The recent Education Commission for the States’ National Forum on Education Policy in Washington, D.C. brought together policymakers, educators, academics, researchers, and many more in a three-day conversation on education policy in the United States.

A major theme from the conference is the idea that our current education system is not adequately preparing students for the rapidly changing future of work. From the changing nature of work to the changing definition of a “typical” college student, our K-12 and postsecondary education systems are not meeting the needs of students or employers.

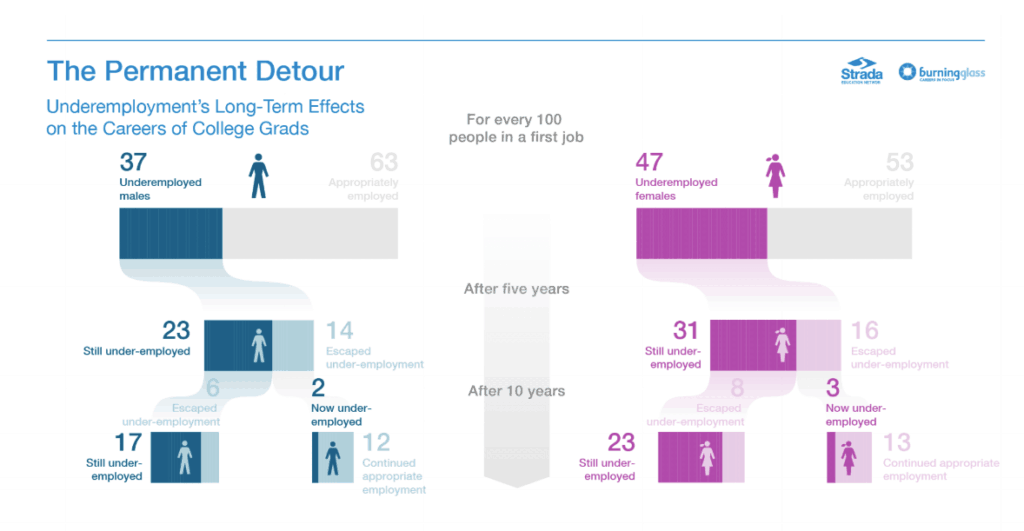

According to Michelle Weise, Chief Innovation Officer at Strada Institute for the Future of Work, 43 of every 100 new college graduates are underemployed in their first job out of college. While it may not seem harmful if a recent college graduate decides to be a barista for a year, it actually is.

College graduates who start off underemployed are five times more likely to remain underemployed in five years and on average earn $10,000 less per year than their appropriately employed peers. Unsurprisingly, it is worse for women than men. One of every three male college graduates starts out underemployed compared to one of every two female college graduates.

Students and employers are recognizing that, for the most part, higher education is not adequately preparing students for the workforce. According to Brandon Busteed, executive director of Education & Workforce Development at Gallup, only 13 percent of Americans strongly agree that college graduates in this country are well prepared for success in the workplace and 11 percent of business leaders strongly agree that graduating students have the skills and competencies their businesses need (Lumina/Gallup 2013 poll).

Yet, Busteed pointed out, colleges and universities think they are doing a good job: 95 percent of chief academic officers rate their institutions as very/somewhat effective at preparing students for the world of work. However, according to the Gallup-Purdue Index, only 27 percent of recent college graduates reported they had a good job upon graduation.

According to Busteed, the highest predictor of educational value and quality is whether or not students feel their courses are relevant to their working experience, and only 28 percent of American workers strongly agree that their coursework is directly relevant to what they do at their jobs.

So what should colleges and universities do? To start, both Weise and Busteed recommend publishing some sort of ratings for institutions based on alumni surveys, but the challenge is much larger.

Weise stated that the first humans to live to 150 years old have already been born. “Are we going to have 100-year work lives?” she asked the audience. “How many jobs that do not exist yet will a person have in a 150-year life? How will two or four years of education upfront prepare us for that?”

The future of work is unknown, but experts have been making predictions about it for years. According to Weise, Deloitte estimated that by 2020, 50 percent of the content in an undergraduate degree will be obsolete. Where does that leave undergraduate institutions?

Many of the presenters believe work and education must be much more integrated in the future. Instead of going for a four-year degree, students will need education at various points in their lives, and institutions must be set up to support them. Right now there are many barriers to that, from the way the federal government gives financial aid to the way classes are scheduled in college.

The typical college student is no longer a four-year student coming right out of high school, and our institutions of higher education have yet to respond to this new reality. These growing numbers of “non-traditional” students combined with the changing nature of work will require institutions to reevaluate their policies or risk losing relevancy in a changing future.