|

|

Behind the Story

This is the fifth piece from “School’s not out,” a series of stories from the road this summer about child care providers and the communities that rely on them in every season. In the absence of national and state investments, local leaders are stepping up to work toward solutions to the child care crisis. Meanwhile, federal relief funds are running out at the end of this year, leaving many programs with tough decisions and families with even fewer affordable child care options. Subscribe to Early Bird to follow along as EdNC documents this particularly fragile moment in early care and education. Go here for past stories in the series.

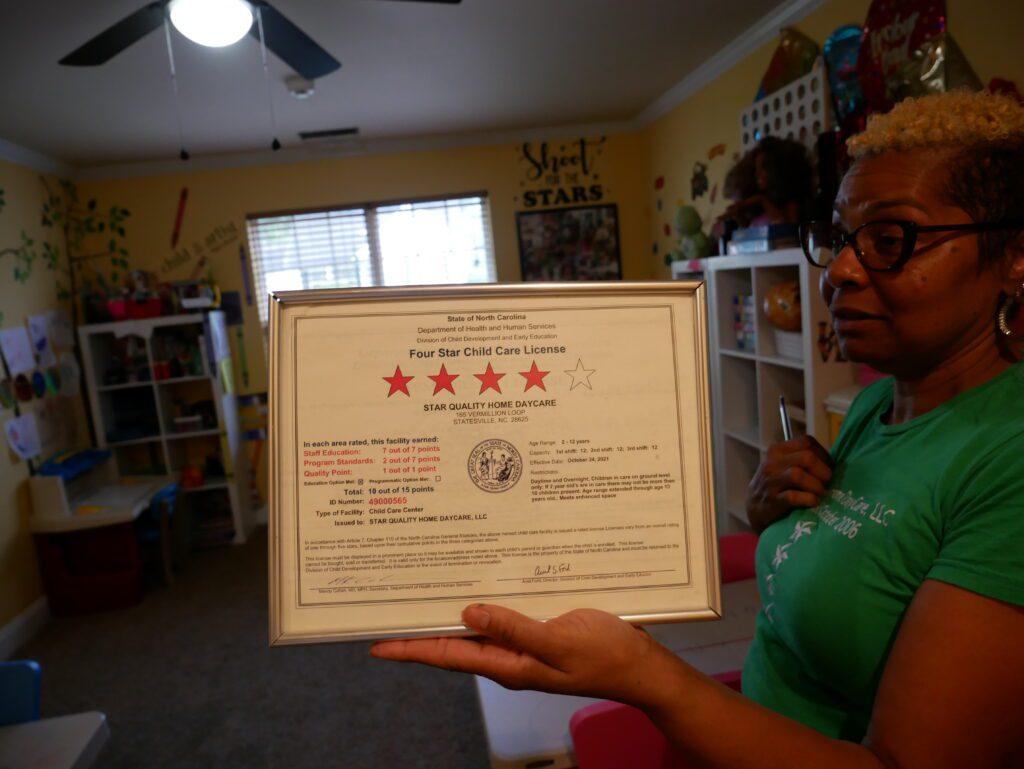

Angela Imes, known by her students at Star Quality Home Daycare in Statesville as TiTi, pointed to a wall of photographs of children she has taught.

“He’s going to school to be an attorney,” Imes said. “He’s about to graduate; he got a scholarship for football. She’s going in real estate. She’s going to major in chemistry and minor in biology.”

Imes, who opened her family child care home in 2006, is one of almost 1,200 licensed family providers for small groups of children across the state.

Home-based providers often have particularly personal, long-lasting relationships with children and families. Those strong ties were especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when homes stayed open at higher rates than other early childhood settings.

“If it had not been for them during COVID, we would have been in dire straits in this state,” said Tammy Barnes, assistant director of the regulatory services section in the Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE).

Family child care homes play a key role for families who want intimate settings and more flexible and affordable care. Research says they are more likely than larger child care centers to serve Black and brown and rural communities.

But North Carolina has 30% fewer licensed homes than in 2018, when a little more than 1,700 homes were operating. A couple of years before, there were close to 5,000 homes, Barnes said.

The state also has fewer children in home-based settings than other states with similar populations, according to a 2022 report on home-based care from Stoney Associates.

Now, as the state heads toward a fiscal cliff for child care, state officials are turning their attention toward strengthening family child care homes. In interviews with EdNC, providers such as Imes said shortages of funding, technical assistance to meet licensing requirements, and respect were creating barriers to serving children.

“Just because we are choosing to work from our homes, that doesn’t mean we’re doing anything less,” Imes said, speaking of her work in relation to center and school-based early care and education. “We just have a small amount of children.

“We should have more funding and support because a lot of us do serve poor children and families — and it takes money to do that.”

‘Doing the same thing’

Imes recently went through a months-long process for her site to become a “center in residence,” another category of licensure that allows her to get more funding from the state’s subsidy program and serve more children.

That process opened her eyes to the funding disparities among different settings. She used to receive $600 a month per 2-year-old, she said. Since earning the new status, she started receiving the same rates as centers, which meant $900 a month per 2-year-old.

