During first block at Brevard High School, Isaiah Lefler and Graham Green are in front of an Erlenmeyer flask with liquid swirling like a small tornado. They have simulated urine, simulated mars dust, and nitrifying bacteria. Their overall goal is to try and turn urine into fertilizer for plants.

These two students are seniors and have been in the high school’s TIME for Real Science program since freshman year. What is TIME and how is it allowing students to participate in the same competitions as Nobel Laureates?

The history of TIME

TIME stands for Time Inquiry Matter Explore, and it started in 2006 when Mary Arnaudin, a North Carolina Cooperative Extension 4-H agent, and Jennifer Williams, a 20-year science and math teacher at Brevard High School, joined forces. Arnaudin was looking for a teacher to partner with to apply for a Student STEM Enrichment Program grant (SSEP) through the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (BWF).

The curriculum director of the district at the time made the introduction. Together, they wrote the grant, and were awarded the funding for the initial TIME program in 2006.

TIME started with one kick-off week in the summer of 2007, and continued as an after school program throughout the academic year. With five teachers from around the county, they took 20 students and performed what Williams calls a week-long summer field study.

“We tried to immerse our kids into science in our county, because we really, really want them to see that science can be a way to solve problems in your own community.”

Jennifer Williams, Brevard High School

She wanted students to understand how they could be part of the solutions to issues impacting their parents, their neighbors, and themselves. Transylvania County isn’t known for research, like other areas of North Carolina, but it is rich in resources. With over half of the county taken up by protective land, there are specialists and scientists in the area.

“We want them to really see that there’s a reason to do this, and that it can be used to solve problems,” said Williams.

The SSEP grant is set up to fund a summer and afterschool program, but allows for an extension through the year, so TIME leaned more into the extension part to make it work for school. Until 2011, they divided students up into groups during the summer week with one teacher who they would work with before and after school on their projects. The SSEP grant is for three years, but TIME was allowed an extension because Williams and Arnaudin were prudent with funding.

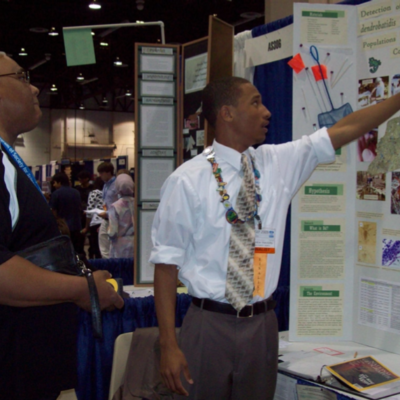

TIME students at Brevard High School. Courtesy of Jennifer Williams

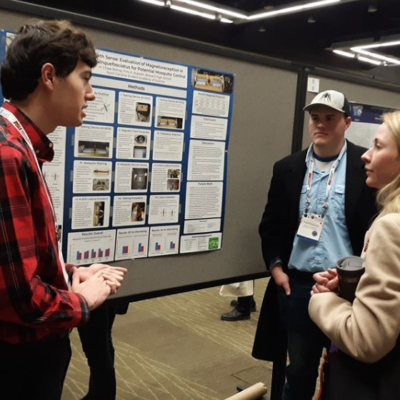

TIME 101 students at Brevard High School. Courtesy of Jennifer Williams

After that grant ran out, Williams was looking for other ways to fund the program while simultaneously thinking, “You know, it’s kind of ironic that we’re waiting until after school to do the real science.” Enter another grant opportunity from BWF, the Career Awards for Science and Mathematics Teachers (CASMT).

Williams applied and was awarded this designation in 2010, which provides $175,000 over five years to the winner and school. They took a year to plan and get the school on board with Williams spearheading a new class. The actual TIME course started in the fall of 2011, and it has taken some shifts in structure throughout its tenure.

Students have to apply to be in the program, and as the years passed, more freshman expressed interest, so they created a TIME 101 class. Here, students work on short, open-ended inquiry labs where they have to design their own questions. Williams explores multiple science areas — physics, chemistry, biology, and more — so the students can feel out what they are most interested in. At the end of TIME 101, students have to come up with a project proposal for the next iteration of TIME, the research class.

Sample TIME projects

- Testing the Efficiency of Local Cyanobacteria and Microalgae in Biophotovoltaic Solar Cells

- Antifungal Activity of Bacteria Isolated from the Endangered Green Salamander

- Evaluation of Magnetoreception in Culex quinquefasciatus for Potential Mosquito Control

- Antimicrobial Activity of Endophytes Isolated from Transylvania County Spray Cliff Plants

- Olfactometer and GC/MS evidence for (E)-2-Hexenal as a semiochemical in the defensive secretions of the kudzu bug, Megacopta cribraria

- Evaluation of Fermented Beverages Produced by Yeast Isolated from Bee Bread

Students choose a partner from class, come up with their project, and then have to present in front of different experts and answer questions. It is now a requirement to take TIME 101 if you want to participate in the TIME research course.

Students who have taken multiple TIME research classes tend to stick with their original partners and topics. With more research, they come up with more questions, and they want to answer them.

“To me, that says a lot,” said Williams. In the end, students become true experts in the field of their choosing.

Experts and competition

Experts are an integral part of the TIME program, and Arnaudin was great at getting kids connected, says Williams. Experts can range from a Pisgah Pest Control employee to a career and technical education (CTE) instructor in the school to a professor from a college out-of-state. Its important to Williams to show students how many resources are in their area.

They invite locals to review the students’ project proposals and their final presentations in TIME 101. The experts judge, ask tough questions, and give them feedback in class (during a usual year).

Competition is a requirement of the TIME research class. This can start with the district science fair, but for many TIME students, it doesn’t stop there. Fifty-four of Brevard High’s students have won trips to national and international science competitions. From California to Texas and Pennsylvania to Washington state, TIME students are well-traveled.

When students travel for competitions, they get to “interact and collaborate with not just judges, but also peers who have been working on projects from around the world,” says Williams. One of her favorite things is to watch her students talk with experts in the field, because they hold their own. She sees their remarkableness come out in those moments.

Duke Energy Foundation and various community businesses, organizations, and even parents of TIME alumni have helped with funding throughout the years. The cost of travel for competitions can add up. Students themselves submitted a grant proposal to the Pisgah Forest Rotary Club last year and received $2,500.

By the end of TIME, 80% of students are thinking more about getting a job in a science-related career, and 70% of TIME graduates declare a major in a science-related topic. In 13 years of TIME, 179 students have taken some version of the class. Kris Petterson, a TIME alumni, explains the value of the programs’ hands-on experience.

“There is such a big difference between learning science from a textbook and learning science in a laboratory setting like research scientists where it is hands on — you are learning in a completely different way.”

TIME alumni Kris Petterson

During her experience in TIME, she was awarded the most Outstanding Project in Microbiology at the American Society for Microbiology at the International Science and Engineering Fair. She is currently at Texas Tech getting her PhD in plant pathology.

What is Williams’ favorite things a student has said to her? That while they were learning science, what they really learned was how to fail. Having an experiment not work isn’t a bad thing, but rather opens up a world of other questions — and that is what science is all about.