Hank Weddington gets a lot of calls from principals in the area surrounding Lenoir-Rhyne University, where he is dean of the college of education. Over the months and years, the calls have started to sound the same. But he never tires of receiving them.

“We need your alumni in our school,” Weddington reports as the driving force behind the calls, a certain pride beaming through with the words. “That always feels good.”

He says the calls, which have come in from almost every principal in the three-county area the Hickory-based institution serves, are the product of several initiatives at the university. But one in particular stands out, and was recognized by a recent national report, and that’s the changes to coursework preparing future educators how to teach reading.

“They have made it very clear that they would like to hire teachers from our institution who are well prepared in teaching reading,” Weddington said.

This week, the National Council on Teacher Quality released its 2020 Teacher Prep Review. In its review of 1,000 elementary education preparatory programs across the country, the Teacher Prep Review lifted up Lenoir-Rhyne as one of just 15 national models.

What is Lenoir-Rhyne doing that’s so special?

A national model for excellence

“I think we do several things very well, but the first thing we do is all of our coursework is really grounded in the science of reading,” said Monica Campbell, who began redesigning the reading coursework five years ago and led its implementation three years ago as coordinator of the elementary education program.

“Everything is based on the scientific research. And the students really grasp the science of reading, which is a tough thing to grasp at their age and without experience.”

Students at Lenoir-Rhyne get this instruction through both systematic coursework over two years, as well as an in-school lab experience where they tutor children at a nearby public school.

The concentrated reading program begins with instruction around emergent literacy, or an explanation of a child’s knowledge of reading and writing skills before they learn how to read or write words. In the first semester of junior year, they also take the Foundations of Reading Primary course which covers phonemic awareness and phonics.

The coursework continues second semester of junior year with Foundations of Reading Intermediate, where they learn word-attach and word-recognition strategies looking at multi-syllabic words and study morphology and how to teach morphology in the schools. The final “big idea” – as Campbell calls it – includes instruction around fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

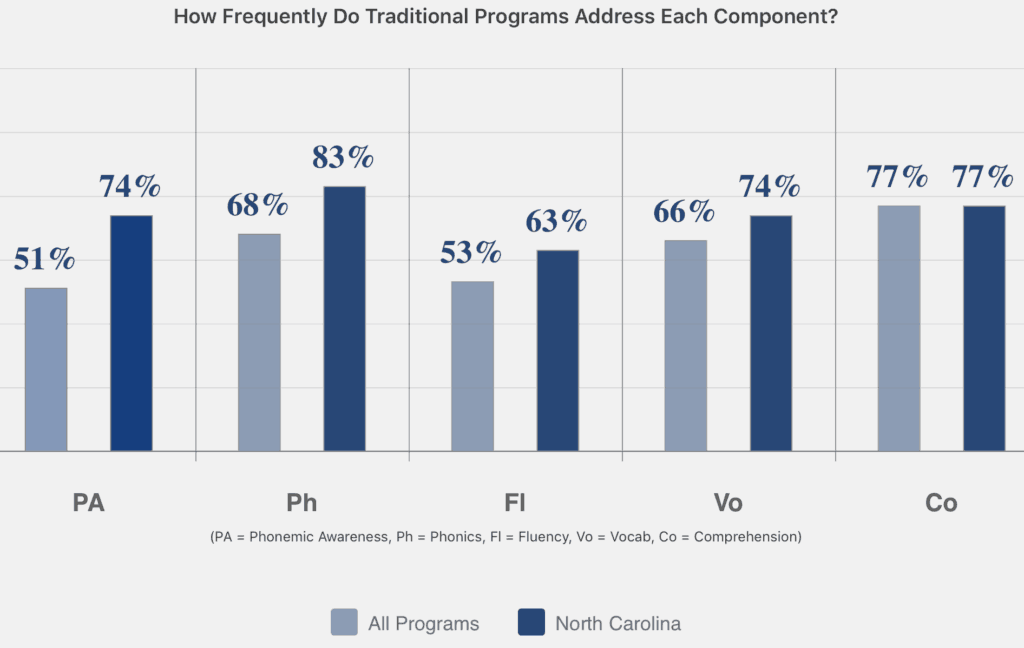

Together, phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension make up the five components cognitive science says builds skilled readers.

