|

|

It’s dark when Tori Hunt rolls out of bed. She’s on a ship in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and it’s 4 a.m., so she’s moving slowly. She hasn’t had a full night’s sleep in weeks – instead, she squeezes in naps from 30 minutes to a few hours long every now and then.

“Science never sleeps,” Hunt said.

Hunt – a former earth and environmental science and physical science teacher at Concord High School in Cabarrus County– spent the entire month of September aboard Exploration Vessel Nautilus (E/V Nautilus). As a science communication fellow, Hunt joined the E/V Nautilus on its expedition within Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, one of the world’s largest marine protected space places.

From a young age, Hunt took an interest in marine biology, particularly sharks. But when she took chemistry in high school, she “fell in love” with the subject and decided there was so much more she wanted to learn. She ended up at Appalachian State University, where she studied chemistry with a concentration in secondary education.

“I fell in love with education and thinking about how to get people excited about science,” Hunt said.

By the time she began teaching high school science, Hunt said she’d pretty much set aside pursuing her interests in the ocean and ocean exploration. But, when an advertisement for the Ocean Exploration Trust Science Communication Fellowship came across her Facebook, Hunt took it as a sign.

Hunt was one of 16 science communication fellows who participated in various expeditions aboard E/V Nautilus. Hunt’s expedition visited Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, a part of the sacred waters and ancestral islands of Kānaka ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiians).

Hunt, a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, said that participating in an expedition that centered and incorporated Indigenous knowledge and culture felt significant.

“I feel so incredibly lucky that this was the expedition that I got to participate in, not only because of where we were going but the people that I got to sail with, as an Indigenous woman,” Hunt said. “It felt so, so special to be sailing with all of the Kānaka ʻŌiwi – the Native Hawaiians – on board.”

Aboard the ship, Hunt “sat watch” from 4 a.m. to 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. every day as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) mapped and gathered data. ROVs are sent to the sea floor with cameras and lights, and then scientists can see rocks, coral, sponges, fish, and anything else on the sea floor. Hunt said that often, this is the first time anyone’s seen some of these organisms.

