Share this story

- West Edgecombe Middle School implemented lessons they learned from their microschool in a macro-way. Learn more about how they partner with students in their learning here.

- "Feedback is a gift." Find out how West Edgecombe Middle School uses collaboration to pilot innovation and progress for their students.

|

|

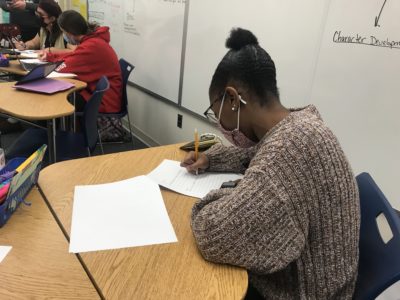

Laura Moss wants to be a psychologist. She is in the eighth grade and lives with her mother, who she says is having a hard time right now, in Edgecombe County. She says she wants to be able to support both her and her autistic brother in the future.

When asked what inspiration West Edgecombe Middle School has sparked for her, she and her peers on the panel give an unpopular opinion.

Math.

Moss said she was not always that great at math.

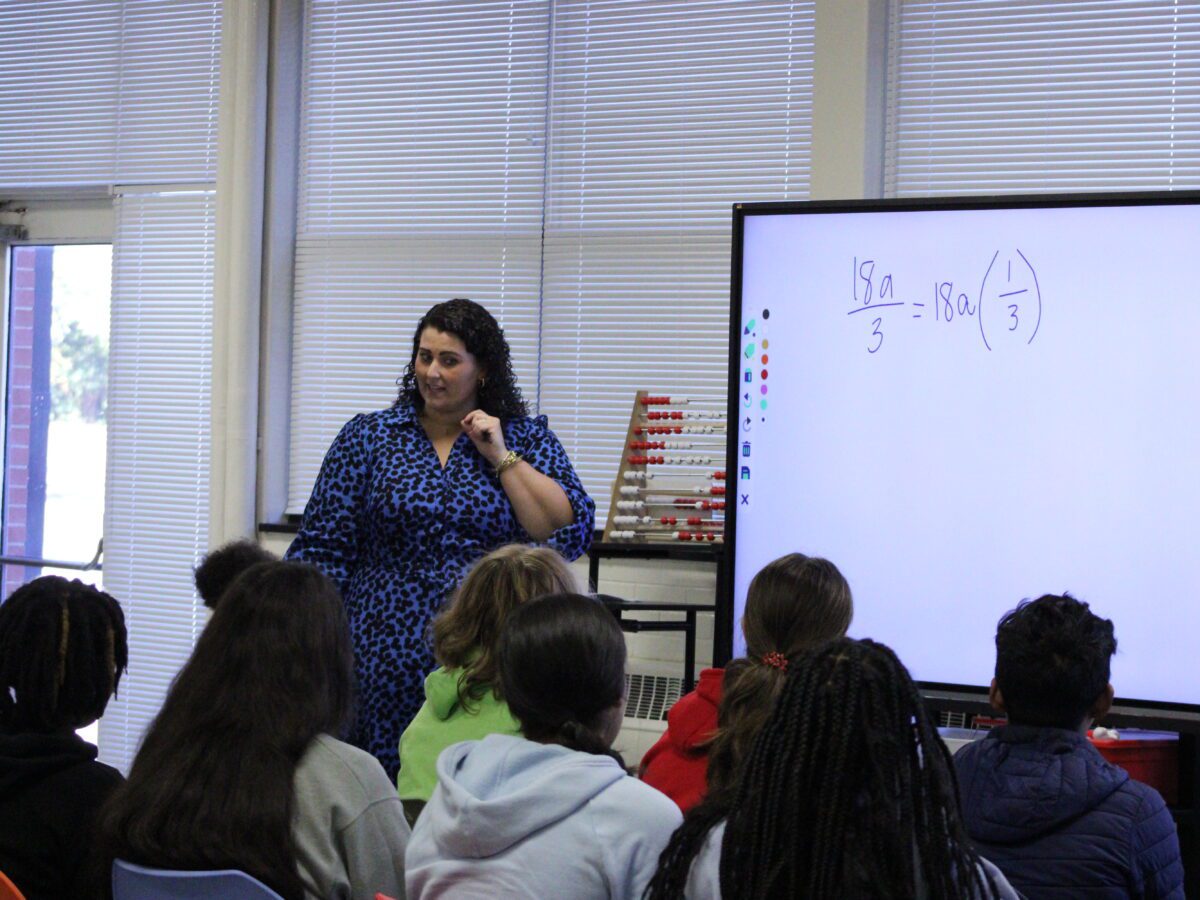

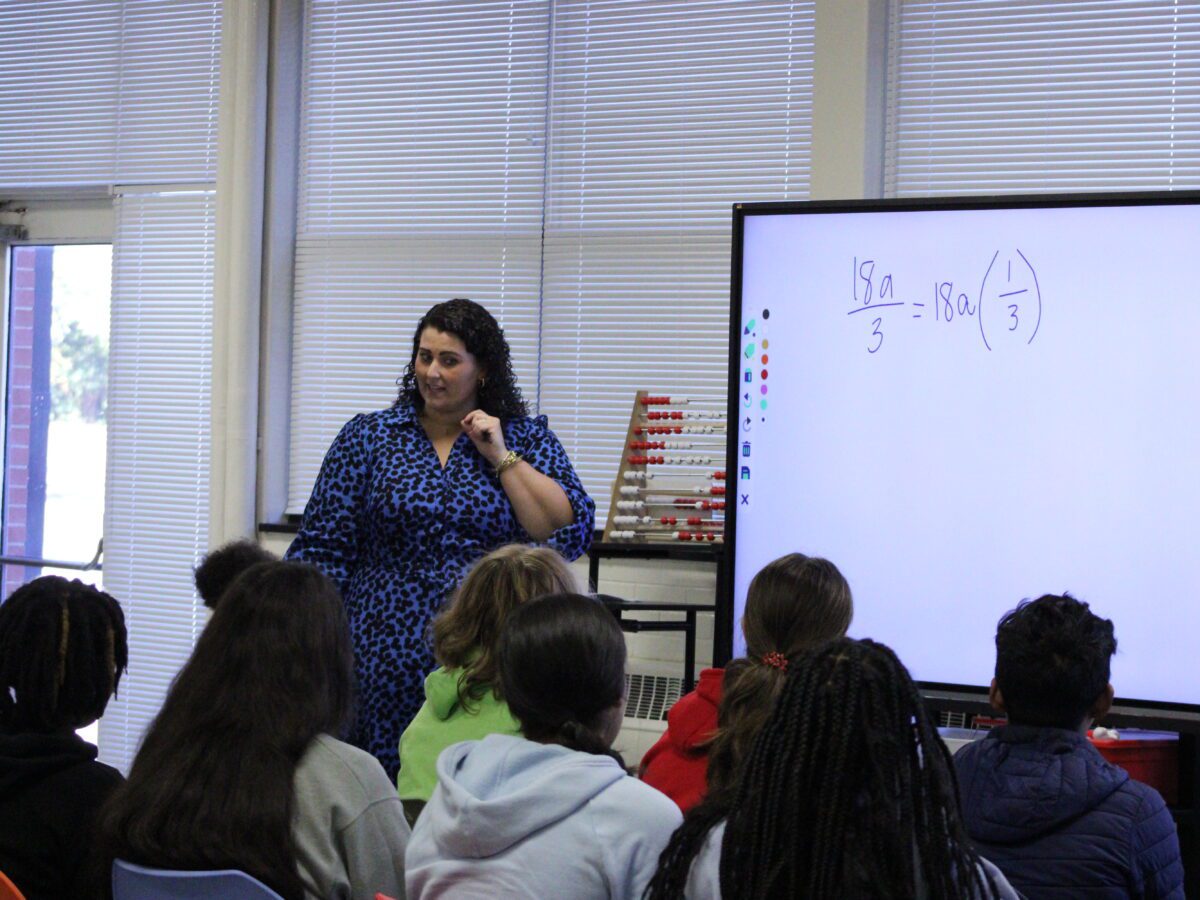

“I didn’t understand it. I just kind of memorized it when I got into Dr. Ballard, where she helped me actually know how to do the math and not just memorize algorithms and stuff like that,” Moss said. “So her class definitely made me more interested in math than I was before.”

Dr. Kelsey Ballard is the school principal. But she also teaches Math I to the eighth grade class — a course meant for high school students in North Carolina. She decided to lead the course as a way to keep West Edgecombe on the growth path.

“Throughout the years, we either met or exceeded growth. 2022 was the only place that we only met growth, but we did it once again in 2023,” Assistant Principal Evan Parrish said. “So at this point in time as well, we should have elevated our status as a school and got out of that low-performing area to be a ‘C’ school.”

According to the North Carolina School Report Cards, West Edgecombe Middle School hasn’t had a performance higher than a “D” level since before the pandemic. However, this year they exceeded their academic growth goal at a 90.9 percent rate — the highest compared to other schools serving the same grade levels in Edgecombe County Public Schools.

