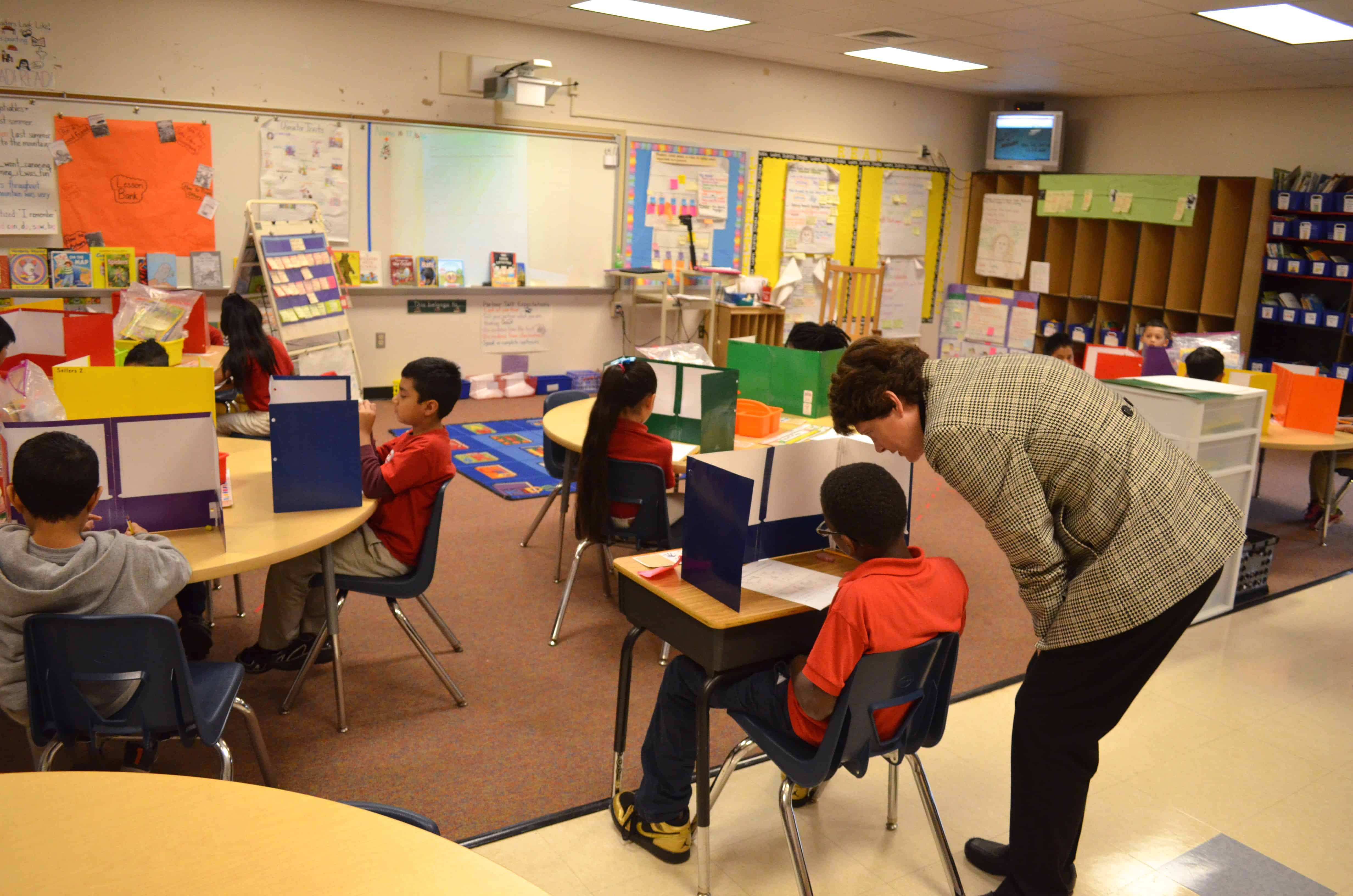

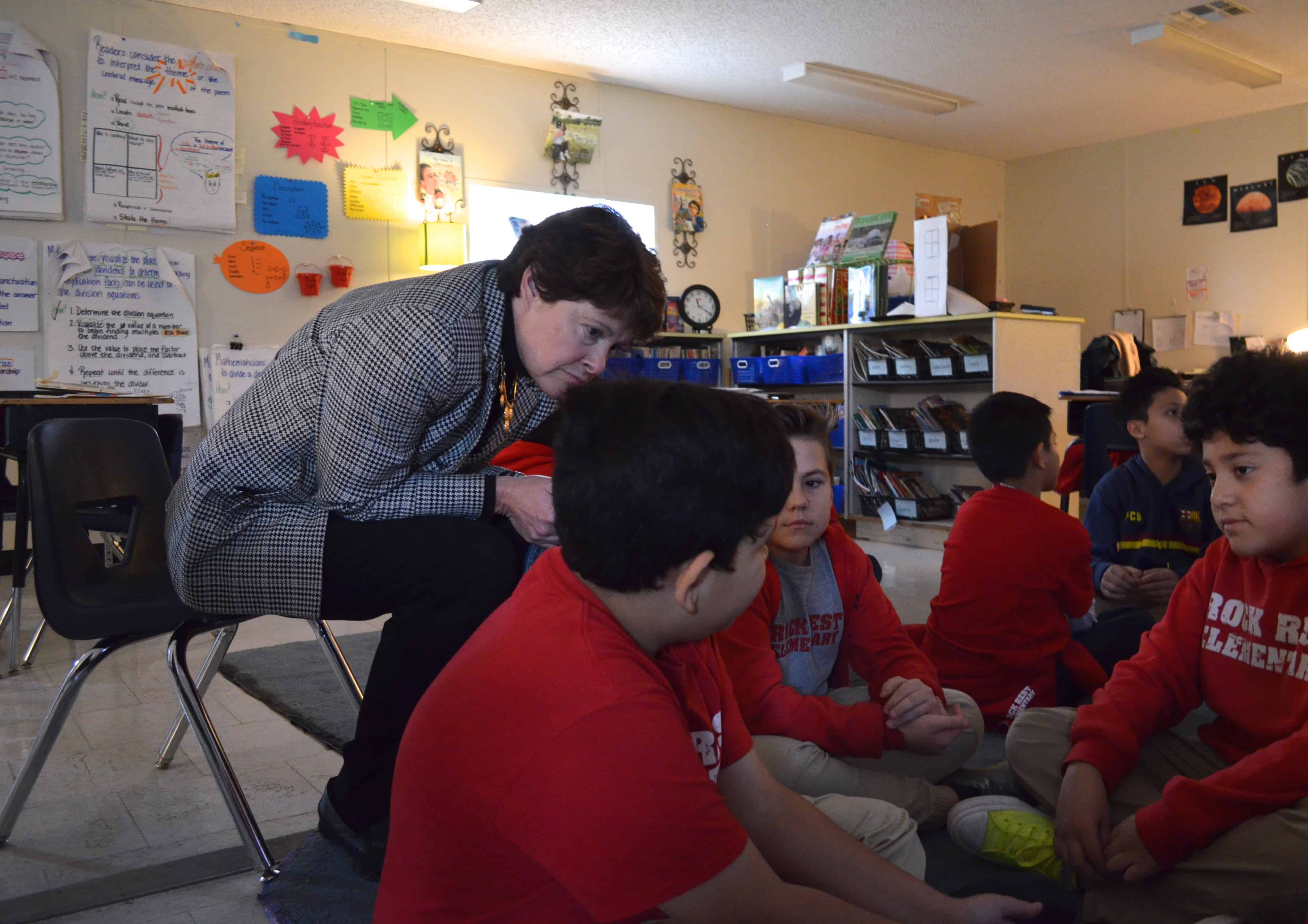

Just before the Christmas holiday, Kristy Thomas roamed various classrooms at Rock Rest Elementary School in Union County to inspect the work of her students and her teachers.

She walked into a second grade classroom where the teacher was combining the importance of literacy with history by having the children learn and discuss historical fiction associated with World War II.

In between classes, Thomas talked about the challenge of teaching children who sometimes don’t have cultural exposure to things many families take for granted. For instance, how do you get a child to understand the concept of boiling point if he or she has never seen a boiling pot of water?

Academic concepts can’t be just words if educators expect students to understand. They have to be illustrative of real-world experiences. That’s how learning sticks.

Thomas has her work cut out for her. Her school is about 632 students strong and the majority of its population speak English as a second language, she said. At the same time, the amount of students who qualify for free-and-reduced price lunch is high. For the 2014-15 school year, the school had about 660 students. Of that, 584 qualified for free lunch and 30 qualified for reduced-price lunch. If you’re counting, that’s well over 90 percent of the school.

