #1 for business?

Over time, the policies proposed make it seem likely that vouchers will be phased out and personal education savings accounts (PESAs) would be phased in.

In other states, parents can choose to save the money in the PESAs for college. It’s important to make clear to parents electing to do so that the options for a student’s college are dependent on the school experience that leads up to admission. It’s also important to be transparent with parents choosing vouchers for private schools that our elite private schools will remain unaffordable to most even with the state subsidy.

Here is an explainer from FutureEd on the public funding of private schools.

Funding for our seniors

Another proposal would require high schools to offer a path to graduation in three years. For the purposes of this analysis, the upshot is the potential loss of average daily membership (ADM) for seniors in districts across the state. This school year, we have 100,853 high school seniors.

The funding model

A change in how we fund schools has also been proposed, which would move us from allotments to a weighted student funding formula. The big question would be whether the baseline investment in each student is adequate.

Other policy changes that could impact public education

There are a variety of other policy proposals being considered that could have a big impact on public education.

There is a proposal to elect the State Board of Education. Since our state already has an elected state superintendent, this would make us the only state in the nation where both the superintendent and state board are elected.

There is a proposal for an advisory commission on the standard course of study.

There are proposals for open enrollment in districts.

There are proposals that would impact discipline in schools, particular groups of students including our LGBTQ+ students, and access to literature.

And looming for educators is a proposal to shift the health insurance provider for state employees, including educators, from Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina to Aetna.

What we are hearing

Based on our reporting, research, and travel, it is the collective impact of these possible changes that superintendents, school boards, educators, and the public need and want to better understand. It is a lot of change in a relatively short period of time at at time when leading a district or serving in a classroom is already stressful.

Considerations for our state policymakers

Most of the policy changes as currently proposed would not take effect until the 2024-25 school year.

Here are some concerns we are hearing on the road:

- Please consider a study commission between the long and short session to ensure these policies and their impact are discussed and evaluated. It would be good for you to hear what superintendents have to say, and it would be good for them to hear what you have to say.

- Once it is clear which of these policies are moving forward, the state needs 10-year forecasting for average daily membership by district that takes into account charter and private school supply and how quickly supply can be increased. There are good firms that have developed good algorithms that provide good data for decision-making. The algorithms take into account, for example, religious preferences within a county and private school supply relative to those preferences. They take into account the number of children in a household and poverty and assess the likelihood of choosing to home-school relative to those factors.

- A playbook on how to downsize or rightsize districts aligning resources and staffing to shifting ADM needs to be written to help superintendents.

- There will be what district leaders call swirl. Parents that choose charters, private, or home-schools will change their minds. We need to consider mid-year capacity for public schools to absorb students and compensation for swirl.

- If the state is not going to consider stabilization funding for districts, it might consider phasing in access to vouchers to control the impact on districts. It might also consider a stabilization fund that could be administered by DPI.

- Once we have a better sense of how many parents and which parents choose vouchers, there will need to be research conducted about how to better educate the students that our public schools serve given the anticipated shifts in those demographics. Teacher match and equitable rostering, for instance, and other instructional practices that are designed to make sure all students are served well will need to be prioritized.

- And there is concern about accountability. Research shows 1 in 100 caregivers in North Carolina have documented abuse or neglect when it comes to their kids. Educators, parents, and community members all serve as checks on one another in protecting our children.

If you are going to implement these changes, please allocate the time and resources to do it well.

And expect parents to have a lot to say.

EdNC just conducted a survey of parents in western North Carolina. We are still analyzing the results, but the participation was incredible. More than 3,000 parents responded, and all open-ended questions shown to all participants received between 1,178 and 1,973 comments, helping us understand how parents make choices about schools for their students, what they love about their schools, and the challenges they experience and opportunities they hope for.

Considerations for our superintendents

If you have never studied change management, it is time to start.

Here is what we are hearing on the road:

- Think and act like one of the largest employers in your county.

