It is clear that Adam Haigler’s teaching style is built off strong relationships with his students. Consider how he started class one Tuesday during ninth-grade seminar, 30 minutes set aside daily for building students’ life and career skills at Tri-County Early College in Murphy: “Alright homies.”

Haigler is a biology and environmental science teacher at Tri-County, an early college in rural Western North Carolina recognized across the state’s Cooperative Innovative High School (CIHS) network as a leader for its project-based learning, competency-based assessment, and innovative teaching practices. Show up for a day of Tri-County classes and prepare to see teachers and students who want to be there.

Haigler went on to have students write two connected phrases, each on a sticky note, like Batman and Robin or mouse and cheese. As students stood in a semicircle with their backs to the center, two volunteers placed a random sticky note on each student’s back. The students were then instructed to find what was written on their notes by asking their classmates yes or no questions. After they confirmed their notes’ contents, they had to find their matching phrases.

In a discussion after the exercise, Haigler asked students why they thought he chose the activity. Once a student landed on “communication skills,” Haigler asked, “In what ways will this help you today?”

One student answered, “I’m nervous I won’t get respect as the youngest person in my group project.” Many students raised their hands as Haigler asked if anyone struggled with communication on their latest group project. He led a discussion around the importance of communicating clearly and working together.

Even though it was a simple game in an extra period, students took the exercise seriously and were engaged in the discussion afterwards. It seemed they knew Haigler cared about the questions he was asking.

Depending on the day of the week, seminar at Tri-County has different focuses like mindfulness, smart goal-setting, and career and college planning. Haigler said the period is an intentional way the school uses to create trusting and respectful relationships between instructors and students.

“That’s a part of our system that really helps provide kids with skills beyond just (academics), and lets them know they have an adult who cares about them and is looking out for them,” he said.

Tri-County’s early college model allows students to start taking college classes at Tri-County Community College in the ninth grade. The school’s target population as a CIHS is highlighted on the home page of its website: “first-generation college-goers, those at-risk of dropping out or other historically underserved populations.”

If students are struggling, Haigler said they provide more and more support. They look for ways to give students opportunities to redeem themselves rather than punishing them with poor grades.

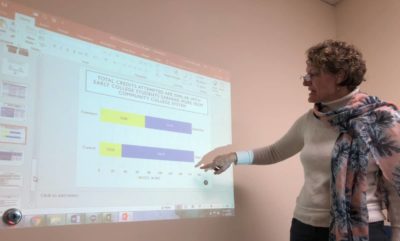

Students at Tri-County earn an average of 69 college credits by high school graduation, and the majority earn an associate degree. The early college model creates an opportunity for students to save money and time and enter the postsecondary world more prepared to succeed. The school has a 100 percent graduation rate and an 88 percent college-staying rate.

“They enter (college) as juniors, and our students from this school enter as leaders often times,” Haigler said. “They come in and they’re leading their junior classes. They’re forming study groups. They’re tutoring other students. They know how to work in groups, they know how to think critically. They know how to take an open-ended task and break it down into its constituent parts and delegate.”

But that isn’t just because students are taking college and high school courses at once. On top of adding the college experience, Tri-County has changed almost every part of the high school experience.

‘Leading edge in terms of innovation on all fronts’

Tri-County’s high school curriculum is built entirely around projects. There are three-week breaks in between the semester-long projects, but the rest of the time, all subjects are taught through the project’s lens. This year, back by popular demand, teams of students are tackling seven different real-world court cases.

“How could you tie in your case to my curriculum?” Haigler said he asks students. “Biology students are thinking about DNA. How is DNA used in the legal system? How could DNA relate to my case? Or one group is looking at climate change… that’s clearly connected to my class content as an environmental science and biology teacher. They can find those connections.”

A student group worked on the case on climate change, which is expected to go in front of the Supreme Court next fall, each of them researching and making plans on their iPads. They needed to come up with three theories for both the prosecution and defense, as they wouldn’t know until later in the semester which side they would have to take.

One student excitedly shared a theory he had come up with. He opened the Preamble to the Constitution on his screen and read, “and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity…” Looking up, he asked his team, “Do you know what posterity means? All future generations!” He high-fived a teammate, explaining how this line could help them make the case that climate change is unconstitutional.

