State Sen. Fletcher Hartsell has introduced legislation, Senate Bill 463, that points North Carolina forward. The bill contains two simple sentences:

“(A)n individual who (i) has attended school in North Carolina for at least three consecutive years immediately prior to graduation and (ii) has received a high school diploma from a school within North Carolina or has obtained a general education diploma (GED) issued in North Carolina shall be accorded resident tuition status …. This act is effective when it becomes law.”

If enacted, the legislation would make thousands of unauthorized immigrant young people living in North Carolina and currently in the state’s public schools eligible for in-state tuition at public universities and community colleges. Under existing state law, students who arrived in the United States without documentation must pay much higher out-of-state tuition.

If enacted, the legislation would make thousands of unauthorized immigrant young people living in North Carolina and currently in the state’s public schools eligible for in-state tuition at public universities and community colleges.

The bill has been referred to the Committee on Rules and Operations of the Senate, whose chair is state Sen. Tom Apodaca. In the 2003-04 legislative cycle, Apodaca co-sponsored a nearly identical bill — the only difference is that the previous bill required four years of attendance rather than three years prior to high school graduation.

Hartsell is a Republican who represents Cabarrus and Union counties, both in the Charlotte metro region. Hispanics constitute nearly 10 percent of the 192,000 residents of Cabarrus, and 11 percent of the 218,000 residents of Union. Apodaca is a Republican who represents Buncombe (6 percent Hispanic), Henderson (9.8 percent), and Transylvania (3 percent). Several Democratic lawmakers joined in sponsoring both the 2003-04 legislation and the current bill.

A profile of North Carolina’s “unauthorized population,” published recently by the Migration Policy Institute, estimates that the state’s schools now have 34,000 students without legal immigrant status.

The Hartsell bill, in effect, calls on legislators to face up to the reality that North Carolina has transitioned from a biracial to a multi-ethnic state. And that transition confronts the state with the twin education challenges of dealing with the legacy of racial division and of raising the achievement of Hispanic young people.

Closing such gaps would give North Carolina a stronger workforce and civil society.

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, 47 percent of white North Carolina 8th graders scored proficient or above on the NAEP test in math, Hispanic 8th graders 27 percent; whites 43 percent in reading, Hispanics 23 percent. Closing such gaps would give North Carolina a stronger workforce and civil society.

Of course, the “browning” of North Carolina is no longer breaking news. The population of Hispanics grew from 76,000 in 1990 to more than 845,000 today — growth of 400 percent in the 1990s and 111 percent in the 2000s. As a result of the Great Recession, immigration, especially from Mexico, has slowed.

On her demography blog, Rebecca Tippett of the Carolina Population Center reports, “Just over half (53%) of North Carolina Hispanics were born in the United States or a U.S. territory; 47% were foreign-born. Examining the top birth places reveals two main locations: Mexico and North Carolina. Nearly 270,000 or 32% of North Carolina’s Hispanics were born in Mexico. Another 260,000 or 31% were born in North Carolina.”

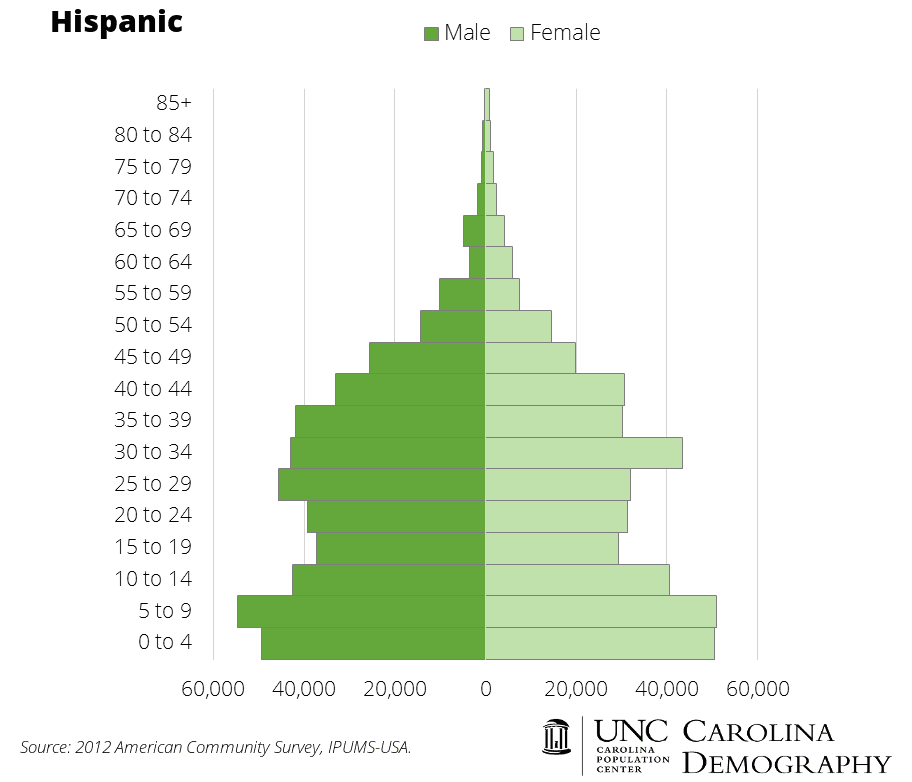

Tippett’s blog has an illuminating graphic that forecasts further Hispanic population growth – and how North Carolina’s future depends on educating Hispanic young people.

NC Hispanic Population by Age and Sex, 2012 ACS

“The age structure of the Hispanic population is a classic population pyramid: large population sizes at younger ages taper to very small population sizes at older ages,” Tippett writes. “Unlike the state’s non-Hispanic population, children ages 5-9 comprised the largest age group among the Hispanic population (nearly 106,000). Children ages 0 to 4 were the second largest Hispanic age group, with 99,920 individuals. Together, nearly 1 of every 4 Hispanic residents in North Carolina was under the age of 10 in 2012. In contrast, fewer than 75,000 Hispanic residents were age 50 or older.”

An in-state tuition bill is not the only response required to these demographic dynamics. For example, the state would have to stem the upward creep of tuition at the campuses of the University of North Carolina system, which may well discourage young Hispanics who would see a university education as out of reach financially, even at lower in-state rates.

But, if enacted, the Hartsell legislation could have important ripple effects — not the least of which is to send a signal to high schools, to both Hispanic students and their teachers, that a postsecondary education is not out of reach. In the economy of today and the near future, education beyond high school is a practical necessity for employment that assures a middle-class standard of living.

While state policy has required undocumented Hispanics to pay out-of-state tuition, some philanthropic efforts have sought to make postsecondary education more affordable for Latinos.

While state policy has required undocumented Hispanics to pay out-of-state tuition, some philanthropic efforts have sought to make postsecondary education more affordable for Latinos. The North Carolina Society of Hispanic Professionals has a college fund that awards financial aid of $500 to $2,500. The Tomorrow Fund for Hispanic Students has awarded $560,000 in scholarships since 2010.

“Our preference is toward undocumented students,” said Diane Evia-Lanevi, founder of the Tomorrow Fund. “Our goal is to see these kids through to graduation.”

The Hartsell legislation gives the General Assembly an opportunity to lower the barriers to community college or university graduation for Hispanic young people whose educational attainment will help determine North Carolina’s future.

Recommended reading