This is the second article in a series on faculty pay at North Carolina’s community colleges. Click here to read the rest of the series.

“It is more and more difficult to keep great faculty in the classrooms and labs. They can make more money elsewhere. Especially in high demand fields like allied health and industrial programs, when income is a driving factor we simply cannot compete.” – John Gossett, president of McDowell Technical Community College

North Carolina’s community colleges, like any service-providing organizations, devote the bulk of their annual budgets to personnel costs. At Wake Technical Community College, for one, $64 of every $100 in operating expenses went to salaries and benefits in fiscal year 2018-19.1 The $129 million spent supported 2,286 employees, of whom 933, or 41%, were instructors.2

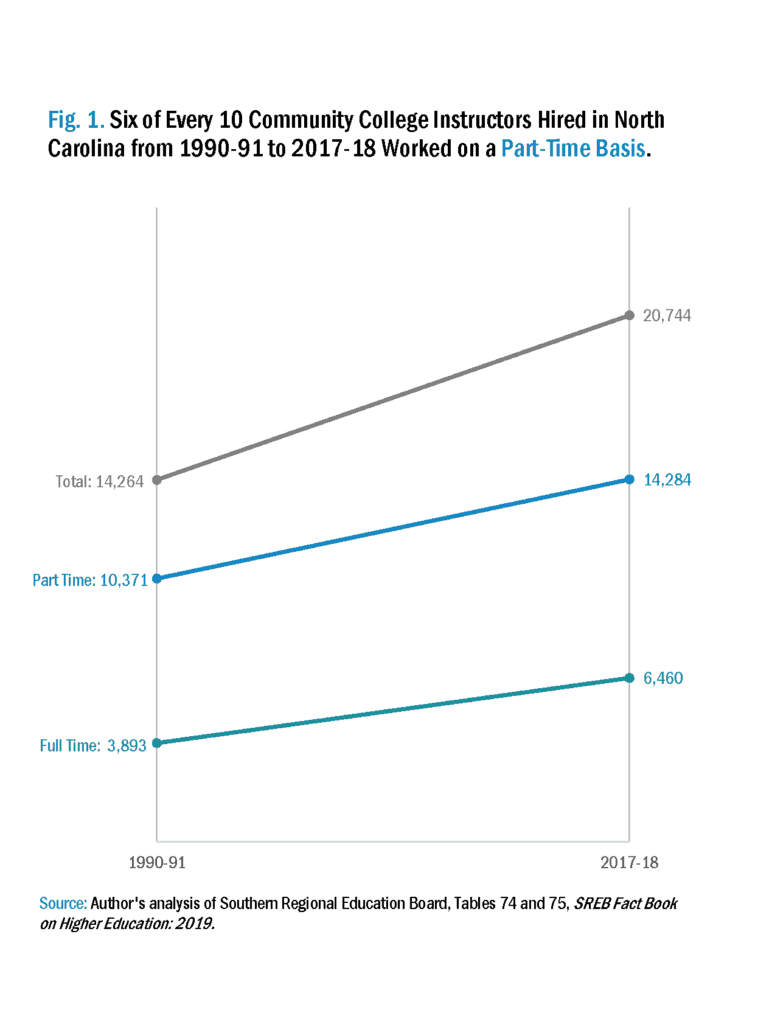

A total of 20,744 faculty members worked in North Carolina’s 58 community colleges in 2017-18, according to the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB), a regional interstate compact organization focused on education policy.3 Some 6,460 of these individuals, or 31%, worked on a full-time basis, the remaining 14,284, or 69%, on a part-time basis.4

Demographically, based on data from the National Center on Education Statistics, a unit of the US Department of Education, 84% of North Carolina’s full-time community college instructors identify as non-Hispanic White persons, and 10% identify as African-American persons.5 The SREB further estimates that women account for 58 of every 100 full-time instructors in the state, a share exceeding the national and regional one.6

A growing, primarily part-time faculty corps

The total number of community college instructors in North Carolina grew between the 1990-91 and 2017-18 academic years, according to SREB data. Over that period, the total number of instructors (full- and part-time) rose by 45%, climbing to 20,744 from 14,264.7 Growth in the faculty corps is unsurprising since total enrollment (headcount) also rose by 45% during that span of time.8

