|

|

Debbie Keyes and Ginger Hardison run the only two home-based licensed child care programs in Washington County — and they have a combined 43 years of experience doing it.

In North Carolina, licensed child care programs can be based in either centers or homes. Home-based programs are referred to as “family child care homes,” or FCCHs. They make up 21% of licensed child care enrollment in the state.

While the number of FCCHs in North Carolina has decreased by one-third since 2018, Keyes and Hardison have been steadfast in their commitment to providing affordable, accessible, high-quality care and education to young children.

According to a 2022 report on the importance of expanding home-based child care in North Carolina, families choose FCCHs — especially for infants and toddlers — “because it is often close to home, affordable, flexible, and can foster a child care environment that shares the family’s cultural norms and values.”

Each of these factors is especially important in rural, majority-Black counties like Washington.

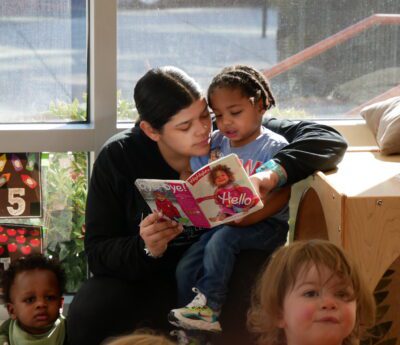

‘A home away from home’

Debbie Keyes’s family child care home is on Backwoods Road in Roper, next door to the house she lived in growing up, and not far from where she was born. She has lived in Roper for all of her 48 years.

“I just love the quietness of it,” Keyes said. “It just feels homey.”

She has operated Blessing Children Family Child Care from her home since 2010.

Before that she worked for a boat manufacturer in the area. But she says she had always “kept kids” on the side.

Experts refer to that type of child care as “friend, family, and neighbor” (FFN), or “kin care.”

When Keyes lost her job at the boat manufacturer in the Great Recession, she decided to start her own licensed child care program.

The Tyrrell-Washington Partnership for Children — the county’s local Smart Start office — helped her find the right classes at Martin Community College and College of the Albemarle to get her certification.

Blessing Children Family Child Care is a 3-star licensed FCCH, currently serving four students from birth to age 5. The families of all four children use the state subsidy program to help pay tuition.

“I wish there was more, money-wise,” Keyes said of the subsidy amount. “Once the bills are paid, I don’t really have a salary.”

That’s why the stabilization grants offered by the state during the pandemic were so helpful to many home-based educators like Keyes. She said she was able to buy “toys that won’t break” and give herself a “bonus” — what most people would consider a salary — with those funds.

The federal funding that supported those stabilization grants expired in September 2023, but North Carolina has managed to stretch its funds through the end of June 2024. At that point, Keyes will go back to not having a salary.

“It’s gonna hurt, it’s gonna be really hard,” Keyes said. “That’s why I’ve been praying they’re gonna figure out a way to keep it going.”

While Keyes acknowledges that continuing stabilization funds or increased subsidy payments “would make it a lot easier,” she also says her reward is getting to see one of the babies she cared for run up to see her when she goes to pick up her 13-year-old son at the end of the school day.

Despite the financial hardships of being a home-based educator (which are offset by her husband’s income), Keyes loves her work.

“Kids are drawn to me,” Keyes said. “I could be anywhere and a little baby could be crying and I’ll say, ‘Let me see ’em,’ and they’ll calm right down.”

It’s that kind of comfort that Keyes points to as the reason families choose home-based care: “It just feels like a home away from home.”