Senior year, future teachers take an English Language Arts Method course where they synthesize the information from junior year and add a writing component, guided reading or small group aspects, and progress monitoring.

“One of the things that I found to be most helpful in teaching courses is the required textbook which is the Teaching Reading Sourcebook,” Campbell said. “And it is just phenomenal; it’s very comprehensive. The students are able to read it, and it gives very specific instructions regarding how to assess, what the assessments mean, and then how to teach.”

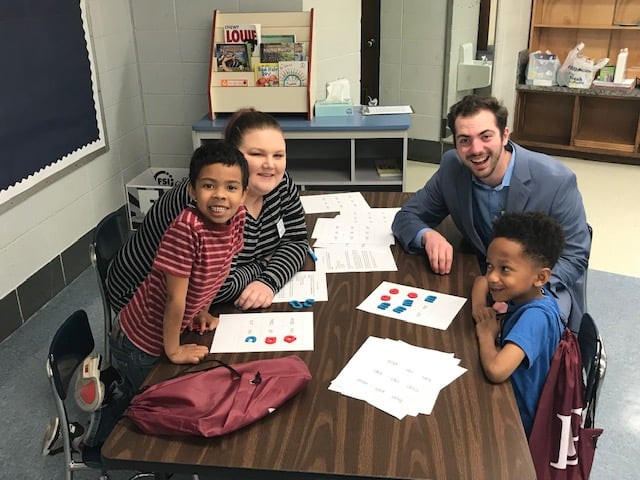

One of the things that stands out about Lenoir-Rhyne is not just that they are teaching the five components of learning to read skillfully, but also how they produce teachers who are skilled in passing these lessons on to young students. That happens through a practical, application-based tutoring approach.

“The thing that’s made the biggest difference is being able to apply it in the classroom as they’re learning it,” Campbell said of her students. “Every day I teach the courses in the school and then the tutors go to our reading lab space. So it’s teaching theory and the research, and then watching the students implement that with their students just minutes after they’ve had the instruction. It’s super powerful to be able to implement it right there in the moment – and to also receive the immediate feedback through the coaching.”

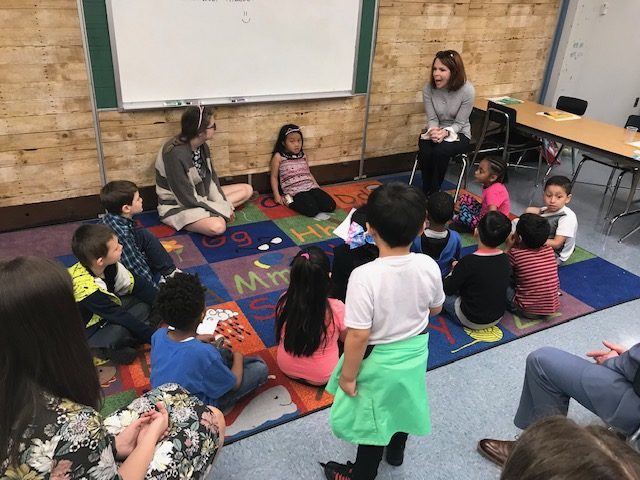

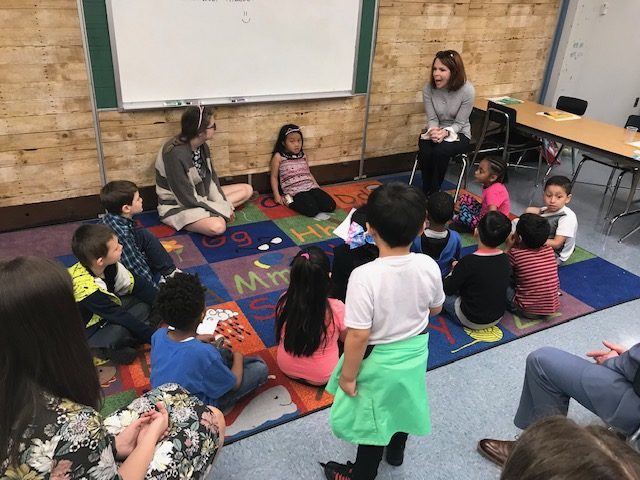

The college of education requires lab work for junior and senior students, where they tutor K-2 students at Southwest Primary, a Title I public school which is among the lowest, socioeconomically, in the Hickory Public Schools system.

