As part of National School Choice Week, I had the opportunity last week to visit two separate but distinct places as I sought to cover the choice landscape in North Carolina.

For a recap on the school choice landscape in NC, read this column:

https://www.ednc.org/2019/01/21/school-choice-continues-to-thrive-in-north-carolina/

The EdNC team works to make sure we cover the entire educational landscape. Last week, in addition to the above article and the places I visited in this article, I covered a forum at the John Locke Foundation, Liz covered the Public School Forum’s Eggs and Issues breakfast, Rupen visited a traditional public school focused on Career and Technical Education, Molly wrote this article on charter school policy, and Mebane live tweeted a public education summit by the NC Council of Churches and NCAE. We also published perspectives by Rhonda Dillingham, Justin Parmenter, Terry Stoops, and Keith Poston.

One of the places I visited was an event held by Parents for Educational Freedom in North Carolina (PEFNC) in Wilmington. PEFNC is a school choice advocacy organization, and the event was a celebration of school choice in North Carolina. Later in the week, I went to the Central Park School for Children, a charter school in Durham.

While each place had its own nuances and insights, I came away from both struck by how individual experiences and situations really pave the way for the decisions people make when it comes to school choice.

The highlight of the PEFNC event in Wilmington was a talk by DJ Svoboda. DJ was diagnosed with autism at the age of three and struggled in school, particularly with bullying. His talk was less about school choice and more about how someone who learns differently overcomes his or her struggles. Out of his difficulty, he was inspired to create the Imagifriends of Imagiville, pretend characters in a make-believe world where everyone helps and cares for each other.

See a video of a portion of DJ’s talk below.

His message was particularly on point for the audience, which included Erika Merriman, a co-founder of Oasis NC, a private school specializing in students with autism. Merriman was a teacher in traditional public schools for years but decided to branch out and start her own school when she grew frustrated with what she was able to offer students with special needs. Oasis NC was made possible, in part, by the disabilities grant program.

“It was the answer to our prayers,” she said.

She also was quick to say that she supports traditional public schools, but that there are some students who need a different environment in order to get the attention they deserve.

“It’s not ideal for everyone,” she said. “No school is.”

Former Sen. Michael Lee, R-New Hanover, was also at the event. He was prominent in education when he was in the General Assembly and a supporter of school choice. He lost his seat in the most recent election.

He took the opportunity at the PEFNC event to tell a story he never told when he was in the legislature. It was a story about one of his sons.

“I didn’t do this when I was in public office because it just wasn’t something that I wanted to talk about,” he said.

Lee explained that for the first five or six years of his son’s life, he struggled with medical issues and Lee and his wife were just trying to keep him alive.

“We really weren’t thinking about education at that point,” he said.

But as his son started going to school, education was difficult because of his health issues. Lee said that his son had great opportunities in both traditional public schools and charter schools.

Now, Lee’s son goes to both Alderman Elementary, a traditional public school in New Hanover County, and the Hill School of Wilmington, a private half-day program for students with learning disabilities or attention deficit disorder. Lee said that he and his wife have the means to get their son the attention he needs, but not everybody does. He said he supports school choice so that all parents can have the opportunities that he and his family can afford.

On Thursday, I headed to the Central Park School for Children. It’s a charter school started back in 2003 by Vicky Patton. Patton, her husband, and some friends were on the original board of the Duke School, a private school that focused on project-based education. When that school opened, it was meant to be a model for how education could be done. Principals, superintendents, teachers, and others were invited to come see the innovative approach the school was taking.

Patton said that she would hear skepticism from traditional public school educators. They would tell her that what the Duke School was doing couldn’t be done in a traditional public school. They didn’t have the resources, the engaged parents, or the support.

“I used to always think, ‘I think you could do it in a public school,'” she said.

When the legislature passed charter school legislation, Patton asked some friends if they would help her open a charter school that focused on project-based education, outdoor learning, and other innovative practices. She started trying to get it off the ground in 1999, but it took until 2003 to actually open.

Now the school is an elementary and middle school. Within the school’s charter, the founders wrote that the school exists to promote racial and economic justice in the city of Durham. When the school started, the surrounding area was very poor and affluent citizens of Durham mostly avoided it. Now, it has been transformed by the revitalization of downtown Durham and the gentrification of the surrounding area. Within walking distance of the elementary school is the well-regarded restaurant Geer Street Garden and the popular hang-out spot Fullsteam Brewery.

John Heffernan, director of Central Park School for Children, said he and his staff are acutely aware of the reputation of charter schools when it comes to resegregation. When the school started, it was split pretty evenly between African-American students and white ones. But that changed.