The peak in performance is attributed to the ways they’ve redesigned the school experience.

They started small. They spent time conducting research and interviews among students, parents, and the Edgecombe community to understand what was and wasn’t working about how the school day was designed. Once they launched the Imagine West Microschool in the 2020-21 school year, they prioritized communication with parents and supporting staff within the school.

Microshool became popular during the pandemic because it consists of a small group of students — normally 15 or less — working with one teacher.

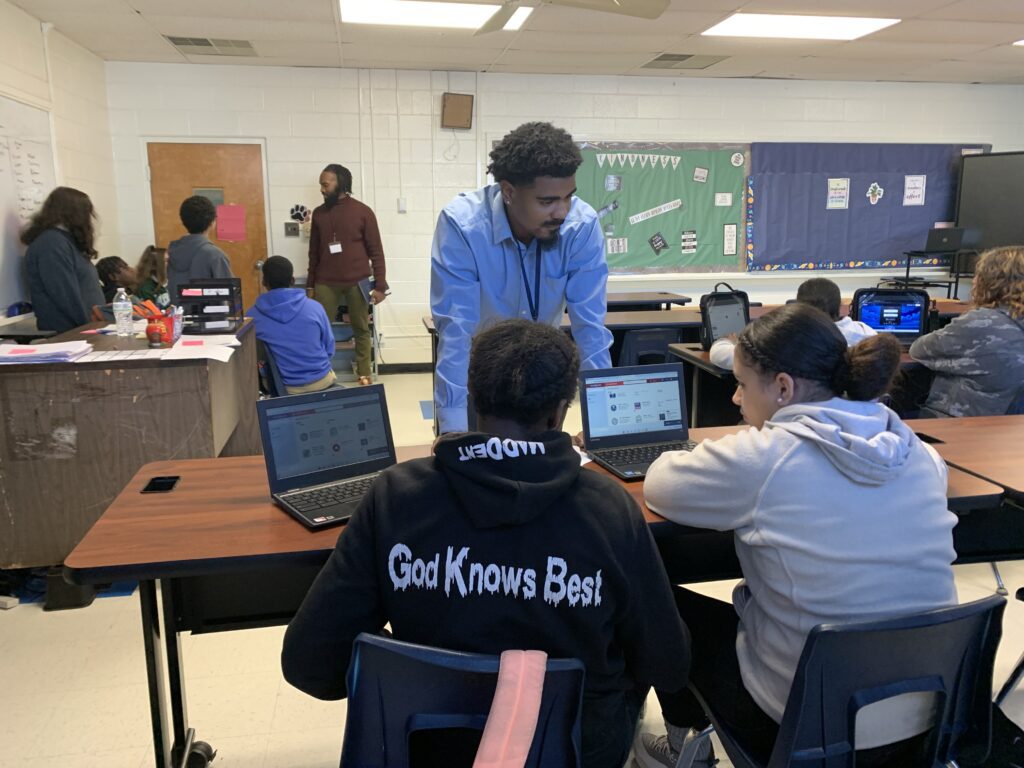

The school schedules of students in the microschool are tailored more to their interests in comparison to traditional classroom settings. They have flexible classroom seating and an open floor design concept so they can interact more with each other and have free flowing communication with the teacher. Teachers are up and about, managing supplies and taking questions from each student group, and they spend a minimal amount of time in the front of the room lecturing from the projector screen.

Parrish said that both students and adults connected to the school thrive off of structure, and they appreciate the school’s commitment to follow up after they express concerns.

“Those relationships that you have with those students and with the resources that you have in the building, meaning of those people that you have in the building — those are the most important relationships that you have,” Parrish said. “Every person in the building is truly a relationship that you need to find and cultivate in order for you to understand that person.”

The pilot consisted of a group of sixth graders who received core instruction in English and Math.

Out of the macro changes that came from microschools came Learning Hub and Spokes. Now offered to the whole school and not just a select group of students, these courses were developed to teach students real-world applications.