A partnership formed through discussions between Weddington and district leaders, Southwest Primary devoted a classroom space for the tutoring. Weddington led efforts to raise $25,000 to outfit the space with furniture, materials, and the latest technology.

“Ultimately, we built a space that’s different than your typical classroom space so that when they come for tutoring it feels like they’ve won the big game as opposed to being sent off somewhere for special help,” Weddington said.

Starting junior year, the Lenoir-Rhyne students visit the lab and are required to assess a striving reader, pinpoint specific areas for intervention, design effective lessons and implement them, and then progress monitor to make sure that the interventions are effective.

“While they’re providing the tutoring, I serve as the coach and will offer real-time feedback throughout the tutoring sessions,” said Campbell, who is trained in Orton-Gillingham and uses a modified Orton-Gillingham lesson plan as she coaches her students throughout the process.

“In the course evaluations, every single year, my students say how much they appreciate the lab opportunities, the tutoring opportunities,” Campbell said. “Having actually taught a student to read is very powerful and motivating. They’re ready to become teachers because they know they can do this thing called teaching reading.”

The five components are pointed to by cognitive scientists as the basis for skilled reading. But it’s not as simple as covering these five components and moving on – the science behind why it works rests on when these components are taught to learning readers, the systematic and explicit approach to instruction, and how they build on each other across early grade levels to produce proficient readers.

For that reason, Lenoir-Rhyne’s students engage in the tutoring over two years – meeting and working with kindergarten students to tutor during junior year and then returning to those same students, now first graders, to continue progress across their senior year.

“What we know about reading instruction is that they really need to leave first grade reading on grade level,” Campbell said. “Our goal is that after receiving the tutoring in kindergarten on some of the foundational skills, then they’ll enter as first graders and have the more small-group remediation so that by the time they leave first grade they are solid – at benchmark or above benchmark – readers.”

In the 2019 spring semester, the college of education provided more than 150 hours of tutoring to 14 striving readers in kindergarten. According to data tracked by the college, 93% of the striving readers were “below benchmark” or “well below benchmark” in phoneme segmentation fluency. As a result of the tutoring, 71% of these students improved their phoneme segmentation fluency scores to “above benchmark” and 15% of the students moved to “at benchmark level” in reading.

Lenoir-Rhyne’s tutoring program seems to be working for the students at Southwest Primary. But it’s also working for the future teachers who are tutoring the kids. Campbell says it’s providing them with the tools they need to go out and get the real work done.

“Teaching reading is rocket science, and I want my students to understand that,” she said. “I want them to understand what the brain is doing when it goes through that process of orthographic mapping. It’s important. And I think when the students do understand the science, they’re more likely to implement programs with fidelity. It’s so important because they’re the ones who are out there who have to make sure they are teaching all students to read.”

Campbell felt called to structure the college’s reading program around the science because she was alarmed at the reading proficiency scores – nationwide, statewide, and also within the county.

“We found a need,” she said. “The literacy rate in Catawba County is disheartening at best. So it was a way to provide that service. I don’t know if anybody else is doing it, but we just know that we must.”

The “must” applies to both the structure of the program and its emphasis on the cognitive science behind reading instruction, she says.

“Without that foundational piece, talking about the science of reading, I really don’t feel anything else matters,” she said. “It’s important for all future teachers to understand that our brains are not wired for the process of reading, so we’re truly changing the shapes of brains, of gray matter, when we’re teaching reading.”

