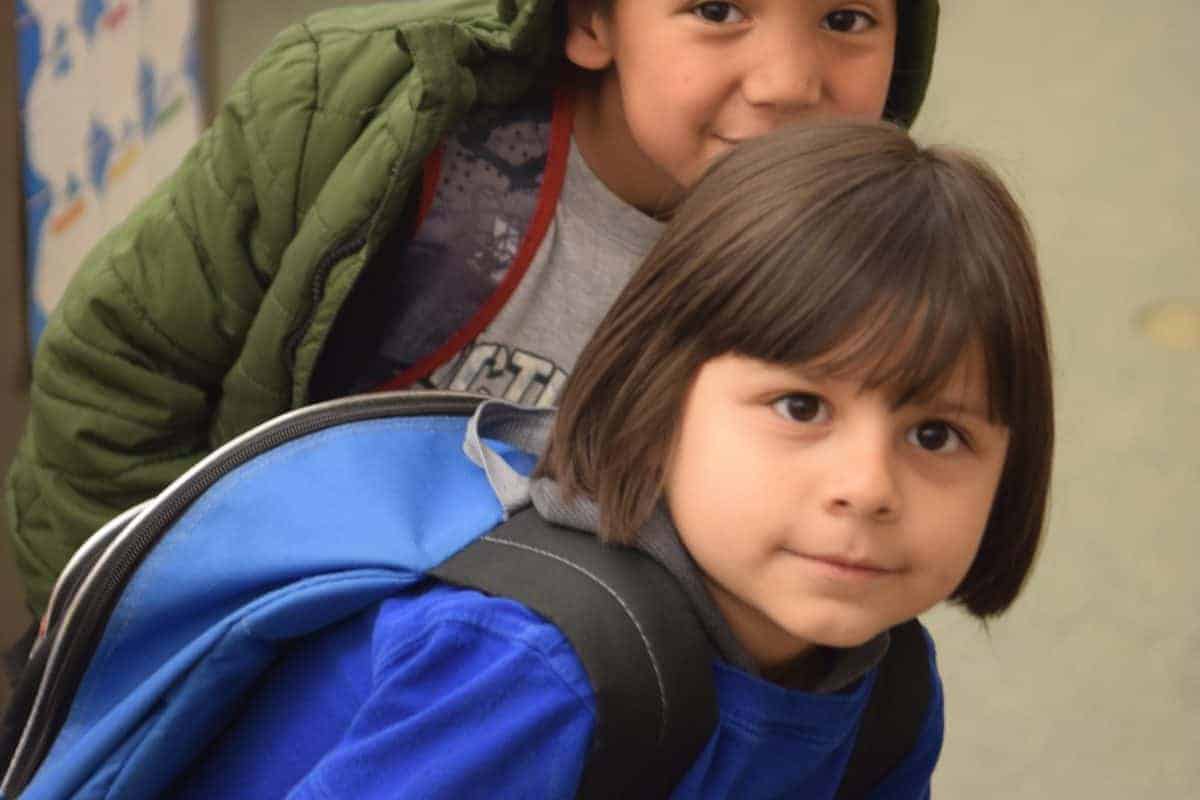

In Swain County, just past a field of elk and a trout stream, on the Qualla boundary, also known as the Cherokee Indian Reservation, the Cherokee have built a silver LEED certified, $124 million, 473,000 square foot school on 14 acres of land. The Cherokee Central School was paid off in 2013, and the bank note was burned in the council house.

This school is tribally operated under a grant from the Bureau of Indian Affairs Department of Education.

Often policymakers on both sides of the aisle debate whether more money for public schools will make a difference. The annual budget of this school, which serves pre-K, elementary, middle, high school, and alternative education students, is $22 million for 1,100 students. Do the math – that’s $20,000 per student each year. Most of the money comes from the federal government, but this casino contributes 2 percent of its revenue each year, and the Cherokee tribe chips in too.

I have never seen a more comprehensive array of facilities and support services at a private, charter, or traditional public school. Attention is paid to the healthy living and healthy spirit of each child.

Healthy living

The elementary, middle, and high schools each have a clinic with a registered nurse (RN) who can dispense medication and provide vaccinations. Each school also offers occupational and physical therapy. Audiology and speech therapy are offered on the campus. The tribal dental program comes to the school, and annually there is a sealant clinic. An asthma specialist is available. There is a program for students with autism. Every class in pre-K to grade three has a teacher assistant, and every grade has an Exceptional Student Services teacher.

The focus on healthy food starts when you walk in the door where a sign announces “No Fast Food Beyond This Point.” The school offers universal breakfast and lunch, and there is no stigma as all kids punch in a code at the end of the lunch line. A central kitchen serves three cafeterias. There are no fryers. Baked sweet potato fries were served the day I visited, and I hear the BBQ is off the hook. That said, the school struggles to get high school students to eat breakfast at all, and they are considering providing breakfast to go in the commons instead.