Before an interview with EdNC in July, Imes spoke to six other family child care providers in Iredell County. She said they had questions: “What is the reason centers and homes have different pay rates from subsidy when a lot of us have the same if not more education, star ratings, and are doing the same thing?” Imes read from a piece of notebook paper.

Child care subsidy rates are based on market surveys in which providers report what they charge parents privately. Yet experts say the rates do not reflect the true cost of care. And parents often have copays they struggle to pay. Many parents who are ineligible for vouchers still cannot afford care.

“In the 21st century, we should have the capacity to have more realistic rates based on what’s really happening and what the real costs are,” said Magda Baligh, executive director of the Warren-Halifax Smart Start Partnership for Children.

The state is studying how to set rates based on the true cost of care rather than the reported market rates. Though results from that research are not yet public, DCDEE Director Ariel Ford said the cost differences between home- and center-based care are not as large as the rates reflect.

“It is less different than what our current subsidy rates would indicate,” Ford told EdNC.

‘I didn’t want to inconvenience the parents’

The family environment of home-based care comes with large sacrifices for providers, many of whom perceive their programs not as businesses, but as necessary community services.

Angela Somerville, owner and director of Stay and Play Child Care in Warren County, charges parents less than the market rate. She raised her private rates this year for the first time since 2016, but decided she would not charge existing parents more.

“I always tell my parents, when you bring your children in, they’re my children,” Somerville said. “When you all come in, you’re also my children.”

That same mindset meant that for 21 years, Somerville did not take a vacation other than two days at Christmas.

“Parents have to work, so why should I take a day off?” she said. “I was just open because I didn’t want to inconvenience the parents.”

Whenever possible, Imes provides scholarships and reduced rates to parents. But children’s needs have to be paid for somehow, she said. That not only includes learning materials, food, and a teacher’s salary, but countless other expenses.

“Parents can’t afford to buy underwear sometimes,” she said. “Parents can’t afford to have decent socks sometimes. So when (the children) come to Star Quality, guess what? They have underwear. They have pants. I go to Walmart or wherever and I bring them home, wash them up, iron them, and they have clothes.”

Without the business structure to support those needs, Imes said, some local programs have started to operate without licensure to serve more children than allowed under the state’s rules.

“Providers are not getting enough money, so a lot of them are closing their doors and providing care for children unlicensed, and making more money … And it’s not fair to us that are going by the book,” she said.

‘Building capacity again’

More regulation in recent years — without an increase in the funding Imes and Somerville said is necessary — is one factor contributing to the decline in sites, Barnes and Ford said. In 2016, homes had to start meeting the same health and safety requirements as centers because of a change in federal rules. That led to a decline in the number of homes before the pandemic, Barnes said.

“It was declining anyway, a lot because of the new rules that were in place with health and safety,” she said. “And a lot of people that were just saying they couldn’t make any money off of it.”

Although health and safety requirements were needed, Barnes said, there is a need for technical assistance to help providers through the process of licensure and compliance. The state is contracting with Southwestern Child Development Commission on a technical assistance project focused on family child care homes.

“We’re going to try to start building capacity again with our family child care providers across the state, hoping to bring more people on board, helping them understand the rules better and the business aspect and how to get in it from the very beginning,” Barnes said.

The state is also reviewing its quality rating and improvement system (QRIS), which is how schools, centers, and homes are rated on a scale from one to five stars. Programs must have at least three stars to participate in the subsidy program.

In Robeson County, Towana Neal has spent the past year navigating licensure, QRIS, and subsidy. She took the required workshop and communicated with a state consultant to get her ducks in a row. She started serving eight children, most of whom were receiving subsidy vouchers, when she opened WanaPooh Daycare in January with a provisional license. She hired Barbara Harris, who has been in child care for 16 years, as her teacher.

Yet Neal said she did not know about the education requirements necessary for subsidy participation. By June, Neal’s program was reduced to one star, meaning five of the families she was serving no longer had care arrangements.

“Some don’t want to take them to nobody else but me,” Neal said. “They’re like, OK, I’m gonna wait until we see what happens.”

Neal said she is willing to go back to school if it means saving her program, though she is unsure how she will pay for it. She said she is using dwindling stabilization grants and her spouse’s personal funds to pay Harris’ salary, and is not paying herself. She is serving three children through private tuition. She and Barbara are willing three stars back into existence.

“Our kids are our lives,” Neal said. She pointed to a wall in her home. “This is our motto right here: The future of the world is in this room.”

The 2022 report said some of the licensing and subsidy requirements should be reconsidered.

“In short, limiting opportunities to participate in child care quality improvement supports or resources potentially hurts thousands of North Carolina children and families,” the report reads. “A broader, more flexible approach to quality improvement could focus on enabling a range of safe child care options that support child development in homes, faith-based and community settings.”

Both when it comes to establishing new programs and sustaining existing ones, the report says that culturally relevant technical assistance, funding that is not tied to star ratings, and the establishment of peer networks of support are needed, both for licensed and unlicensed programs.

“The state cannot afford to lose a critical source of child care,” the report reads.

Recommended reading