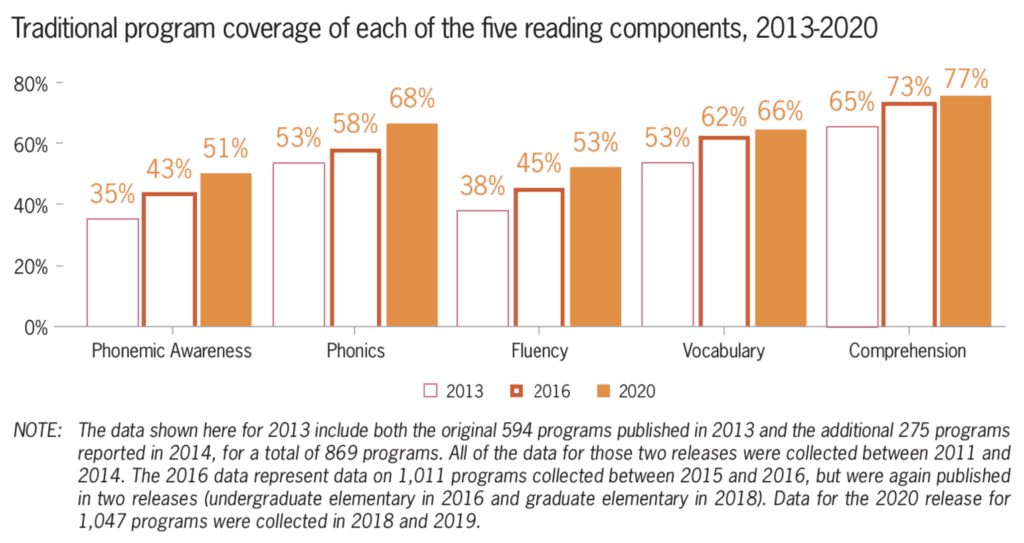

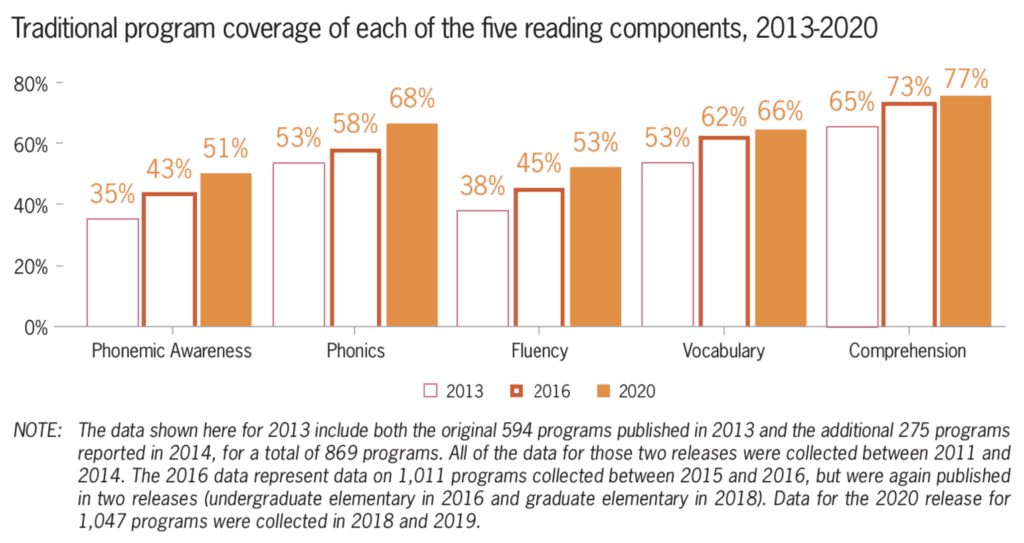

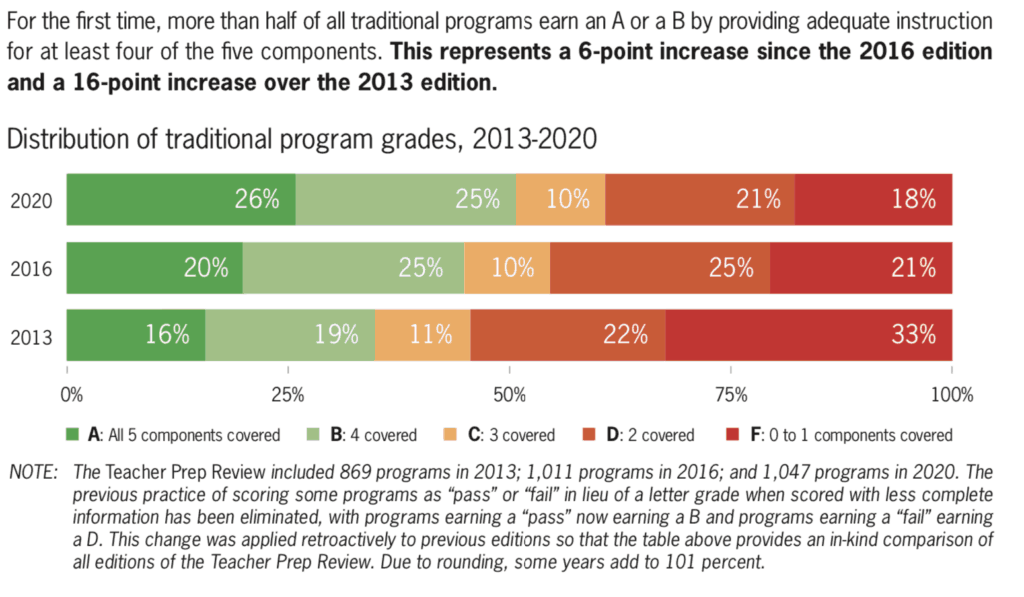