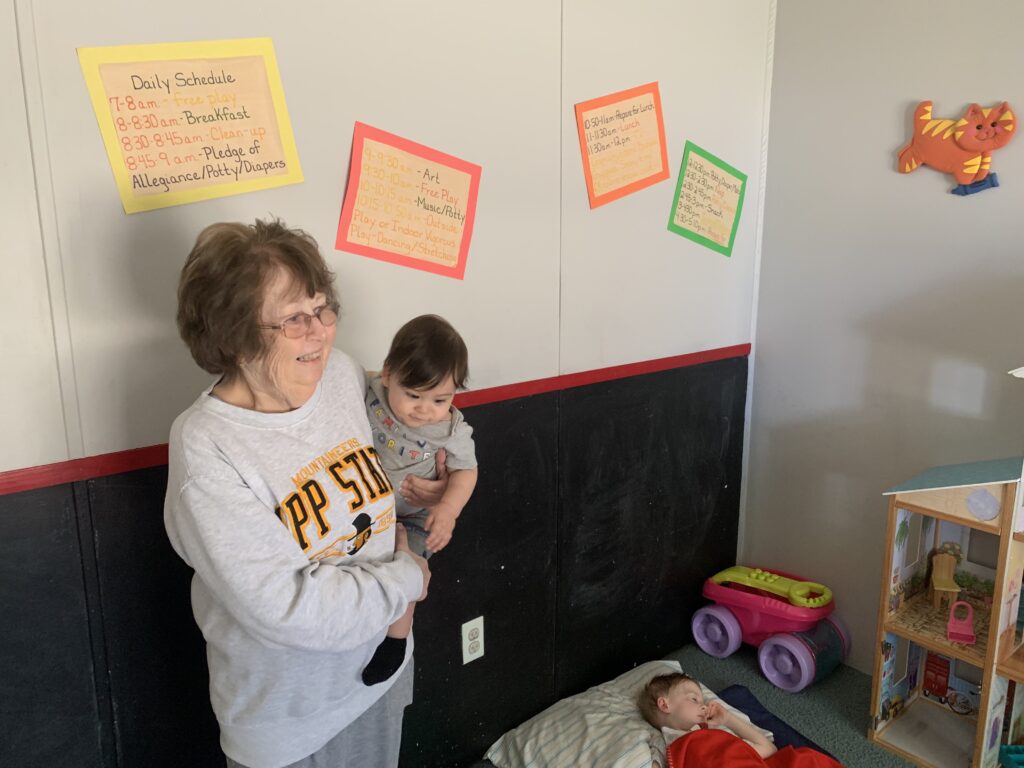

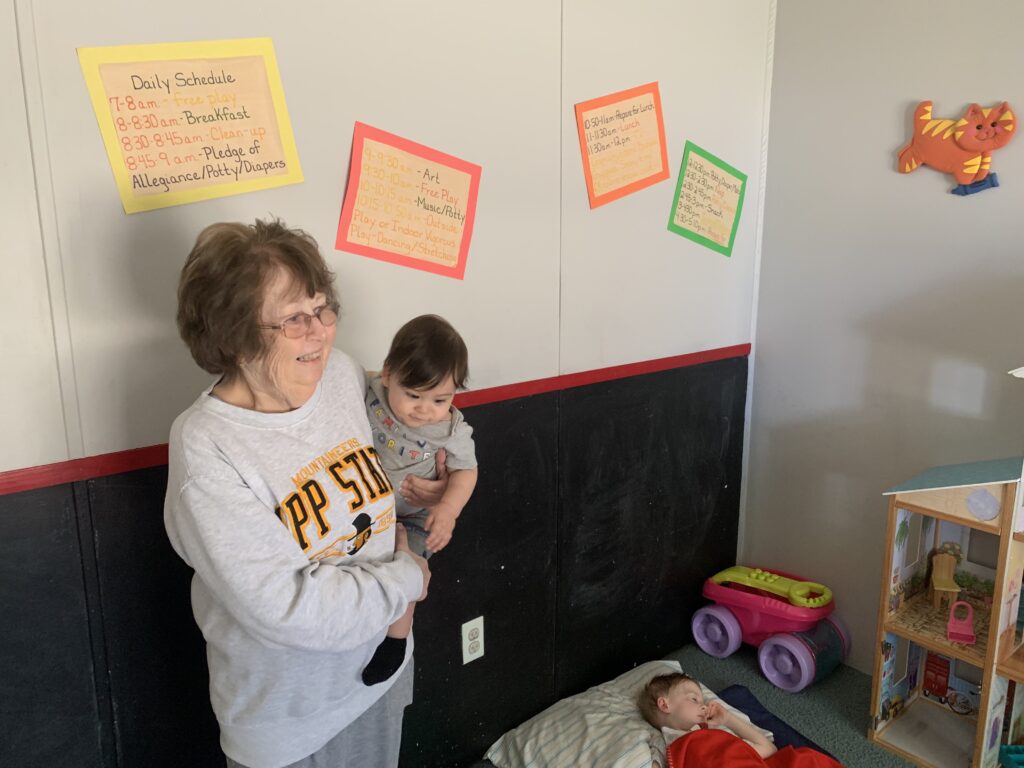

‘Whatever they throw at me’

Like Keyes, Ginger Hardison has lived in Washington County her entire life — for 73 years. She will have been operating Ginger’s Day Care Home from her house in Plymouth for 29 years when the stabilization funds expire this summer.

She has five students between birth and age 5 enrolled, plus three who come in after school some days.

“I still have a little girl that will be 15 in September, I got her when she was 11 months old,” Hardison said. “She still stops by maybe an afternoon or two a week. And I took care of her mom!”

Hardison’s career in early childhood education began like Keyes’s did — she “kept kids” at her home, providing FFN or kin care to neighborhood children while their parents worked.

“And then, later on down the line, one of my friends built a daycare, and she come and asked me if I would fill in for them,” Hardison said.

That was the beginning of her 25-year career in center-based early childhood education.

But the center closed its doors when the county began offering school-based public preschool, so Hardison decided to open her own FCCH.

She got the credentials she needed from Beaufort County Community College, and now Ginger’s Day Care Home is a 2-star licensed FCCH with deep roots in the community.

After 54 years of caring for children, Hardison has earned some perks.

She never has to pay for her meals at a local sandwich shop because she took care of the girl who works there for five years.

And Hardison said that because she took care of the families of her dentist and hygienist, she never has to wait for appointments.

“It’s a nice perk,” Hardison said, because, “Right now, the cost of everything, oh my goodness, is astronomical.”

The stabilization grants have helped offset some of the specific costs associated with operating a FCCH.

“I didn’t get, you know, a whole lot, because I’m a family child care home,” Hardison said.

But she used what she got to provide some students with “scholarships” for several months, allowing them to remain in her care when they otherwise may not have been able to afford it.

Like Keyes, she also used her stabilization grants to upgrade toys and buy groceries. And when the grants end this summer, she has her husband’s retirement income to help her fill any financial gaps.

“Whatever they throw at me, I’m gonna do my best,” Hardison said.

Keyes expressed a similar determination: “Money or no money, I still have to give what all I can give to the kids.”