And these challenges took their toll on the school historically.

When Kristy was brought into Rock Rest about six years ago, the school was in the bottom five percent of the state for performance.

The state Department of Public Instruction decided to intervene in the school through the TALAS program under the federal Race to the Top program. TALAS stands for Turning Around North Carolina’s Lowest Achieving Schools.

Thomas was brought in specifically to help improve the school. The state allowed her to bring in her own team, and half of the teachers were let go, with Thomas having a summer to bring in new staff.

Six years later, the results are impressive. In the most recent round of school performance grades, Rock Rest was a B.

From the beginning, Thomas says Rock Rest has been a work in progress. The goal is incremental improvement, not transformation overnight.

“When you’re at a school that’s transforming, you don’t bite the elephant off and say we’re going to be an A, That’s a joke,” she said. She added later: “We just bit off little pieces at a time.”

Read some of our previous research on the transformation at Rock Rest here.

The Role of the Principal

Nancy Barbour is the director of District and School Transformation at DPI. It was this department that oversaw the transformation of Rock Rest all those years ago, though the department had different leadership at the time.

Barbour says that high-achieving principals are vital to turning around any low achieving school. And she’s not alone in her assessment.

A 2011 Wallace Foundation report laid out the importance of school leadership in turning around low-performing schools. The report stated this unequivocal remark:

“…there are virtually no documented instances of troubled schools being turned around without intervention by a powerful leader,” it stated.

It goes on to say:

“Investing in good leadership is also a particularly cost-effective improvement strategy: who better than a highly-skilled, well-prepared principal to influence the teaching that goes on throughout an entire school?”

Barbour says there are two roles that transformational principals play which schools can’t turnaround without.

First off, she says principals are responsible for setting “the tone for improvement and expectations in the building.”

Second, she says they have to be the instructional leaders.

“The principal has to determine if what’s being taught is also what they’re expecting for children to learn,” she said.

Thomas would agree with those assessments, though she uses different words to say them.

“The principal has to have the vision,” she said. “They have to envision what they see their school being in small increments.”

Furthermore, she says in a low-performing school, the principal must be a cheerleader.

“You have to have the ability to promote the positive, because it’s not easy in education today to promote the positive,” she said.

Both Barbour and Thomas agree that the role of the principal has changed over time. Barbour describes the traditional role of the principal as being more of a manager. Thomas likens the old role to being more akin to a leader in the Armed Forces.

“It used to be the principal was in charge, and sort of that military leadership,” she said. “It was top down.”

But that style has gone by the wayside, at least when it comes to low-performing schools.

A Hands-On Approach

When I visited Rock Rest before the Christmas holiday, the visit started with Thomas meeting with her group of fifth grade teachers. They went over tests recently taken by various students and discussed ways to improve the children’s performance.

Thomas could name individual children, and it was clear that none of the teachers had a student Thomas didn’t know personally. She talked strategies that might improve how the students learned. She discussed the possibility that teachers might need to reword questions, because maybe they were confusing to students.

Thomas even suggested that perhaps, in review, the students should come up with their own questions. That way teachers could see how they thought about the problems they were trying to tackle.

Her approach was decidedly hands on. And these meetings aren’t infrequent, but rather a regular occurrence.

“Everybody has to have a hand in the vision. Everybody has to have a hand in the work. Everybody has to have a hand in the creation of ideas,” Thomas said.

Edgecombe County’s Approach

Rural Edgecombe County has 56,552 residents living a little more than an hour from North Carolina’s capital city. But instead of the affluence found in Raleigh, Edgecombe has a median income of $31,615 with 38.1 percent of its children below the poverty line.

In 2012, Edgecombe County Public Schools brought in a new superintendent: John Farrelly. The school system faced many problems, including the number of students choosing to attend the North East Carolina Preparatory School, a charter school, rising from 397 students in 2013 to 902 in 2014 to 1,222 in 2015, according to the Statistical Profile published by the N.C. Department of Public Instruction.

Farrelly thought innovation was the key to success in the district, and he tackled troubled Martin Millennium Middle School as his test case. He previously had called it a “school on fire” with “horrific” rates of student achievement.

