There were more chronically absent students in North Carolina schools in the 2013-14 school year than would fit in the seats of the football stadiums of UNC-Chapel Hill, Duke University, and N.C. State University — combined.

Amy Jablonski, the Department of Public Instruction’s director of integrated academic and behavior systems, explained the root causes of chronic absenteeism and why it is attention-worthy to the State Board of Education Wednesday. According to the Office of Civil Rights, 207,837 students missed more than 15 days in the 2013-14. The figure represents about 14 percent of North Carolina students.

Thirty-six states, plus Washington D.C., incorporated chronic absenteeism, which includes unexcused and excused absences, as a measure of success in their Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) plans to the U.S. Department of Education. Several board members were disappointed North Carolina’s plan, submitted in September, did not mention the factor. The General Assembly mandated the contents of the plan.

During the board’s bi-annual planning and work session Wednesday, board member Olivia Oxendine said she hoped to learn from the states who did put an emphasis on the issue.

“I think the value of having chronic absenteeism in a plan such as ESSA is that it will force attention on the issue,” Oxendine said. “Number two, out of it must come some very good interventions that I hope that we can learn from.”

Jablonski shared results from studies showing the effects chronic absenteeism has on student achievement. A study from Baltimore in 2012 found chronically absent students in pre-K and kindergarten were both more likely to be absent later in their lives and have lower achievement levels. A 2008 study found chronically absent kindergartners had lower academic performance in first grade, with double the impact if the student came from a low-income family.

Middle schoolers who are chronically absent are more likely to fail classes in high school, according to a 2014 study in Chicago. A 2007 study, also from Chicago, showed attendance among ninth graders was the strongest indicator of how well those students did in courses — and course performance was the strongest indicator of graduation.

Though chronic absenteeism matters in ninth grade, Jablonski said the issue starts way before then.

“It does get concerning when the belief is that this is a high school problem,” Jablonski said.

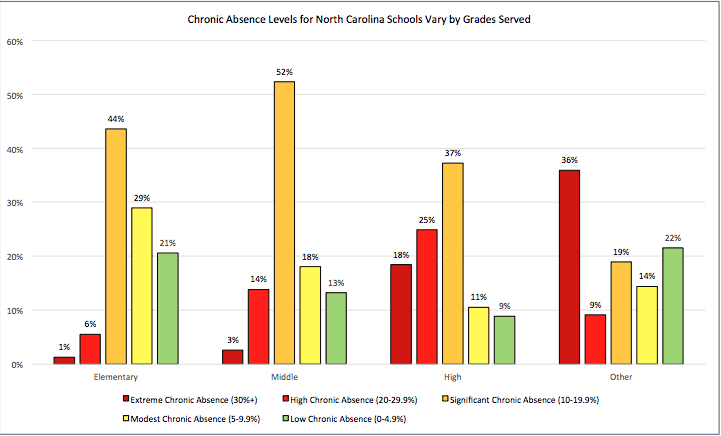

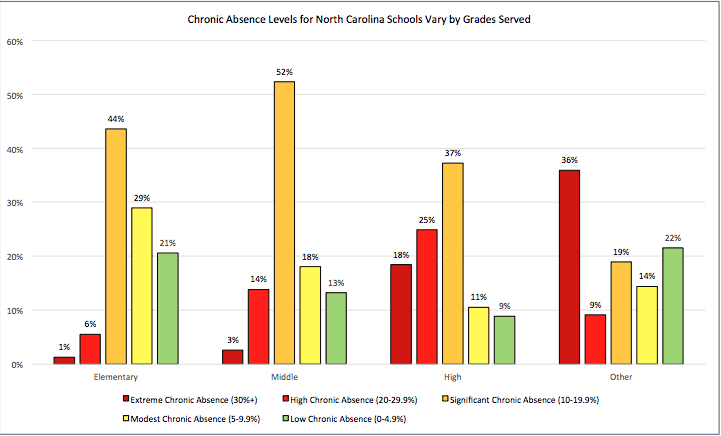

The following chart from Jablonski’s presentation shows levels of chronic absenteeism in North Carolina elementary, middle, and high school students from 2013-14.

Jablonski said the earlier schools act, the better.

“Really, it’s an elementary issue,” she said. “Students who are chronically absent in pre-K are chronically absent throughout their life … so it is about early intervention.”