- Take a hard look at your fund balance. Fund balances, which operate as savings accounts for districts, matter now more than ever as federal COVID-19 relief funds sunset, given the need to be able to buffer shifts in ADM stemming from the proposed state policy changes, and also ahead of January 2025 when the next debt ceiling negotiations take place.

- If federal funding accounts for more than 10% of your budget, save more.

- If the state doesn’t provide it, find money for ADM forecasting.

- Become experts on your local market share.

- Find money for marketing, enrollment, and retention.

- Parent to parent conversation is going to be critical for enrollment and retention. Consider making signs available to families on the first day of school that say “proud family of [add name of school]” for parents to put in their yards. Consider parent hotlines.

- If you don’t have a foundation, you need one. Foundations help districts weather market share shifts and the unpredictability of state and federal revenue.

Remember parents needs to believe there is a good fit for their students in public schools before they will advocate for public education — and that holds true across demographics, geography, and ideology.

The timing of these changes coming on the heels of the pandemic and set against the backdrop of the 2024 elections makes this harder for you. Thank you for your leadership and public service.

Considerations for our philanthropists

Your return on investment is at its highest now. It costs less to invest in proactive stabilization then it will cost to address districts in crisis.

Here is what we are hearing on the road:

- Study the role of philanthropy in Medicaid expansion, and think about what that means for this statewide issue.

- The landscape just changed. Invest in nonprofits doing the work. Invest in coalitions.

- Maryland is the state that has made the biggest bet on public education. Study that initiative and its momentum, and consider how it could be replicated here.

- Support districts in marketing, enrollment, and retention campaigns. A regional study of best practices for districts could help districts across the state.

- Support research on forecasting and market share, and playbooks on downsizing and rightsizing.

- Help districts establish foundations. Teach them how to raise money from individuals, corporations, and philanthropy.

Considerations for parents, educators, and public school advocates

It’s OK to talk out loud about our public schools

Our public schools offer an abundance of choice: year round, charter, magnet, language immersion, single sex, early college, career academies, virtual academies, alternative schools, lab schools, and on and on.

They are the largest employer in most of our counties.

Think of all the types of workers they employ, from plumbers to principals.

Think about their role as anchor institutions in our communities. They often have the largest commercial kitchen in the county. They provide after school care. Many provide summer camps. They are our shelters in emergency. They are part and parcel of our community identity. Take in a Friday night football game in a small town this fall and see.

What can you do?

Read EdNC. We love it when you like our articles on social media, but when you share our articles you extend our reach.

Work to slow things down so that the implication of policy changes can be understood and prepared for by schools and districts — for example, advocate for a study commission.

Work to change the policies — for example, adding stabilization funding.

We believe in the power of the “go and see.” Invite your legislators to visit your child’s classroom with you. Explain to them why it’s a good fit for your child.

Recruit educators to run for office. In other states having an educator run for office in every single county helps keep public education in the headlines and on the agendas of politicians.

Build coalitions, even unexpected coalitions. In Texas, small, rural, conservative districts banded together because of the importance of the schools to town identity. And then they started working with large, urban districts.

Think about the role of the business community and chambers of commerce. Reach out to small and medium-sized businesses in your community. They need an educated workforce.

Think about how policy changes and advocacy align with the state’s 2030 attainment goal. Across party lines, people and policymakers want more workers to have the opportunity for a family-sustaining living wage.

What is EdNC’s role?

EdNC is uniquely positioned to document the state of public education as we know it in the next school year in all 100 counties.

And in the following year, we are uniquely positioned to document the impact on students, educators, classrooms, schools, districts, and communities as these policy changes are implemented.

We believe there is power in being able to tell the story and collectively writing the history of what is happening to the schools across our state from Murphy to Manteo.

As a reminder, this is our mission:

EdNC works to expand educational opportunities for all students in North Carolina, increase their academic attainment, and improve the performance of the state’s public schools.