This is the second article in a series on the transfer experiences of North Carolina’s students between community colleges and four-year institutions. Click here to read the rest of the series.

Matt Wright is an entrepreneur. He’s also a student at North Carolina State University, where he transferred after attending Central Carolina Community College.

Wright started a business as a fitness and basketball trainer. His goal is to build a career as a basketball coach, an avenue, he said, for working with and mentoring kids. Toward that end, he runs his business every Friday teaching kids how to play the game, and he volunteers another 15 hours a week coaching a middle school basketball team.

Teaching basketball, as a trainer and a coach, is straightforward professional development for Wright’s career goals. He’s racking up relevant experience. But how does that translate to academics?

Wright knows the math. Bachelor’s degree holders earn more money over their lifetimes and have more economic opportunity than people who stop with a high school diploma or associate degree. He’s pursuing a bachelor’s as a tool to advance his business and fuel his economic opportunities.

The question facing Wright — how to make his education serve his economic ambition — is also one the state faces. In 2019, North Carolina leaders outlined an educational and economic vision for the future by announcing the state’s first attainment goal. The goal is to produce enough qualified North Carolinians to meet the needs of the state’s economy, which is projected to be 2 million adults ages 25-44 with a postsecondary credential or degree by 2030. To get there, the state needs to expand access to higher education and improve attainment for a wider range of North Carolinians.

One major step? Streamlining the movement of students like Wright from community colleges to four-year colleges.

Origins of the transfer system

“We must give our children the quality of education which they need to keep up in this rapidly advancing, scientific, complex world. They must be prepared to compete with the best in the nation, and I dedicate my public life to the proposition that education must be of a quality that is second to none. A second-rate education can only mean a second-rate future for North Carolina.” — Gov. Terry Sanford in 1961

The North Carolina Community College System we know today was born out of the unification of two separate educational institutions — junior colleges focused on liberal arts education and industrial education centers focused on technical and vocational education. Both were established by the North Carolina General Assembly in 1957, but it wasn’t until 1963 under Gov. Sanford that they were united as the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS).

Community colleges continue to serve the dual role of preparing students academically and technically, represented by curriculum courses and continuing education courses.

In 1995, the General Assembly strengthened the role of community colleges in preparing students to transfer to universities. In addition to establishing common course numbering among the community colleges, legislation required the UNC Board of Governors and State Board of Community College to “develop a plan for the transfer of credits” between the two systems.

This led to the first Comprehensive Articulation Agreement (CAA), an agreement signed in 1997 that set the rules for transferring credit between the 58 community colleges, 16 UNC System schools, and signatory independent colleges and universities. The first Independent Comprehensive Articulation Agreement (ICAA) was signed in 2007 between the state’s independent colleges and universities and the community college system.

In 2013, the General Assembly passed a law requiring biannual reviews of the CAA leading to a substantial revision in 2014. Since then, both the CAA and the ICAA have been updated and the number of students transferring from community colleges to four-year schools continues to grow.

“When individuals can see that they can get the first two years of education without building up massive debt and then go to a university after that,” said Dennis King, former president of Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, “that’s going to become very appealing to people.”

For many of these transfer students, starting their higher education at a community college and transferring is the only way they can afford to get a bachelor’s degree. Others had never considered getting a four-year degree, but their time at community college changed their perceptions of their future and transferring allowed them to pursue their dreams.

Improving pathways from community colleges to four-year universities is vital for our students, our state, and our future. Getting a good job today requires more than a high school diploma, yet just shy of half of North Carolinians ages 25 to 44 have some form of postsecondary education currently. If these trends continue, North Carolina is projected to have 400,000 fewer workers in 2030 with the education needed than what the workforce will demand.

Community colleges also enroll a higher share of low-income students and students of color, both of which are underrepresented in higher education. Improving the transfer process will allow more of these students to access the benefits of a four-year degree.