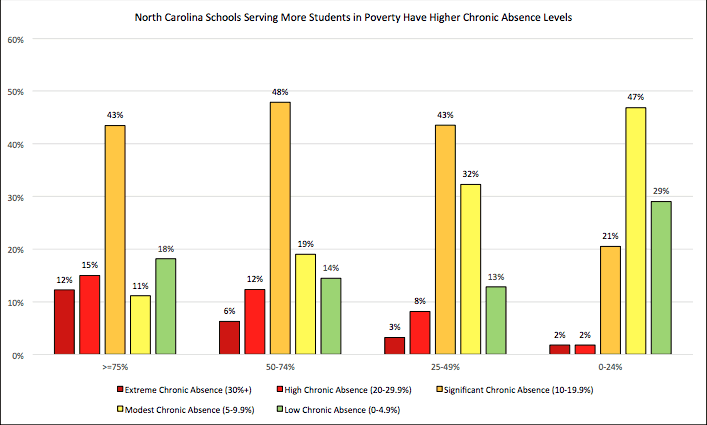

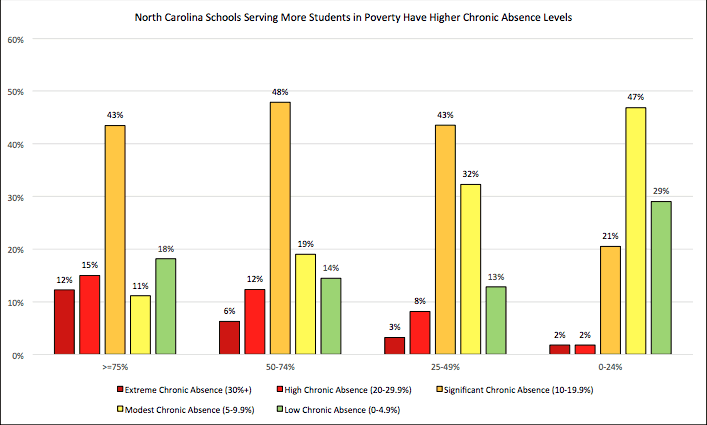

Chronic absenteeism does correlate with poverty, Jablonski said. The following chart displays the trend, with the same data from 2013-14. According to Jablonski’s presentation, minority students are also more likely to be chronically absent.

Jablonski said attendance levels seem to some to not be something teachers or schools can change.

“There is this myth that (chronic absenteeism) is not actionable,” she said.

She shared a national study out of Frloida that interviewed 667 chronically-absent middle and high school students, asking why they were missing school. The two biggest reasons were both things, Jablonski emphasized, that can be improved: health and transportation.

“Addressing chronic absenteeism will have a positive domino impact,” she said.

Board member Patricia Willoughby said she related the core issue of chronic absenteeism to so many other issues discussed by the board in their bi-annual meeting.

“If we address this, we’re addressing a root rather than a symptom,” Willoughby said.

Board member Amy White said having community partners to relay the message to low-income families is important.

“For the folks in this room, it is common sense,” White said. “But for families who are repeating the cycle of poverty, it’s not. And so, we need more communicators. DPI, teachers, principals, administrators would naturally assume that responsibility, but we need more partners at the table to help communicate the importance of time spent in school and long-term results.” White added that medical providers, who see students the most outside of the classroom, could be a great help.

Jablonski said the state’s Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) program is at work in schools by noticing early indicators and using data-based solutions to intervene when a student has a problem. She said the state needs to come up with a common definition of chronic absenteeism and improve data collection of attendance rates.

Willoughby said external factors affecting student attendance and performance needs an approach that considers students’ complex needs.

“I think that’s where the whole child model comes in,” she said. “You know we’ve got to address why students aren’t there…”

In November 2016, the board adopted the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model, which looks at the school building as a hub for different kinds of services for children and promotes relationships between school systems and community and health organizations.

Pilot programs in three districts — Hoke County, Iredell-Statesville, and Halifax — are implementing the model and shared their progress with the board Wednesday.

Hoke

Hoke County Schools took a systemic approach in implementing the “whole child” model.

“We became very intentional about our planning process,” said Superintendent Freddie Williamson, who sits on the state board a superintendent advisor. His staff added that the district wanted the approach to be ingrained in everything they did, and sustainable no matter who is in charge.

Hoke County Schools developed common language to talk about the external factors facing their students. They determined financial needs to fund the work. They made sure their decisions were driven by data and collaboration. They set clear goals.

Over the last year, countless programs and partnerships with community organizations have formed. They send backpacks full of food home with students who do not have reliable meals outside of school. They have also started a summer feeding program to address students’ nutrition deficiencies during summer break. After-school programs and a “Saturday school” were also established. They partnered with the local fire station to help with their needs, and trained high schoolers to be volunteer firefighters.

A member of Hoke County Schools staff said they’ve tried to make their leadership stop saying, “We shouldn’t have to do this,” and instead ask, “Why wouldn’t we?”

Iredell-Statesville

Superintendent Brady Johnson expressed excitement about the progress the Iredell-Statesville district has made since adopting the “whole child” approach. He said the district’s first step was a survey to gauge 1,700 students’ realities.

“This was a wake-up call for our community,” Johnson said. He said students were reporting that they were engaging in “risky behavior” and had serious mental health issues.

From there, Johnson said he was able to use the results to get different sectors of the community at the table.

“It really leveraged our ability to sit down with all of our community members and engage in a very serious conversation about … what kind of community do we really want to be?” he said. “And what do we want for our children? This has brought in partners that we didn’t even know existed.”

He said more than 150 faith-based institutions stepped up to partner with the district, as well as health departments, non-profit organizations, and business leaders. He said some businesses shared that they have hundreds of unfilled positions because candidates are unable to pass drug tests.

Johnson is thankful for this new approach but was clear that the district has a long way to go. In the past 18 months, he said, the district has had three students commit suicide.

“I do think we’re at a crisis point,” he said.

Halifax

Halifax County Schools started several initiatives over the last year of looking at its work through the “whole child” lens.

“Throughout the course of last year, we started talking about the well-being of all of our students and staff,” Superintendent Eric Cunningham said. “That’s probably our number one core value, taking care of each other.”

Cunningham said the district changed its mission statement to include the “whole child” model to ensure the work continues well into the future. The first partnership they made was with Goodwill after Cunningham and his staff realized students were coming to school wearing dirty clothes. He installed washers and dryers in every Halifax school.

“A clean child is a happier child,” he said.

The district went on to provide dental screenings for students through the Duke Endowment, rebranded one high school to focus on meaningful certifications for students to graduate high school workforce-ready, and started cultivating a seven-acre farm to promote healthy eating and create jobs within the community.

Each school also added a “chill out room,” where students getting off the bus in the morning, or as-needed throughout the day, can go to take a nap or exercise on a Wii Fit. He said these partnerships and strategies are necessary in addressing students’ needs.

“…The barriers that we have are real to us, and we are responsible for creating solutions with you to respond to the needs of our whole child,” he said.