The focus on native and nutritious foods does not end in the cafeteria. Katie Rainwater with Food Corps is working in the greenhouse, tending to the hydroponic lettuce grown in coconut husks. The school would like to have a salad bar in the high school cafeteria, and they are trying to get GAP (good agricultural practice)-certified so they can use this lettuce there. Raised beds are tended by the gardening club, and blueberry bushes line this entrance to the administrative offices, with beds of ramps up behind the school on the hill. Around the campus, plants like pokeweed are grown with educational signs that teach students if the plant is medicinal, edible, poisonous, or can be used for crafts.

Healthy spirit

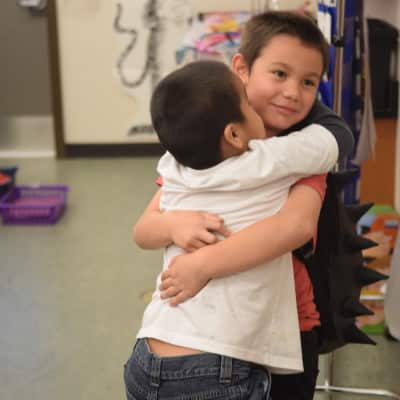

The Cherokee sacred path guides character development in this school for students and teachers. Students are taught to be responsible, truthful, caring, and respectful. Every students represents something sacred on the path, and staff are the keepers of the fire.

Sacred path meetings are held in rooms like this one. In the elementary school, the grades are designated along the sacred path as water beetles, rhythm makers, believers in the little people, basket weavers, peacekeepers, and keepers of the sacred belt.

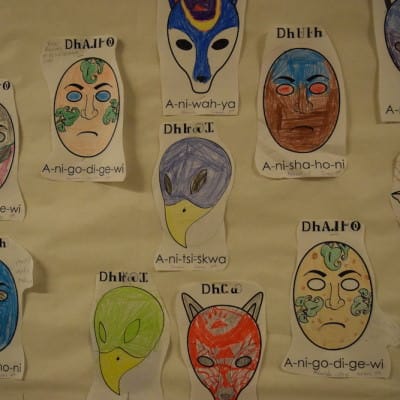

Preserving the culture, including the language and the arts, is a priority. In elementary school, students receive 30 minutes of instruction in the Cherokee language, and in high school, students must take the Cherokee language to graduate. The art program teaches basketry, beadwork, and pottery.

This 350-seat, open air theater in the round has seven sides to represent the seven clans in the Cherokee. These masks adorn the theater, also representing the clans.

The architecture of the school was designed to maximize fresh air and natural light in the classrooms. The chairs are ergonomic.

For these people who have long cared for the earth, it should come as no surprise that environmental considerations also played a role in the design. Cisterns are buried to collect rainwater, and it is used to flush toilets. Solar tubes as often as possible provide lighting, and motion detectors control the lights. All heating and cooling in the offices and classrooms is geothermal.

Fitness is stressed. Each school has its own gym. On the second floor of the field house is a sprinting track. Football, baseball, softball, soccer, and stick ball fields, among others, as well as state-of-the-art playgrounds are scattered throughout the campus. The school has a certified athletic trainer, and it works with Western Carolina University to have interns that work along with the trainer to serve all the athletes.

Our learnings

This school has a lot of money. But it is not an unlimited pot of money, and so they too face tough choices. One that caught my attention was the choice to contract for bus services. The school does not want to own or maintain buses. The Cherokee Boys Club provides the buses for the 24 routes.

The students do not have devices or computers. It is not a 1:1 school.

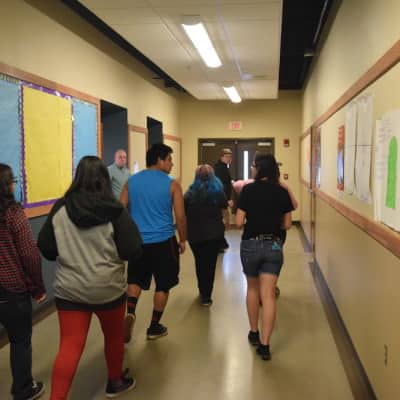

Even with this incredible facility and all the support services, school choice is important. In addition to the Cherokee Central School, families can choose to apply to the Kituwah Tribal Immersion Program, Swain or Jackson Public Schools, or an early college at Southwestern Community College.

Security is intense. Only one door in the whole school is ever unlocked and that is so high school students can get to the cafeteria.

Yona Wade serves as director of the cultural arts center, public relations, and development, and he is our guide. He says he oversees the theaters, an art gallery, a dance studio, and three production rooms. By the end of the day, I realize he really oversees the whole campus. He clearly loves the space and the place.

When I ask Wade about student test scores, he says they are reported to the Bureau of Indian Education, and he describes them as ok. He then notes with pride that relative to the test scores of Native American in other education settings, “We teach Natives better.”