It’s Sunday morning. I’m sitting by my fire looking at the 2020 results from across this state I love so very much, wondering about the story we will tell ourselves about this election.

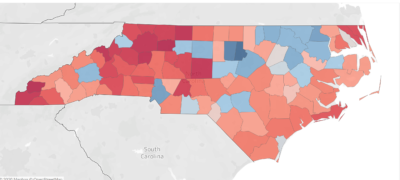

Based on who is leading in the unofficial results, which may change as more votes are counted later this week, here’s the lay of our land.

On Nov. 3, 2020, across North Carolina, there were 2,623,000 Democrats registered to vote; 2,231,586 Republicans; and 2,452,000 unaffiliated voters. According to the N.C. State Board of Elections, the total number of registered voters was 7,361,219 (a small number are registered with other parties), and voter turnout was 75% — up from 69% in 2016.

President Donald Trump won 75 of our 100 counties — in 23 counties with 70+% of the vote and in another 27 counties with 60+% of the vote.

Urban counties — our economic engines — voted for President-elect Joe Biden: Durham with 80.42% led the way, followed by Orange with 74.82%, Mecklenburg with 66.68%, and Wake with 62.25%.

Republicans Richard Burr and Thom Tillis will represent our state in the U.S. Senate.

In the U.S. House of Representatives, five Democrats and eight Republicans will make up our delegation.

Democratic Governor Roy Cooper was re-elected, but the Council of State includes six Republicans — including Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt — and three Democrats.

2020 was a 10-year election, and with Republicans maintaining control of the House of Representatives and the Senate in the North Carolina General Assembly, they will control redistricting for the decade to come.

In this map, you can explore which party won school board and county commission races by county. It also gives you a sense of how red or blue or purple our counties are.

How did we get here?

Back in 1994, just after I graduated from law school, Republicans gained control of the N.C. House for the first time since the 1800s and the N.C. Senate was narrowly held by Democrats (26-24). I have been writing about the evolution of party politics across our state ever since.

What I remember about back then is at that time, North Carolina was thought of as a “good government” state, in part because of the relatively low incidence of scandal and corruption.

It was a time when “bless his/her heart” was the go-to not nice thing to say about someone behind their back.

Jon Tester is a U.S. Senator from Montana. He is a Democrat. He is also a farmer and a former elementary school music teacher. The state he serves is rural and conservative — interestingly, there is no party registration in Montana, but the state voted 56.7% for President Trump. He published a book earlier this fall entitled, “Grounded: A Senator’s Lessons on Winning Back Rural America.”

In an interview with NPR, Tester said, “what I see politicians doing a lot in rural America is, number one, they tend to pigeonhole people and think that maybe they aren’t the smartest people on earth when, in fact, they’re just as smart as anybody else, maybe that they’re not as motivated when, in fact, they’re just as motivated as anybody else.”

What worries me most about First Lady Kristen Cooper’s recent post on Facebook is her use of language confirms Tester’s theory. Cooper described a conservative family protesting outside the governor’s mansion in Raleigh as “pitiful” and “a bunch of clowns.” WRAL reports Cooper apologized and that the organizer of the protest sent a letter to Cooper asking to meet face-to-face.

Which brings me to the ongoing importance of coffee.

Two business principles have been at play in politics, policy, and the media nationally and in North Carolina — availability and confirmation bias. People base their perceptions on information that is easiest to come by — that’s availability. But availability is complicated by confirmation bias. People seek and consume information that confirms what they want to believe.

Our own personalized echo chamber results. The decline in local, and especially rural journalism, which often has its pulse on local trends, hasn’t helped. Nor has the increase in social media, which both allows people to further limit their own exposure to people with diverse views and provides a venue where people are more willing to say things they might not say in person.

An article on the psychology of social media notes that “talking face-to-face is messy and emotionally involved.” And this podcast on the Hidden Brain looks at our political division and how it makes us feel helpless and hopeless. It argues that our division is less between Ds and Rs and more between those who are deeply involved in politics — as in preoccupied with it — and the rest of us. The rest of us, it turns out, aren’t so comfortable talking politics, so if there is a risk of political conversation, then the conversation may be avoided all together.

Back in February 2018, when he was visiting North Carolina, Jeremy Anderson, president of Education Commission of the States, said in states where leaps and bounds are being made, leaders have found ways to work across difference. “It’s a simple litmus test,” he said. “Can the people who can move this policy meet for coffee even if they disagree and talk through some of these differences?”

We’ve been asking people to share coffee ever since.

So you can imagine my deep sadness, when on Oct. 29, 2020 — five days before the election — in an article, “Three gubernatorial contests with important ed implications,” Dale Chu wrote in a paragraph about a civil debate between our candidates for superintendent of public instruction, “The goodwill should be short lived. No matter what the outcome, North Carolinians can expect the resumption of the inescapably partisan approach that has come to characterize the state’s education politics.”

Should? Why should?

Inescapably? Why inescapably?

As best I can tell, Chu doesn’t have ties to our state. But it’s important to understand how we are seen and how narratives may feed a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Heeding President-elect Biden’s call

In his speech on Saturday, Nov. 7, the day the AP called the election, President-elect Joe Biden pledged to be a president who seeks not to divide but to unify. A president who doesn’t see red and blue states but a United States. He said it was time to see each other again, to listen to each other again. He said he would work as hard for those who didn’t vote for him as for those who did.

