In 2013, North Carolina became the first state in the country to remove salary increases for educators with advanced degrees, citing evidence that master’s degrees do not raise student test scores (Section 8.22 of S.L. 2013-360). Since then, legislators have introduced multiple bills to restore advanced degree pay for educators, and the debate around whether or not to restore the pay increases has raged on.

Critics of advanced degree pay cite numerous studies that indicate teachers with master’s degrees are no more effective at raising student test scores than teachers with bachelor’s degrees. Proponents of the pay increases view advanced degree pay increases as a tool to keep experienced teachers in the classroom and as a signaling device that rewards a teacher’s choice to further their education, among other things.

In this piece, we’ll consider the way North Carolina’s salary schedule functions, the data around master’s degree pay increases both nationally and in North Carolina, and some of the major findings from recent research on this issue. Finally, we’ll see what over 600 North Carolinians had to say about this issue.

A look back

Prior to the 2014-15 school year, teachers and instructional support personnel in North Carolina with advanced degrees, such as a master’s or doctoral degree, received a 10 percent salary increase paid for by the state. After these salary increases were removed in 2013, teachers and instructional support personnel who were already receiving the extra pay were grandfathered in to that pay schedule, as were teachers and instructional personnel who completed at least one graduate course prior to August 1, 2013 (Section 8.3 of S.L. 2014-100).

Since then, multiple bills have been filed to restore master’s pay without success. In 2015, Senate Bill 107 proposed restoring master’s degree pay for all teachers and instructional support staff based on the policy that was in effect before 2013, but the bill died in committee. In 2017, Senate Bill 664 proposed restoring master’s pay salary supplements for both teachers and instructional support staff, but the bill also died in committee.

In early February, a bipartisan group of state Senators introduced Senate Bill 28, titled “Restore Master’s Pay for Certain Teachers.” That “certain” phrasing in the title refers to the fact that the bill would restore master’s pay only for teachers who get their graduate degree in the subject that they’re teaching, a deviation from the previous policy in place before it was repealed in 2013. For example, a teacher holding a master’s degree in school administration would not qualify for the salary increase and neither would instructional support staff in the school with advanced degrees.

A brief primer on North Carolina’s salary schedule

In North Carolina, salaries are administered in a traditional step-and-lane schedule. The “step” refers to how many years of experience a teacher has. For each year of experience, a teacher moves one “step” further, often receiving a salary increase at each step along the way. However, not every step comes with a salary increase — for example, a teacher with a bachelor’s degree has the same annual salary from 15 years of experience through 24 years of experience. The final “step” is reached when teachers hold 25 years or more of teaching experience.

The “lane” refers to what salary schedule the teacher takes steps within. For example, North Carolina offers different “lanes” for teachers who hold a bachelor’s degree, teachers who hold a bachelor’s degree with National Board certification, teachers who hold a master’s degree, and so on. Each of the salary lanes — beyond the bachelor’s degree lane — have steps that are supplemented based on the credential a teacher holds. For example, in the 2018-19 salary schedule, teachers with four years of experience who hold a bachelor’s degree have an annual salary of $39,000. Teachers with four years of experience who hold a bachelor’s degree and National Board certification have an annual salary of $43,680, and teachers with four years of experience who hold a master’s degree and National Board certification have an annual salary of $47,580.

Beyond the step-and-lane schedule, local districts can provide salary supplements to their teachers. In Wake County, the average teacher salary supplement for the 2017-18 school year was $8,649, but in some rural counties — including Bertie, Clay, Graham, and Swain — no salary supplements are offered. The state also provides performance bonuses for teachers in certain grades and subjects based on their EVAAS growth scores. And, in the 2017-18 school year, six districts in the state (Chapel Hill-Carrboro, Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Edgecombe, Pitt, Vance, and Washington) began piloting advanced teaching role programs where teachers are paid using alternative models, such as offering bonuses for teachers who take on leadership positions or produce good student test scores.

A look at the numbers

Nationally, earning an advanced degree is a common factor in how school districts increase teacher pay. Of the over 145 school districts included in the National Council on Teacher Quality Teacher Contract Database, 88 percent offer additional pay to teachers who hold master’s degrees. There are just 14 districts in the database that do not offer additional pay for master’s degrees — and that’s where you’ll find the four North Carolina districts included in the sample: Wake County, Winston-Salem/Forsyth, Cumberland County, and Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

As of the 2015-16 school year, 57 percent of public school teachers in the U.S. held an advanced degree (master’s degree, educational specialist degree, doctoral degree) according to the National Center for Education Statistics. That is a 10 percentage point increase from the 1999-2000 school year when just 47 percent of public school teachers held an advanced degree. The share of secondary school teachers with advanced degrees (59 percent) is slightly higher than the share of elementary school teachers with advanced degrees (55 percent). The share of teachers with an advanced degree is lower in North Carolina — as of the 2011-12 school year, 41.6 percent of public school teachers in the state held an advanced degree.