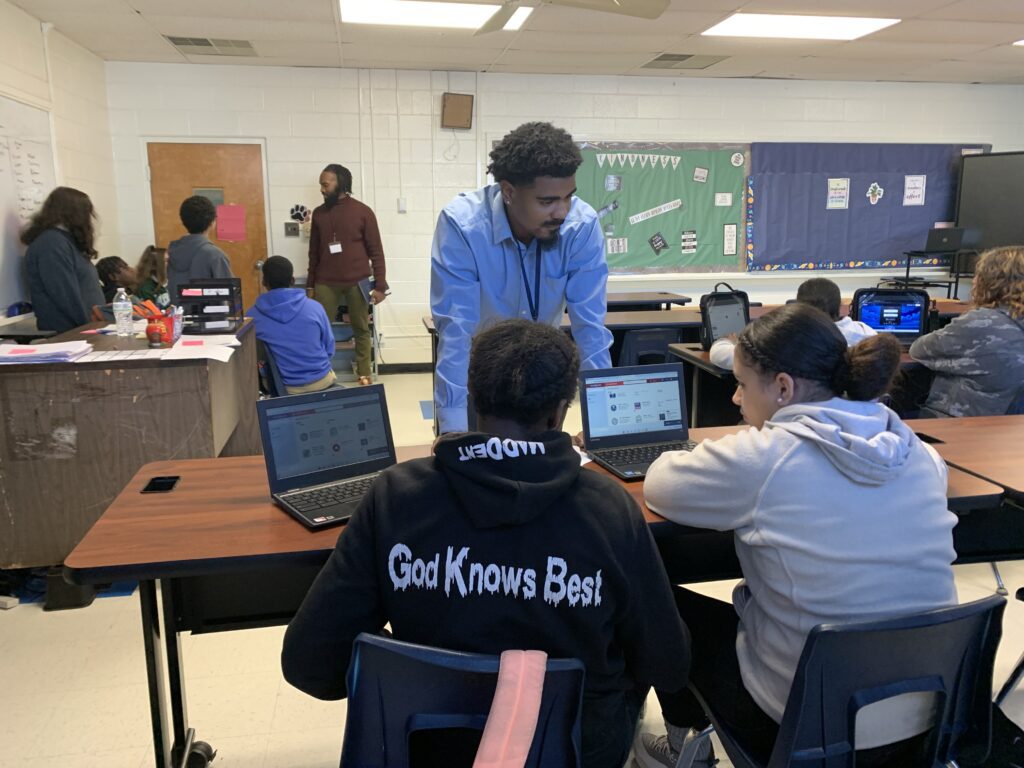

Terrence Whidbee is a first-year teacher and facilitator of the course for all grade levels. He sees his job as not just getting students to memorize data, but to apply what they learn from other core classes.

“What kind of question can we develop to say, hey, my community is over-polluted, my community’s having pollution problems, or my communities having waste problems, and I want to solve this issue. So what are some questions that we can use to develop it? “ Whidbee said.

The curriculum was developed by Design for Change; experts wrote it based on a global initiative to help students be more aware of the world around them. The class is tasked with collecting data and interviewing experts about their projects to present to the class at the end of the term.

Throughout the planning and development process of their goal, students work with their peers to get feedback. The classroom is lined with a wide table for open seating and room to fill out papers and work on Chromebooks. The teacher moves not as the centered fixture. but floats between groups to directly advise students about the direction they are going.

Timothy O’Shea, the school’s academic climate and family engagement specialist, emphasized how the course was key to the school redesign process.

“Some students are like, ‘This is too much work. Why are they making me do this?’ But then others are starting to learn and reason and understand that, they’re letting me do this because I have a say now — I have an agency in what I’m doing and owning my learning,” O’Shea said.

Mostly, students are embracing the freedom it gives them compared to other classes with a traditional structure.

“Since this class is spokes, it’s more of like, asking you what you want to do in life, how you can do it. So it’s not really a career development class but more open minded and expressing what you’re trying to do,” Sean Whitehead, a seventh grade student at West Edgecombe, said.

Other ways that the school has tried to empower the students have been logistical. They have increased exposure to more STEM activities. They also have two teachers delivering math instruction at a time — the school’s weakest testing area. They manage class schedules so that the halls are quiet when the material is being delivered and collaborate with different community outlets.

Teachers are also expecting and welcoming of observation in their classroom from other school staff and outside visitors. From O’Shea’s perspective, when teachers visit their peers they make sure to “continually say feedback is a gift.”

As students matriculate, they express the desire to be seen and listened to.

“One thing I would say you should add to this course is advocating for different learning styles because not everybody learns the same way. In some classes I was in, all you would do was just watch the teacher teach. (You) wouldn’t actually get to do the work or what it would look like on a test, and you wouldn’t really know how to do it because all you were doing was watching,” Moss said.

As they progress to their goals and receive feedback, Ballard said that embracing change is key.

“We realized that change is coming. Change happens every day. And so we needed to embrace that,” Ballard said. “But we also wanted to make sure that any changes that we had the power to control here at the school level, that we were leveraging the voices of our students.”