A critical part of the transfer process: articulation agreements

Our state is so rich, so complex, so diverse, and so different in terms of our 58 community colleges, our UNC institution institutions, our private partners, etc. To develop structures and strategies that accommodate that diversity — it’s really difficult.” — Audrey Jaeger, executive director at The Belk Center for Community College Leadership and Research

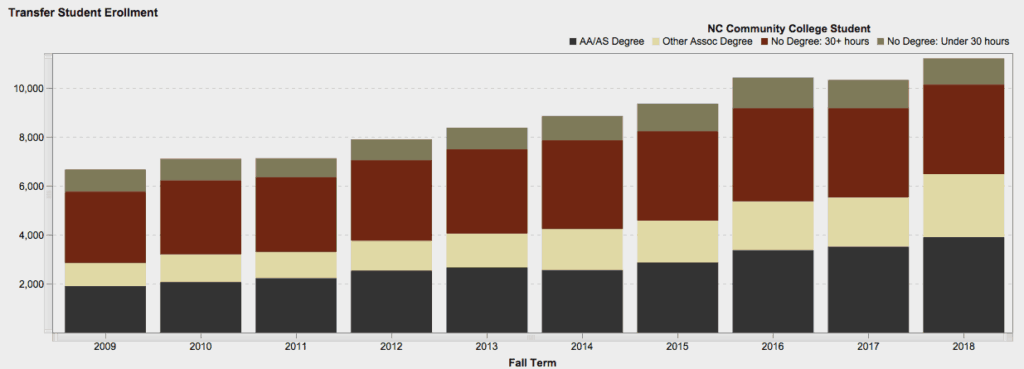

In the fall of 2018, more than 11,000 students transferred from one of North Carolina’s community colleges to a UNC System university, the highest number of transfers ever. These students are transferring under the revised rules set in place by the 2014 Comprehensive Articulation Agreement (CAA).

Perhaps the most important provision of the CAA is the guaranteed admission to one of the 16 UNC System schools for anyone who completes an associate degree in arts or in science at a North Carolina community college. To be clear, it only guarantees admission to one school, which may not be the student’s school of choice.

Guaranteed general education transfer credits, known as the UGETC courses, are another key feature of the CAA, and one that especially helps students who transfer before they earn a degree. If a student earns an associate degree, they are guaranteed to have their lower-division general education requirements fulfilled. But for students who transfer early, the loss or inapplicability of credits has been a problem. Under the CAA, there are clearly defined classes that are guaranteed to transfer for general education credits.

After the CAA, there is more clarity for transfer pathways, too. Each major at each university has its own requirements. The CAA required every college in the UNC system to publish “baccalaureate degree plans” that clearly outline which credits can be transferred and count toward each major. As long as students know which major they will choose and which school they will attend, they can plan which classes to take.

Those plans are not very useful if they are not current, however. That is why the Transfer Advisory Committee is a key, though often overlooked and underfunded, part of the CAA. The committee is comprised of administrators from the community college and UNC systems and is responsible for monitoring schools to make sure they are in compliance with the CAA. The committee is also required to report on the CAA to the state legislature every year.

The oversight and enforcement of the advisory committee is a big part of why the current CAA is successful, said Wesley Beddard, system vice president at the North Carolina Community College System. The first iteration of the CAA was passed in 1997, but it fell apart pretty quickly because there was no way to keep it current, Beddard told EdNC.

“This process is designed to continuously improve,” Beddard said. “The primary problem with the … 1997 agreement was that we did it and we didn’t tend it. Right, the garden got a lot of weeds over time, and we didn’t keep it current. That can’t happen with the current agreement because it’s evolving.”

The CAA also serves as a foundation upon which other agreements are built, often between one community college and one four-year college. These “bi-lateral” articulation agreements serve the specific needs of a community college’s population. For example, if a college sees that a lot of its students are interested in agriculture, it may reach out to North Carolina A&T or North Carolina State and try to set up transfer rules that help their students get degrees in Agricultural Education or Agribusiness Technology.

When there are common areas of focus across the state and not just at particular colleges, a Uniform Articulation Agreement might be in order. These are transfer agreements focusing on specific degrees that are in high demand across the entire state. These currently cover associate degrees in early childhood education, engineering, fine arts, and nursing. Again, having the CAA as a foundation helps make these additional agreements possible.