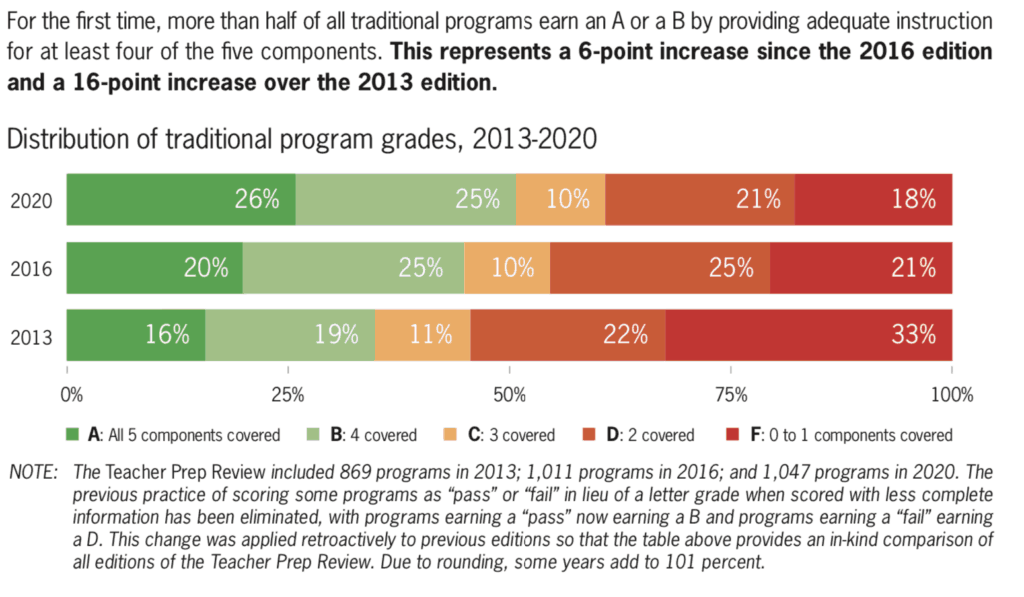

According to the 2020 Teacher Prep Review, more educator prep programs are exposing their future teachers to this science.