A 2015 study by Helen Ladd and Lucy Sorensen found that 42 percent of middle and high school teachers in North Carolina held a master’s degree in the 2012-13 school year. A quarter of those master’s degrees were earned before the teacher started teaching, with the others earned at some point during the teacher’s career. The most common time for a teacher to earn a master’s degree was four to six years into her career.

Ladd and Sorensen also consider what type of master’s degrees these teachers hold and find that degrees in school administration are some of the most common degrees at the post-entry level. The study goes on to state: “While such degrees may be socially valuable, it is hard to make the case that they are likely to make a teacher more effective in raising student test scores.”

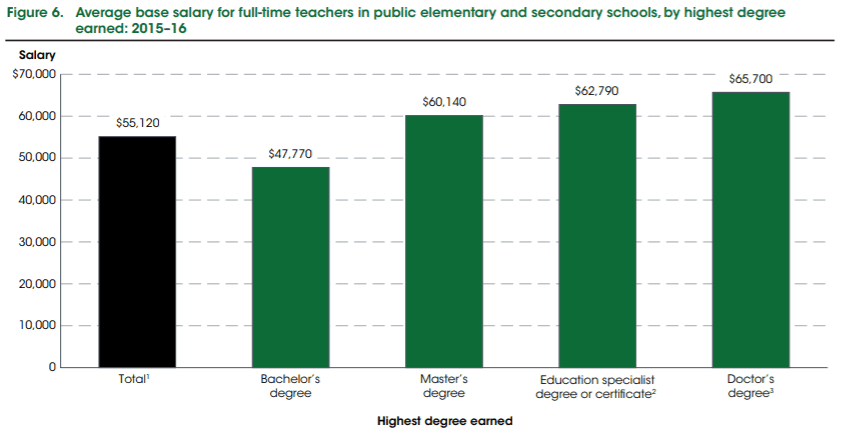

In the 2015-16 school year, the national average salary for teachers in public elementary and secondary schools with a master’s degree ($60,140) was roughly 20 percent higher than the salary for teachers with a bachelor’s degree ($47,770). Among the 100 largest districts in the country and the largest districts in each state (121 districts), the National Council of Teacher Quality finds that the average salary for first-year teachers with a master’s degree ($47,385) is roughly six percent higher than the average salary for first-year teachers with a bachelor’s degree ($44,625).

The salary supplement for teachers in North Carolina with a master’s degree (those grandfathered in to the former policy) is 10 percent — but what does that really mean? Based on data from the national Schools and Staffing Survey of 2003-2004, the average salary bump in North Carolina for a teacher with a master’s degree over one with a bachelor’s degree was $4,417. Just 1.09 percent of North Carolina’s total education expenditure was spent on master’s degree salary supplements, which equates to $97 per student. For comparison, the same data finds that master’s degree pay salary supplements accounted for 2.48 percent of South Carolina’s education spending and 1.63 percent of Tennessee’s education spending, for a cost of $222 and $139 per pupil, respectively.

What does the research say?

There are a variety of different policy questions concerning the topic of advanced degree pay. There’s the question of recruitment: Could salary increases for advanced degrees attract more people to the teaching profession in the first place, or attract them to teach in North Carolina from other states, many of which offer advanced degree salary supplements? Then, there’s the question of retention: Can salary increases for advanced degrees serve as incentives for teachers to remain in the profession?

However, much of the debate around restoring master’s pay is focused on the question of effectiveness — whether or not there is a link between having a master’s degree and improving student test scores — and that’s what this section will focus on.

Much of the available research suggests that advanced degrees do not lead to improved teaching. This 2014 literature review summarizes the findings of 53 studies, based on rigorous selection criteria, to determine to what extent teacher characteristics can explain teacher effects on student test scores:

“The main findings of the literature on the effects of having an advanced degree are that students from teachers with a master degree do not perform better or worse than students from teachers with only a bachelor degree. This conclusion is rather persuasive, since a wide range of both older and more recent studies among different grade levels and different subjects do not find students from teachers with an advanced degree to perform significantly better or worse than students from teachers which only obtained a bachelor degree.”

Two studies in the literature review found that holding subject-specific master’s degrees in science and math were associated with higher student math scores, but the design of those studies does not allow for causal inference.

A 2011 study by Matthew Chingos and Paul Peterson uses estimations from value-added models to measure teacher effectiveness in reading and math for fourth- through eighth-grade students in Florida over eight years. The study found that “neither holding a college major in education nor acquiring a master’s degree is correlated with elementary and middle school teaching effectiveness, regardless of the university at which the degree was earned.” The study did find that teachers generally do become more effective after a few years of teaching experience.