He brought in Erin Swanson to become the principal, and between the two of them and the team on the ground, they transformed Martin Millennium into an academy that embraced the global schools model.

Now, Martin Millennium is a beacon of hope in Edgecombe.

With Swanson taking the helm of Martin Millennium, Farrelly was putting into place not just a person but a philosophy for change: get the right leaders and we will see transformation.

“I would say that my number one priority for several years is getting the right leaders in place around the district, particularly for low performing schools,” he said.

Many of those leaders came out of the Northeast Leadership Academy, a principal prep program operated out of North Carolina State University. In a different article, we will talk more about principal preparation and its role in creating great principals.

But what makes the leaders Farrelly chooses — like Swanson — the right ones for the job? He has a few ideas.

”It’s a process where you have to come in, observe, ask a lot of questions,” he said.

The first step is getting a sense for the culture and what’s happening on the ground. Change can’t happen until a leader knows what a school is like.

And then the leaders he brings in have to be able to assess a school’s strengths and weaknesses and come up with a blueprint for improvement.

Farrelly is unusual in that he doesn’t always choose someone with the most experience or a big track record to helm his schools. Many of his decisions are made by gut.

“I try to hire people who I’d want to get behind,” he said, adding later: “It’s hard work, and when you’re dealing with schools where many of the kids are significantly below grade level, it’s not for everyone.”

It’s talent he is looking for above anything else. Talent for change. Passion for children. Dedication to the work. All of those things count more than anything that can be read on a resume.

When Swanson came in to Martin Millennium, she did exactly what Farrelly was looking for: she got a sense of the culture of the school, met with various community stakeholders to understand what they wanted from their school, and examined evidence-based research to see what strategies might work in her school.

It was that research piece that helped her determine that Martin Millennium should have a Spanish-language immersion program.

“We knew there was great value in having our students immersed in the language and culture, and knowing people are different from them but that there are similarities,” she said.

But much like Thomas at Rock Rest, Swanson said it is important for principals to understand that turning around a school is a process. It doesn’t happen overnight.

“A truly excellent principal is able to understand the capacity of the staff. Understand where the staff mindset is at the time, and be able to scaffold the work, so that it is ambitious but so that it’s still viable,” she said.

The Low-Performing School Problem

North Carolina has a problem with low-performing schools. The problem is that there are so many of them, and the state has appropriated the dollars to tackle only a fraction of them.

The most recent release of the school performance grades ended with 489 low-performing schools and 10 low-performing districts.

For a district to be labeled low performing, more than half of the schools must be low performing. For a school to be labeled low performing, it must receive a D or F and not exceed academic growth.

The year before the state identified 581 schools as low performing, with 15 districts designated as low performing.

The boom in low-performing schools dates to a change in definition put forth by the General Assembly before the release of the 2014-15 grades.

Prior to the General Assembly’s new definition, low-performing schools were those that did not meet growth and had less than 50 percent of students scoring at or above Achievement Level III (there are five achievement levels total) on End-of-Grade and End-of-Course tests. In 2013-14, when the prior definition applied, only 367 schools were low performing. That means the number increased from 2013-14 to 2014-15 by 214 schools for a 58.3 percent increase. As mentioned, it dropped some in the most recent release.

Still, even with some slight progress, the fact remains that the number of low-performing schools is too many for the states District and School Transformation team to tackle. They can only handle a small subset of those schools — the worst.

That leaves districts and principals to turn around the rest, which means a piecemeal approach to improving academic achievement.

Another problem with the definitions of low performing put forth by the legislature is that it penalizes principals of low performing-schools. District superintendents have to take some sort of action against a principal if he or she had been at the school more than two years — the possible options include remediation or dismissal.

The problem is that it often takes more than two years for a school to turnaround. Barbour says that looking at the progress over 3 to 5 years makes more sense.

“Low performing is so complex that a letter grade and a growth status don’t tell you everything about a school,” she said.

Having said that, she says it’s possible for a new principal to see some progress in the first year, though that won’t necessarily translate to a school inching out of its low-performing school status.

She also said that remediation plans can sometimes be a good thing. Regardless, a full discussion of the intricate needs and nuances of a school should be discussed before a district decides to dismiss a principal of a low performing school, she said. Transformation is going to take time.

“If you get a transformational leader in a school, then you’re going to see transformation,” she said. “It’s going to take time. But you’re going to see it.”

Recommended reading