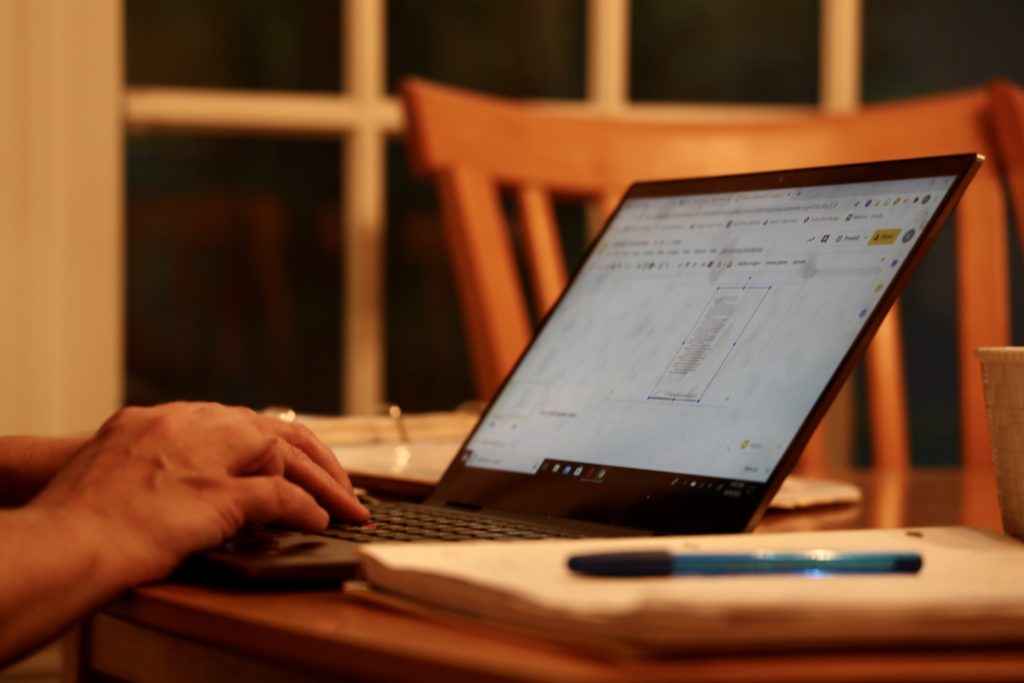

On Aug. 20, the first week of school, at about 6:30 in the morning, Karen Carter was sitting at a table next to a dark window studying her computer screen. The sun hadn’t yet come up, and she was trying to prepare for that day’s class.

Her school was easing into things. She was still trying to resolve technical issues and deal with the fact that not all of her students have gotten their devices yet. Some are still logging on via their phones. The week was about making sure everyone was logging into the right classrooms and had the right codes to participate. The first few weeks are just about orientation, meeting students, getting supplies — that sort of thing.

“After we get through that, we’ll have a better picture of how it’s going to look,” she said.

For Carter, starting up the school year online is a different sort of challenge than it is for other teachers. She is a special education instructional assistant at Davis Drive Middle School, where she is in her ninth year.

It’s possible, she said, that remote learning will actually be good for her students. The kinds of kids she’s working with have most of their classes with the traditional school population. Because of the technology being used, she may actually be able to work with her students more in small groups than she would be able to if this were all happening in the classroom.

Of course, though, she will lose the ability to actually see her students in person, which means that communication is key. If they are struggling, she might not be able to see it. They will have to tell her — something that may be a problem not just for her students but for others across the state.

“There are challenges and trying to think outside the box is a lot of what they’ve been trying to do,” she said. “Our administration team has a lot of good ideas.”

Path to education

Carter came to education sideways. She grew up in Raleigh and graduated from Broughton High School. She attended Meredith College where she graduated with a degree in social work. In fact, she was working as a full-time social worker before she even graduated from college.

When she had her son, she took a break from the workforce. Later, she also had a daughter. But when her two children were both in school, she decided she was ready to go back, and she decided she wanted to do something with kids.

She started as a kindergarten teacher assistant at Davis Drive Elementary School. Due to the make-up of the class she was in, she got some first-hand experience with special education, she said. So when a position opened up at Davis Drive Middle School, she jumped at the opportunity.

She spent her first three years working in a self-contained classroom with autistic students who mostly didn’t have classes with the traditional student population. But she eventually transitioned into her current role.

Advocating for students

Her students are one of the driving forces in Carter’s run for the Wake County Board of Education. One of the most recent press releases from her campaign focused on how special education students are served in Wake County.

The release pointed out that about 12% of the student population in Wake County is made up of special education students and then says that the school board has tried “to minimize their concerns or sweep them under the rug.”

It goes on to list some of those concerns, including transportation, use of physical restraints, lack of training, and more.

Carter said she’s been advocating for years on many different issues before the Wake County School Board, and she has been thinking about running for several years. She finally decided to go for it over the summer.

“We should be here for the students’ best interests, the families. We should all be working together; and all staff, not just teachers, but everybody in the building,” she said.

She said that has become particularly clear in the age of COVID-19, when the risks being assumed by all staff are greater than normal.

The pandemic hits

COVID-19 was a one-two punch for Carter. In addition to working in education, her daughter is still attending Green Hope High School where her son graduated in June. So she had to worry not only about how her students were faring, but also her own child.

In the spring, Carter said her daughter’s live online classes were mostly a time when students could ask questions. Which would be fine, except her daughter isn’t one who is going to ask anything. She’s shy, and given the option, Carter said her daughter likely won’t even have her camera on during an online class.

“It makes it tough,” Carter said. “She’ll just sit there and she’s not gonna ask anything.”

In addition, the grading situation in high school last spring was problematic, Carter said.

Students in ninth through 11th grade were able to take a grade if they wanted to. Or they could get a pass/no credit, based on their grade as of March 13 when in-person instruction ended. Students who weren’t passing by that date could improve to passing via remote learning during the remainder of the semester.

“How do you motivate if you have a good grade that you were happy with March 13?” Carter said. “I think that … was a concern because there wasn’t really any accountability in place. But that wasn’t Wake County, that was the State Board of Education. That so far hasn’t happened this year.”

She also worries about what kind of things students like her daughter might have missed. Her daughter took math last semester, and math builds on itself. When she takes her next math class, will she be ready?

“What happened last spring, it varied by teacher,” Carter said. “It was just hard because expectations all the way around were up in the air and not really consistent.”

Carter’s hope is that the remote learning this year will be more focused.

Wake County Public Schools, where Carter works, was originally going to open in plan B, a mix of remote and in-person instruction, but it shifted to all remote before the school year began.

Carter said she had hoped there would be more options for students and families, but she understands why leaders are making the decisions they’re making.

“Working for the system, I heard both sides with co-workers and I heard both sides from parents and kids, and I think it would be helpful if we could get to a point where there’s enough staff who are willing to go in and work, to let people choose that,” she said.

But she gets that it’s hard to make a decision that leaves everyone happy. And while there are kids who would do better in person, in order to facilitate that, there has to be enough staff comfortable with working in person.

Carter said that she would be one of those who is comfortable going into the classroom. But that doesn’t mean she wouldn’t have reservations. Until that’s an option, she’s just waiting to see how things are going to go.