The 2015 study by Helen Ladd and Lucy Sorensen uses longitudinal administrative data on teachers and students at the middle and high school level in North Carolina from 2006 to 2013. Despite specific attention to selection bias — as some teachers are more likely to decide to obtain a master’s degree than others — the study confirmed previous findings that teachers with master’s degrees are no more effective than those without one. The study does find one consistently positive effect of attaining a master’s degree — lower student absentee rates in middle school — and says that “further research could determine whether these benefits extend to other student behavioral dimensions.”

Another 2015 study, this one by Moiz Bhai and Irina Horoi, also uses teacher and student data from North Carolina — but this time, the study uses sets of twins to estimate how teacher characteristics, such as experience and advanced degrees, affect achievement in math and reading. The use of twin siblings in this study controls for external factors that may impact student achievement, such as a divorce in the family, gang activity in the neighborhood, or having a new principal at a school. The study finds that years of experience and National Board certification have “positive and significant effects” on student achievement in reading and math but finds inconclusive effects for advanced degrees.

In a 2018 study that also uses North Carolina data, Kevin Bastian looks at teacher value-added and evaluation rating data to estimate the effects of graduate degrees inside and outside the teachers’ area of instruction. Bastian finds in several comparisons that in-area graduate degrees (such as a master’s in math held by a math teacher) benefit teacher effectiveness, as measured by value-added, and predict higher evaluation ratings than those for teachers with undergraduate degrees only. However, out-of-area graduate degrees (such as those in school administration or counseling) had negative or insignificant impacts on teacher effectiveness.

All of the above analyses include a focus on student test scores and find that teachers with master’s degrees are not, on average, more effective than those without master’s degrees in raising those test scores. Therefore, if the primary goal is to raise student test scores, salary increases for teacher’s with master’s degrees cannot be justified.

However, holding a master’s degree may have an impact on other student behavioral factors, as the Ladd and Sorensen study touches on in its finding that teachers with master’s degrees have lower rates of student absences in middle school. Ladd and Sorensen also comment on the potential of master’s pay to function as a retention incentive:

” … our descriptive finding that teachers are most likely to earn graduate degrees during their 4th through 6th years of teaching suggests that the current policy may increase teacher retention during this critical time within their career. The timely salary raise and human capital investment could impel teachers to remain in the profession and continue their on-the-job learning. This retention is especially important given that, as has been shown elsewhere, teacher productivity rises through at least 12 years of experience, and teacher exit early in the career has become more common.”

Nancy from Caldwell County offered the following thoughts in response to this research:

“What’s missing from the original study is a discussion of limitations. How much effect on test scores can an advanced-degree teacher have in one year? Apparently, students are more likely to attend their classes — that’s a start. To determine whether teachers who advance their education are better educators, it seems that a better study design would be to follow students who are ONLY taught by teachers with advanced degrees. In the meantime, I think that teachers who obtain an advanced degree should receive additional compensation.”

North Carolinians weigh in

In a recent Reach NC Voices survey, 82 percent of respondents said they are in favor of restoring master’s pay for educators with advanced degrees — but there’s disagreement over the nuances of the policy. The survey ran from Feb. 18 to Feb. 22 and included 601 respondents.

Of the participants who said that advanced degree pay increases should be restored, 60 percent said they should be restored regardless of the type of advanced degree the teacher holds and 33 percent said it should be given only if the advanced degree is in the teacher’s area of instruction.

Here’s a representative sample of what respondents had to say:

“Obtaining a Master’s Degree is just as challenging as obtaining National Board Certification. If NBCT’s deserve higher pay for earning that credential then teachers who obtain a Master’s degree also deserve that pay.” — Amy in Onslow County

“It’s hard to encourage students to pursue further education if their own teachers aren’t being recognized for pursuing further education.” — Anonymous in Pitt County

“I believe if you are putting forth money and time to attain a degree you should be compensated. However, if the state is paying for this bonus it should benefit the students that you are working with.” — Tracy in Jones County

“We do not pay dentists or doctors based on the amount of cavities that their patients do or do not have or how well their patients are. You pay doctors and dentists because they went to school and earned the degree. Why should teachers be treated any differently? If teachers have gone to school and earned a degree, they should also be compensated accordingly.” — Beth in Burke County

“The rigor [of] the program should matter. An online degree in education is not the same as a graduate degree with original research and thesis defense.” — Chris in Cherokee County

“Masters and doctorate degrees in specific areas of teaching are quite valuable. I spent 4 years earning a doctorate, wrote a dissertation on a subject that directly affects my students, and have presented my research locally, regionally, and nationally, yet I receive no stipend. My education has greatly improved the value of instruction my students receive.” — Davie in Wake County

“There should be metrics around the incentive. Being that there was research done to prove that the degree does not lead to improve teaching, it should also be used to measure where it is used to improve. In my opinion, this will motivate those that teach to ensure they are improving in order to receive the bonus. In essence a performance review.” — Tashan in Durham County

What are your thoughts on restoring master’s degree pay increases? Weigh in below.

Recommended reading