Employment has increased for full-time and part-time instructors (Fig.1). From 1990-91 to 2017-18, the number of full-time instructors grew by two-thirds, which translated into a gain of 2,567 instructors.9 The number of part-time instructors grew by 38%, or 3,913 positions; put differently, part-time jobs accounted for six of every 10 positions added since 1990-91.10

Despite the larger number of part-time instructors, the composition of the faculty corps has shifted somewhat toward full-time instructors. In North Carolina, 69 of every 100 instructors worked on a part-time basis in 2017-18, down from 73% in 1990-91. The national share, in contrast, rose to 67% from 57%, and the share in SREB member states climbed to 65% from 60%.11

As will be discussed, state appropriations are the main source of faculty salaries, with colleges receiving funds based principally on an enrollment formula.12 Community colleges also are “open door” institutions that must accept all qualified students, but enrollment tends to be countercyclical, rising during recessions and falling during expansions.

These realities complicate staffing at community colleges in ways unseen at University of North Carolina (UNC) schools, which simply can cap enrollments to match available resources. Using part-time instructors who are paid less helps community colleges navigate the enrollment and finance maze, even if, as will be explored, it may detract from a college’s mission.

College professors with a twist

Instructors at two-year colleges typically possess academic qualifications similar to those of their counterparts at four-year universities, and in the case of college-transfer programs, community college instructors often are teaching the exact same courses as their UNC peers. Yet instructors in two-year institutions differ from their UNC colleagues in three key respects.

First, community college instructors simply are paid less.

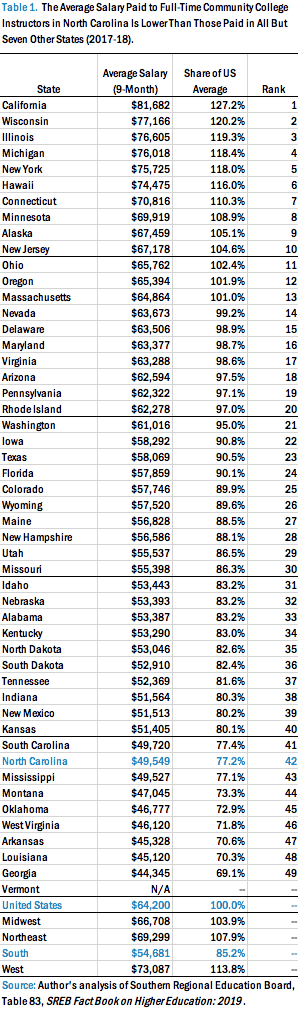

SREB data show that the average full-time community college instructor in North Carolina earned $49,549 in 2017-18, which was well below the national average of $64,200 and the SREB average of $54,681. Nationally, North Carolina ranked 42nd on this measure (Table 1).13 Full-time UNC instructors, meanwhile, earned an average of $86,252, which was close to the national average of $86,777 and greater than the SREB average of $82,462. Nationally, North Carolina ranked 21st on this measure.14

“I would argue that there is parity of performance but not parity of pay,” said Walter Dalton, president of Isothermal Community College in Spindale and former Lieutenant Governor and member of the General Assembly.15 “We are teaching college transfer courses at the same time they are teaching them at the four-year institutions, but our faculty are getting paid less to do the same work.”

Second, unlike universities, community colleges typically lack academic ranks, which prevents instructors from enjoying the salary progression that occurs as they advance from assistant to associate to full professor.

Average annual faculty salaries in the UNC system rise from $75,361 for assistant professors to $84,506 for associate professors and then to $118,033 for full professors.16 In 2014, Wake Tech established a system of academic ranks under which high-performing instructors can become assistant professors after three years of service, associate professors after five years, full professors after seven years, and senior professors after 12 years; the achievement of each rank confers a bump in salary.17 Wake Tech’s interesting model is atypical, with most colleges having the single rank of instructor for all faculty members.

Finally, faculty members in North Carolina’s community colleges lack the tenure protections awarded at universities.

Community college instructors instead typically have annual contracts that become automatically renewable after the completion of three years of service.18 While community college instructors normally lack the research expectations placed on their university peers—expectations that can lead to controversial work for which academic freedom is crucial, the lack of tenure deprives two-year college instructors of a form of job security.