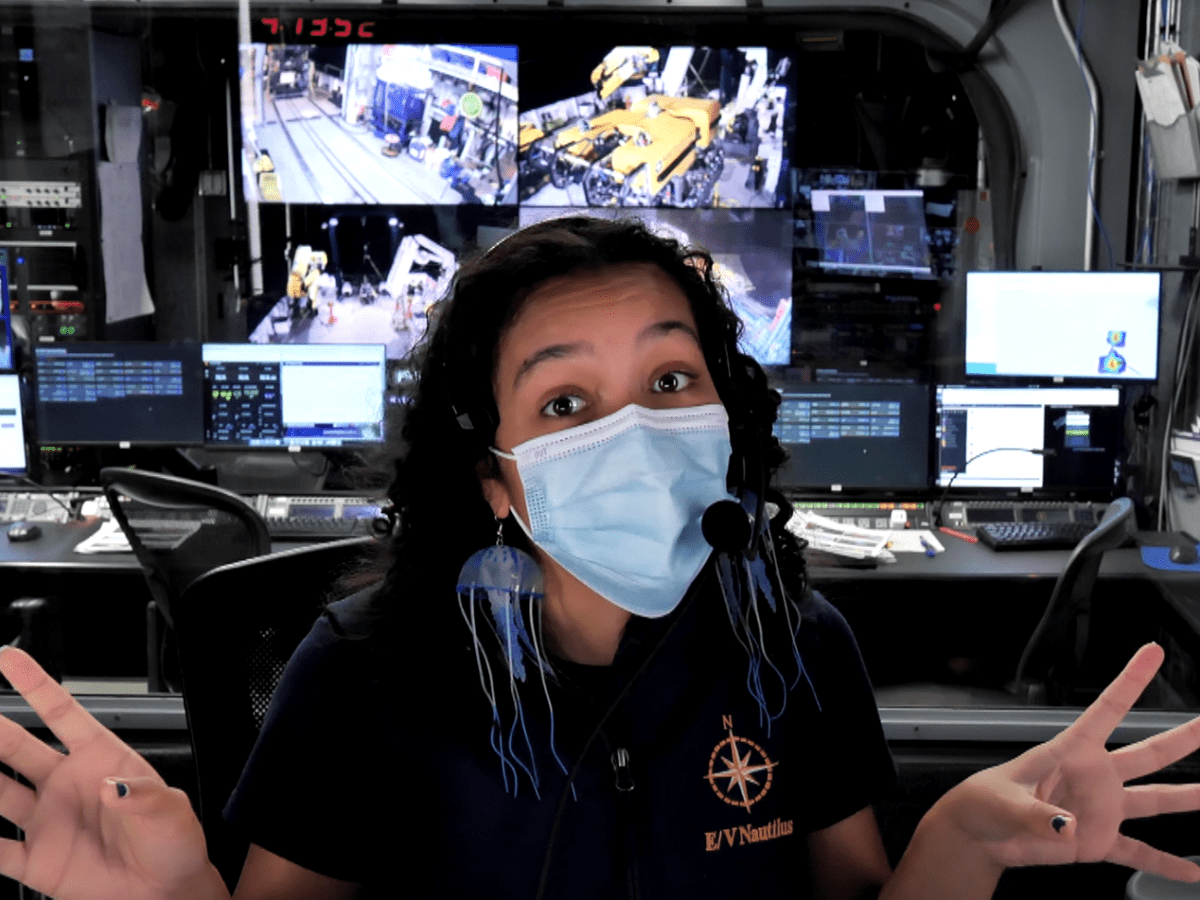

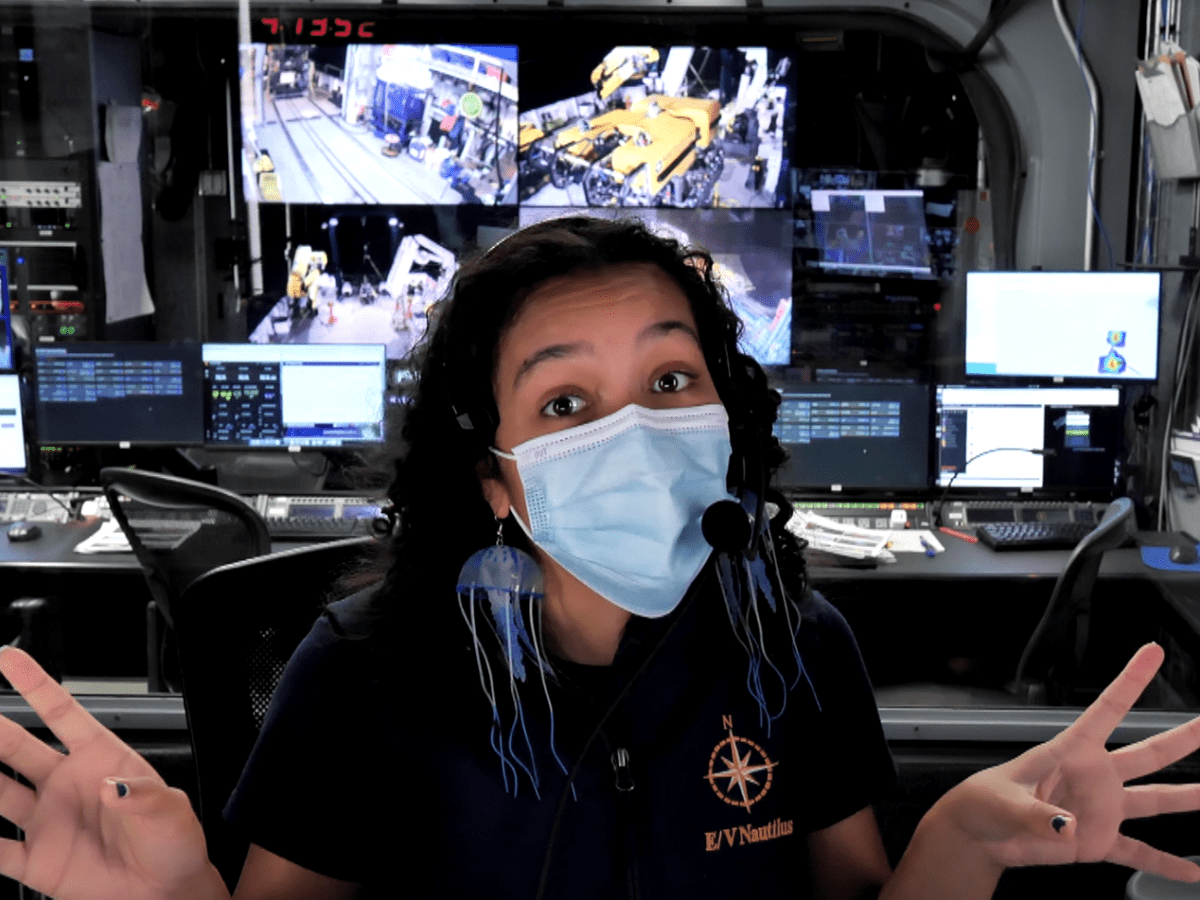

On a typical watch shift, she’d sit in the control van, monitor the chat, and participate in dialogue with users watching the E/V Nautilus’ 24/7 live stream.

