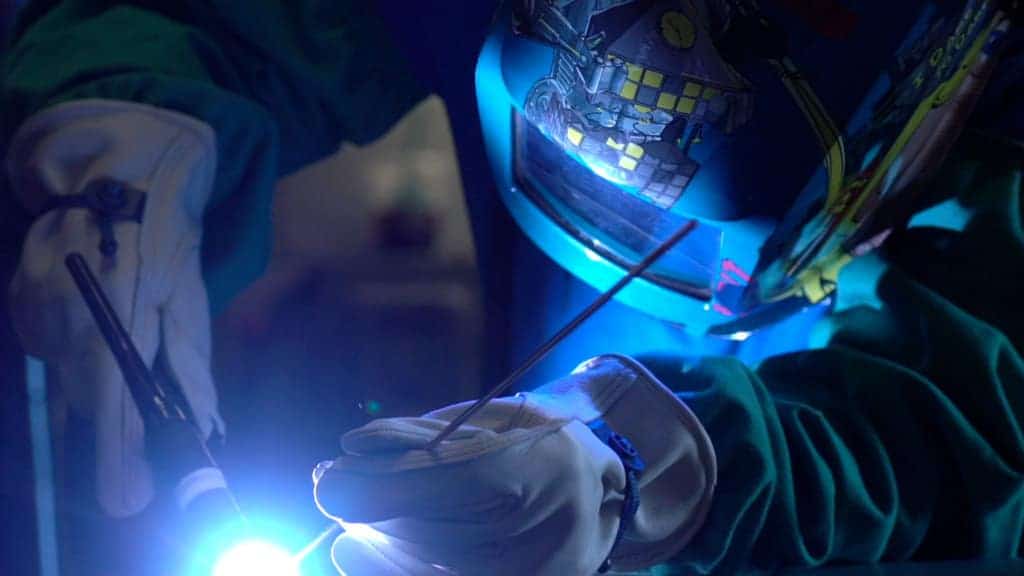

“85% of everything you touch each day in your life has been welded at some point.”

Michael Dixon, faculty welding instructor at Davidson County Community College, has taught around 1,000 students over a 14-year career. He says most people are surprised to find out that welding these days requires circuit boards and computers, not anvils, hot coals, and hammers.

He goes on to explain that the welding occupation was originally not declared as a single trade itself, because it falls into so many others. Construction, engineering, mechanical repair; you name it — “It it doesn’t matter what you’re doing, you’re going to need welding at some point,” said Dixon.

“And it takes more brains and less brawn to be a welder these days.”

In 2018, Dixon was awarded the North Carolina Community College System’s “Excellence in Teaching” distinction. The recognition identified him as an educator who exemplifies the highest quality and standards of instruction. His passion is evident when he talks about the craft and sharing it with others. He loves being able to teach these skills to others and has experienced first hand how welding can change a person’s life.

Learn more about faculty pay

A path to welding

Dixon was around 10 years old and helping his uncle when his interest in welding began. His uncle worked a factory job during the week, but on the weekends, he did mechanical repair, tractor implementation, farm equipment repair, and so forth. This was in the mid ’80s when there was a heating and oil crisis, so he also did a lot of welding and cutting to build wood stoves.

“That’s what got me started, helping him,” Dixon said.

After high school, Dixon started working in maintenance at Container Corporation of America, the same company his uncle had worked for. He, like his uncle, continued to weld on the weekends.

In 1993, Dixon became paralyzed in a motorcycle accident. Afterwards, he went back to school and received a degree in occupational technology which is based in computer information systems. Although he had switched careers, he realized he didn’t want to sit behind a computer all day, so he relied on his memories and love of welding to guide him back to school.

Dixon enrolled at Forsyth Technical Community College and had a great mentor in Rob Smith. After receiving his welding diploma in 2006, he started teaching part-time, and eventually it formed into a full-time position. He stayed at Forsyth Tech for seven years. He has since worked at Surry Community College and is now at Davidson County Community College, teaching and expanding the college’s welding programs.

At Surry Community College, Dixon grew the welding program from 12 to 100 students. He successfully wrote and received a grant from the American Welding Society’s Welder Workforce to put a new piece of machinery in their now state-of-art facility. He started working at Davidson County Community College in 2019, and has now been teaching for 14 years in the community college system.

Community college system

Reflecting on how the general public sometimes undervalues the community college system, Dixon believes he and his fellow citizens are lucky to be in close proximity to quality education.

“It is such a valuable and needed institution in every community that we serve,” he says. In Yadkin County alone, he is 45 minutes away from five different community colleges.

And while Dixon acknowledges that four-year institutions are valuable, he believes community colleges are just as important. In his mind, both entities are on the same team and should “play on the same field.”

For some students, in the “field” of higher education, community college is the better option.

“Those students that it [a four-year university] doesn’t work for, they’re very teachable. While they may not be suited for the four-year system … community college may be their saving grace in that now they’re going to gain a degree or diploma or certificate that’s going to allow them to to get out of whatever economic disparities they may be in,” Dixon said.

Dixon says in many rural communities, his students’ parents worked in textile mills, and those jobs have disappeared. In those careers, wages may have been capped at around $15 per hour. It is exciting for those families to see what their children, Dixon’s students, can earn after receiving a one-year diploma in welding.

“We need educated individuals to run these sophisticated robotics [and] the CNC operated machinery. Its becoming much more a technical field than it is, you know, the guy back there in the dark, dirty, nasty room with the hammers and the anvil. So I think we’ve got to change the image and perception of our industry. And I think that’s happening,” he said.

Dixon says he can’t go to a grocery store within three counties without someone coming up to talk to him. It’s either a former student or a family member of someone he has taught, and he loves it. His connection to his craft and students is undeniable.

“You know, my life with being paralyzed now, I won’t call it a daily struggle, but it does present issues that I have to fight to overcome to get to work every day and be there for those students, and I think it makes them push a little harder,” said Dixon. “They see that, you know, I overcame what I had to deal with just to get there that day. And I’m there, and I’m there to help. And I think it gives them a little bit more of you know, ‘if he can do it, I can do it. And I want to do well for him.’”

Recommended reading