NCTQ’s findings on preparing future reading teachers

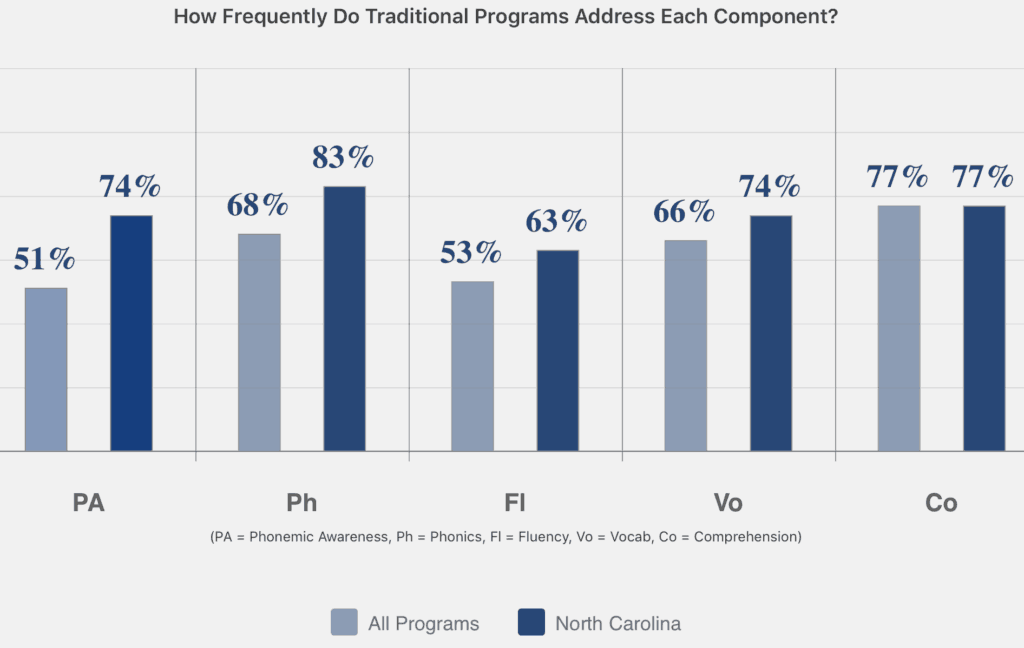

The Teacher Prep Review report is based on a review of the reading coursework and practice opportunities of 1,000 elementary school teaching programs. Analyzing curriculum from undergraduate, graduate, and alternative institutions, NCTQ developed an assessment of where the nation’s educator preparation programs are on teaching future classroom leaders how children learn to read – and specifically the five components of reading.