We need policymakers across North Carolina to heed President-elect Biden’s call. To unify instead of divide. To see and listen and be in relationship with all of the people who call North Carolina home. To work for all the people they were elected to serve regardless of their party registration, regardless of who they voted for.

Biden said, “The refusal of Democrats and Republicans to cooperate with one another is not due to some mysterious force beyond our control. It’s a decision. It’s a choice we make.”

Let’s make a different choice, North Carolina. Our stomp-your-feet/standoff/stalemate strategy — I’ve heard it called all of those things — of the last couple years didn’t lead to a state budget or Medicaid expansion or raises for teachers or a sound, basic education for all of our children.

Scott Elliott, the superintendent of Watauga County Schools, said to me recently, “Children have a short precious few years with us and we shouldn’t ask them to be too patient with us.”

The future isn’t waiting, y’all. And our local, state, and federal revenue forecasts and economic outlook will make the moving forward even more complicated.

Biden called for “a nation united, a nation strengthened, a nation healed.”

Let’s issue our own call for a North Carolina united, a North Carolina strengthened, a North Carolina healed. We can do hard things.

Getting to know our state again, starting in Cherokee County

When we don’t see and listen, as Biden called for us to do, we imagine what people and places are like — and our echo chambers make our ability to do that less accurate.

This fall, I have been traveling throughout southwestern North Carolina. With the exception of Buncombe, all of these counties voted for President Trump.

Last week I was in Transylvania, Jackson, Clay, and Cherokee counties. The week before I was in Swain and Graham, and this week I will be in Polk. I wish you could all come with me.

Do you know about the Republican leaders in Transylvania County who broke ranks with their party? “When they pondered their political future,” noted an article in The New Yorker, “they hoped that becoming actively nonpartisan might inspire voters to focus on their work — schools, mental health, early-childhood education — and not labels, or the national wedge issues that don’t mean much in local governance.”

Recently, to help people understand the strength of rural places, EdNC released this video about Clay County.

And then there is Cherokee County, way out west.

Murphy in Cherokee County is just more than 350 miles from Raleigh. Cherokee County voted 76.91% for President Trump and Republicans garnered more votes than Democrats down ballot too.

Cherokee County is home to Tri-County Early College, a model for early colleges around the country and the world.

This purpose of my visit was to meet Paul Worley, the director of economic and workforce development for Tri-County Community College. He describes himself as apolitical.

Worley explained to me that Cherokee County is part of what he calls a “geographic bowl.” The county borders Georgia and Tennessee. There is a gorge on each end and mountains all around. Three counties in North Carolina, three counties in Georgia, and one in Tennessee together “basically create a retail and workforce shed,” he said.

Unlike other counties in North Carolina, the community college serves as the economic developer for Cherokee County.

Here, Worley explains how industry has transitioned in the county since the time of railroads.

“We don’t know what’s next,” says Worley, but he does know what he wants. He wants jobs in his county that pay higher wages and benefits.

“You don’t know workforce development,” he said, “until you have had to be rapid response to people losing their jobs.”

It feels different when they are your friends and family and people you grew up with, he said.

His biggest public policy concerns? Access to broadband, housing, supply chain disruptions, and too few OB-GYNs.

Fiber broadband is delivered along the existing poles used for electricity across the county, and only two things stand in the way of what’s called last-mile connectivity — which just means everybody has access to high-speed internet. Some of the land in Cherokee County is tribal, which requires its own easement, and enough people have to be able to afford the internet to make it worth it to hang the fiber the rest of the way.

The tan area is tribal property.

That loop of cable is fiber.

In terms of housing, Worley said he needs 100 rental units tomorrow. Eight-hundred houses have sold in 2020, he said, and only 200 are on the market now, with only 55 in the 150-200K range.

He also worries about supply chain disruption, starting our conversation by talking about the butterfly effect. “Everything in the world,” Worley said, “revolves around the supply chain.” That makes him worried about COVID-19 and education and the impact of this disruption on the supply of future workers.

“We are affected more by what happens in Georgia and Tennessee,” he noted. It’s the public policies of three states he is having to keep track of.

If policymakers in North Carolina are looking for something to do that can help Cherokee County quickly, Worley says they need to be able to charge in-state tuition at the community college for the students in contingent counties. Forty percent of his workforce comes out of north Georgia.

And they need more OB-GYNs. Turns out people like to have their babies where they live. I checked, and in 2019, according to the Sheps Center at UNC, there was 1 OB-GYN in the county and no certified nurse midwives. There are 28,612 people countywide, and there are about 250 births each year.

Worley has learned you can’t do workforce development on your own. “We don’t really have anybody that doesn’t work together out here. We don’t have a choice.”

So he has two rules.

“Don’t take credit unless you are willing to take the blame.”

“We don’t set policy. If you want to set policy, get elected.”

To the elected

The art of governing is different than the art of getting elected.

Hear Biden. See and listen to our people.

Hear the protestors in our cities. Try to understand that, as one teacher said, “behavior is communication.”

Hear the concerns of those living as far away as Cherokee County.

Seeing and listening is harder right now because of COVID-19. But if there is a place you want to go and see, just let me know.

We are willing to do whatever it takes to create opportunities for more people, philanthropists, and policymakers across lines of difference to be in relationship with each other as we move forward together.