A few minutes later, another student in the group said, “I need to write everything down we said we’d do.” Another teammate was making deadlines for when they needed to reach certain benchmarks in the project.

Teachers act as guides through the process of discovery rather than telling students what to do each step of the way.

“They want to get down and dirty with you versus just be at the front of the classroom and just be out of the picture,” said Adam Fleischer, a Tri-County sophomore.

Students said the projects make them feel ownership over their learning. Junior Samantha Calascione, who is working on a murder case for her project, said the project helps her see topics in which she normally struggles, like math, in a new light.

“I’m able to take what I’m learning in my classes and apply it to real-world things that most people would never think about,” Calascione said. “It’s extremely helpful. When I can see how radians of a circle affect gunshot wounds like I’m doing in this, to see how all of that connects together blows my mind. It takes things that I usually wouldn’t find fun or entertaining and makes them extremely fun and understandable.”

Sophomore Cassie Lowrance said she is always surprised by how interconnected the different things she is learning are. In past school experiences, Lowrance struggled to retain information through lectures or simply reading. She said the hands-on approach at Tri-County has changed everything for her.

“Here, everything is related to the project. So you’re learning biology but you’re like, ‘Well this is how it affects the earth in this environmental court case,’ so it’s like, you can relate things you wouldn’t think would actually work. Usually, it’s not even far-fetched connections. It’s really closely related, which can help you actually remember the material.” Lowrance later added: “You get to use your own brain.”

Students still have to learn statewide standards and take state-mandated exams. To not only individualize learning but also the pace at which students learn, Tri-County uses competency-based assessment. That means once students feel they know a skill or have reached a standard, they can prove their mastery and move on.

Other than the state’s standards, instruction is built around Tony Wagner’s seven “survival skills,” which are abilities based on what professionals in the fastest-growing industries said they are missing from employees:

- Critical thinking and problem solving

- Collaboration across networks and leading by influence

- Agility and adaptability

- Initiative and entrepreneurship

- Effective oral and written communication

- Accessing and analyzing information

- Curiosity and imagination

Haigler pointed at his white board and explained how each item — a presentation, a research paper, an art piece — contributed to one of the skills. Students have to present twice a year and reflect on how they are doing in each category.

“It prepares our students with skills that make them a different animal frankly,” Haigler said.

Calascione said the rigor is intense and can be stressful, but constantly presenting and challenging herself has made a big difference in her skills and personality.

“I’ve been able to watch myself grow as a person, as a student, as a team member, as a leader, but I’ve also been able to watch my peers grow,” Calascione said. “… I’ve been able to watch people break out of their shells. And it’s not really that normal, you can crack it, then leave it for a little bit, then push it open. Here it’s like they hit it with a sledgehammer and you pick up the pieces as you go. I know that may sound a little harsh or crazy but it works.”

The stress of the environment is something multiple students mentioned, but they always added that they feel it’s worth the benefits.

“Stress is definitely something that you kind of … it’s like a headache that’s always there, you just got to get used to it,” Fleischer said. “But the stress I’d say is a good thing because it makes you want to do stuff. And when you get done with something, even a minor accomplishment, you just feel such pride and such joy that you did this.”

Ben Pendarvis, a Tri-County history and drama teacher, is working to share the project-based learning approach with other schools in the state through an organization called Constructive Learning Design. Pendarvis said the layers of innovation at the school have built off of each other.

“We feel like we’re definitely on the leading edge in terms of innovation on all fronts,” he said. “We’ve redesigned the whole model.”

Pendarvis said he thinks the innovation stems from teacher-led decision-making, which is empowered by Principal Alissa Cheek. Teachers are the ones who create the schedule and instruction around what they see as best for their specific students.

“We have changed our instruction to be real-world, community-centered, problem-oriented, solving real problems and acting in the real world, making an impact on the world, and collaborative, to match the kind of skills we want to see them going out with,” he said. “So we picked up competency-based [assessment] because we knew that that would more accurately reflect what they were learning, and we use PBL schoolwide because… we could do more with it.”

Haigler said the success they have seen at Tri-County does not just rely on the CIHS designation or early college model.

“Your high school has to orient around being a high-support, high-expectation environment.”