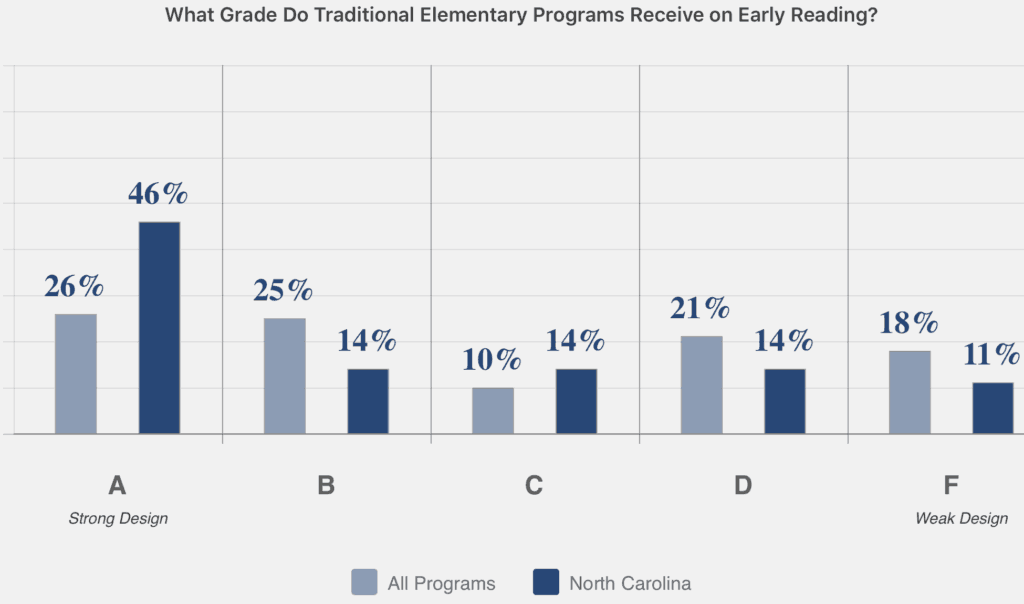

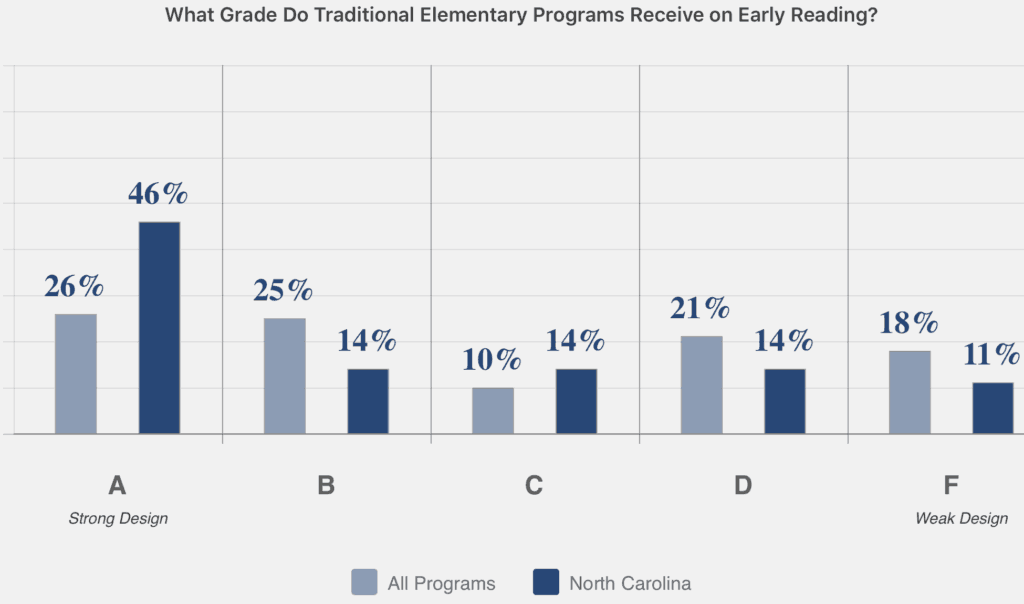

This was the first time since its first report in 2013 that NCTQ focused solely on reading instruction preparation, and it was also the first time that a majority of programs examined received an A or B grade. North Carolina ranked 12th nationally in the report, with 60% of the 35 programs reviewed in the state receiving an A or B grade. In addition to Lenoir-Rhyne, UNC Charlotte received recognition as a “consistently high-performing” undergraduate and graduate institution.

U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos retweeted the report, commenting: “Nearly half of teaching colleges are preparing future educators with what amounts to junk science. No wonder nearly 1/2 of our low-income 8th graders are functionally illiterate. We know how to teach kids how to read. Teachers need the tools to teach it.”

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, the country’s second-largest teachers union, said in a statement that “[t]his good news from NCTQ should strengthen our resolve to use the tools we have to continue to improve reading instruction and to invest in and listen to the educators who are teaching this fundamental life skill.”

The methodology for the Teacher Prep Review is explained in this video. The NCTQ report and the recent national literacy summit for state education chiefs were covered by other news outlets as well.

Coverage from Carolina Journal: https://www.carolinajournal.com/news-article/n-c-doing-well-in-preparing-children-to-read-but-all-the-news-isnt-good/

Coverage from Politico: https://www.politico.com/newsletters/morning-education/2020/01/27/house-to-vote-on-bipartisan-holocaust-education-bill-784690

Article on literacy summit: https://www.the74million.org/article/at-national-literacy-summit-state-education-chiefs-warn-of-reading-stagnation/