“We’d probably still be working on that if it weren’t for the CAA,” Beddard said of the engineering associate uniform articulation agreement.

Administrators in the community college and UNC system offices credit the CAA for increasing the number of students completing associate degrees and transferring. But Audrey Jaeger, executive director at the Belk Center, is cautious about making those kinds of causal claims. Without more research, there are just too many factors at play to know exactly why more students are transferring, why more are earning their degrees before transferring, or which parts of the CAA are actively improving the systems and which could use more work.

Why transfer is so complex

Higher education in North Carolina is what academics call “institution-driven.” That means even though there is a statewide agreement, the bulk of how transfer actually works comes down to the policies and agreements between colleges. And between the state’s 58 community colleges, 16 public universities, and 36 private universities, there are hundreds of transfer agreements.

The CAA ensures that the credits from the first year at a community college will transfer toward general education credits. For second-year, or “pre-major” courses, students need to be careful to take classes that will count toward their major. The trick is, though, that a class might count at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, but not at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Decreasing confusion and increasing the number of credits that both transfer and apply to a major are important steps for improving community college transfer because when students take a lot of extra classes, they are less likely to graduate on time, or at all. The less efficient the pursuit of a degree, the less likely a student is to graduate, national research shows.

Matt Wright’s story is an example of the challenges transfer students face. Even though Wright is expecting to graduate from NC State relatively quickly – after two-and-a-half years with a business major and two minors – his path hasn’t been very efficient. Of the over 60 hours he transferred to NCSU, about half went toward elective credits rather than his major, he said.

Despite the hurdles, Wright thinks community college is a good option, especially if the student earns an associate degree.

“If nothing else you can have that associate to fall back on, which is so much better than going to a four year for a year and a half and having nothing,” Wright said. “So I would just say go get the associate and then you can transfer and it’s a lot easier to transfer to a university that you want to go to than it is to go straight out [of high school].”

The next articles in this series will look at the research on transfers and how the community college system plans to further improve the transfer process. Bookmark this article so you can use the glossary below throughout the rest of the series.

Glossary of terms

2+2: The most basic version of community college transfer when a student attends a two-year college, then transfers to a university to complete two more years to earn a bachelor’s degree.

Comprehensive Articulation Agreement (CAA): An agreement signed in 1997 and updated in 2014 that sets the rules for transferring credit between the 58 community colleges and 16 UNC System schools.

Independent Comprehensive Articulation Agreement (ICAA): Similar to the CAA, the ICAA is an agreement signed in 2007 that sets the rules for transferring credits between the 58 community colleges and 30 signatory North Carolina independent colleges and universities.

Bilateral articulation agreement: An agreement setting the rules for transferring credits between two institutions (i.e. one community college and one university).

Uniform articulation agreement: Agreements focusing on specific degrees that are in high demand across the entire state. These currently cover associate degrees in early childhood education, engineering, fine arts, and nursing.

Baccalaureate Degree Plans (BDP): Required by the 2014 CAA, these plans are developed by universities and outline pathways leading to associate degree completion, admission into a major, and baccalaureate completion at the university.

Associate of Applied Science (AAS) degree: AAS degree programs are designed to give students training in technical areas to prepare them to enter the workforce. They are not protected under the CAA.

Universal General Education Transfer Component (UGETC): Set of community college courses that are guaranteed to meet general education requirements at all UNC institutions.

Transfer-out rate: The percentage of community college students who transfer to a four-year institution within a six-year period.

Transfer-out completion rate: The percentage of students who started at community college and earned a bachelor’s degree from any four-year institution within six years of community college entry.

Lateral transfer: Transferring from one two-year institution to another or from one four-year institution to another.

Vertical transfer: Transferring from a two-year institution to a four-year institution.

Reverse transfer: A process to combine credits earned at the university with credit already earned at the community college to award associate degrees to students who transfer before receiving one.

Behind the Story

EdNC’s Taylor Shain produced the video in this article.

Artwork for this article is by Carol Bono.

Additional reporting for this article was conducted by Jordan Wilkie.

This article was edited by Eric Frederick and Mebane Rash.

Recommended reading