Hunt recalled one of her favorite dives where the team encountered a dumbo octopus.

“As a science teacher, it’s really, really, really fun to be able to bring just the ocean and all parts of the ocean that are mysterious, all parts of the ocean that are unknown, to just a huge broad audience and get people excited and curious and asking questions,” Hunt said.

Another of her main tasks as a science communication fellow was to host “ship-to-shore” interactions. These are 30-minute one-on-one interactions when teachers and students from anywhere in the world sign up to learn about the expedition through virtual meetings with Hunt and other fellows.

“My job is to kind of be the bridge between the outside world that’s viewing and inside our control van where like the science conversations are happening, where the operational conversations are happening,” Hunt said.

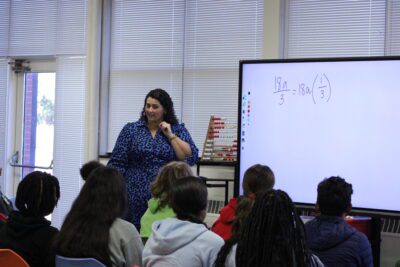

Hunt said this is when her experience as an educator became vital. In her classroom, Hunt often makes science and scientific language understandable for her students. In these ship-to-shore interactions and livestream chats, this is exactly what Hunt did.

In her four weeks aboard the ship, Hunt and two of her colleagues broke the record for the number of ship-to-shore interactions – hosting more than 170 with students from all over. She also hosted one ship-to-shore interaction with each of her classes back in North Carolina and one interaction for her entire school.

There’s a five-hour difference between North Carolina and Hawaii, so being able to hop on a ship-to-shore interaction with her students in North Carolina meant Hunt had to start her day at 2 a.m.

“Whoever wanted time and space to talk with us, we would make it happen,” Hunt said.

Aboard E/V Nautilus, Hunt maintained contact with her students outside of the ship-to-shore interactions – posting highlight videos and other assignments to Canvas. Students often logged into the ship’s livestream as well. She credits her colleagues back in Concord for their support in her classroom while she was at sea.

After the expedition, Hunt was tasked with creating a deliverable that educators could access free of charge to teach about the sea and deep sea exploration in general. Hunt said that deep sea exploration isn’t just science – there’s interdisciplinary work going on aboard the ship. This is evident in the resources provided to educators.

“It wasn’t just the science,” Hunt said. “There’s art, there’s humanities, there’s math, there’s engineering, there’s hands-on activities, whole unit lesson plans, digital graphics, like animations, like all kinds of things.”

That interdisciplinary spirit was a major part of the expedition. The location of World War II’s Battle of Midway lies within the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and part of the expedition explored this site. Japanese and American archaeologists joined the E/V Nautilus via livestream to help determine what they were looking at and to learn more.

“To kind of have an example of what happens when you bring people together from different backgrounds, different point of views, different experiences – that is when the work is so rich and so beneficial,” Hunt said.

Hunt took every opportunity she could to learn about each role on the ship. From mappers and navigators to engineers and scientists, Hunt learned lessons of her own.

“I pretty much tried to get my hands on everything that I could,” she said. “I was kind of all over the ship, just learning about all of the different roles and responsibilities.”

When she returned, Hunt took her experiences back into her classroom and school in the hopes of “(opening) their eyes to possibilities for their futures.” She spotlighted her crewmate and their careers at the start of each class and incorporated mini lessons on Hawaiian language and the cultural relevance of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. She hopes that what she’s learned will help broaden her students’ perspectives about the world and science.

Her month aboard E/V Nautilus sparked a new passion in Hunt — one for ocean exploration and science communication. Last fall, Hunt made the “difficult decision” to transition out of the classroom. But, she’ll pursue more opportunities in science communication and science education and outreach.