“For us, we recognized 10 years in that we were a mechanism for white flight and class flight,” he said.

The school took active steps to change that, reaching out more to community members and changing its lottery system to give more weight to low-income students.

In the 2012-13 school year, the population of the school was 18.3 percent black, 3.8 percent Hispanic, 1.5 percent Asian, and 71.2 percent white.

After the school’s efforts to promote a diverse student population, in 2017-18 the demographics were 27 percent black, 11 percent Hispanic, 2 percent Asian and 48 percent white. And the school is still working on it.

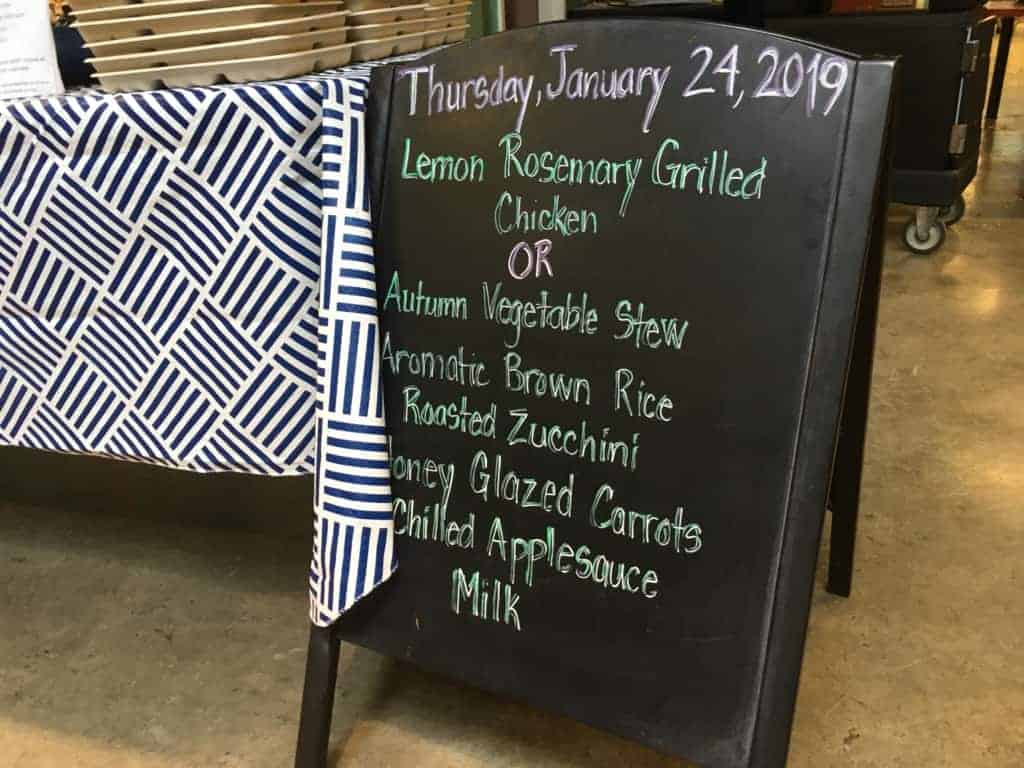

While charter schools aren’t required to provide lunch for students, or free-or reduced-priced lunch for low-income students, Central Park School for Children does all of that. The school brought over the former nutrition director of the Durham Public Schools and its school lunch program has been designated the most innovative lunch program in the country by a group of vegan physicians, Heffernan said.

Central Park School for Children is project-based, and with its focus on economic and racial justice, the students are often working on projects based around the intractable problems that face Durham and the world: things like affordable housing, voting rights, and racial equity.

Everyone I talked to had a personal story of how they came to Central Park School for Children, and it was clear that making the decision to leave the traditional public school system wasn’t one that was taken lightly. But the overarching emotion from teachers at Central Park was one of frustration when it came to traditional public schools and the restrictions put upon teachers by state laws.

“Coming to Central Park was just a whole different experience and opportunity to teach in a way that kids want to learn and not just the way that we’re forcing them to,” said Schara Brooks, an eighth grade science teacher at Central Park who used to work in traditional public schools.

These same frustrations are often echoed in the halls of traditional public schools and the offices of their leaders.

At the end of School Choice Week I was struck, as I always am, at how interesting education in North Carolina is. Debate over things like school choice and how best to fund and create policy for traditional public schools occurs at a high level in the halls of the General Assembly. It is discussed in terms of studies and strategies and politics. But at the ground level, education is always about the experience, and it is always personal to the student, the parent, the teacher, the principal.

Recommended reading